Mirror magic with Mobilux

Following up my post about BBC Television’s 1952 experiment in abstract art, I came across a fascinating piece about the special effects system that, in its earliest form, was the inspiration of the programme. When the BBC producer Christian Simpson first met John Hoppé in 1952, the latter’s technique for projecting abstract moving images lacked a name. But less than a decade later, as a September 1960 article in Popular Mechanics shows, the process was called Mobilux and it was being used for special effects in American television. The image above is a detail from one of the photographs accompanying the piece (reproduced below); the caption reads:

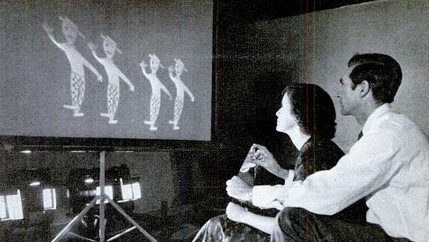

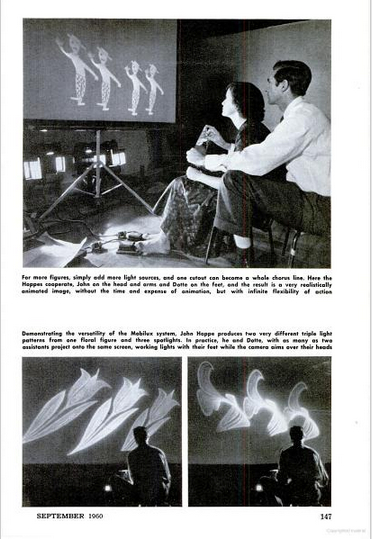

Here the Hoppes co-operate, John on the head and arms, Dotte on the feet, and the result is a very realistically animated image, without the time and expense of animation, but with infinite flexibility of action.

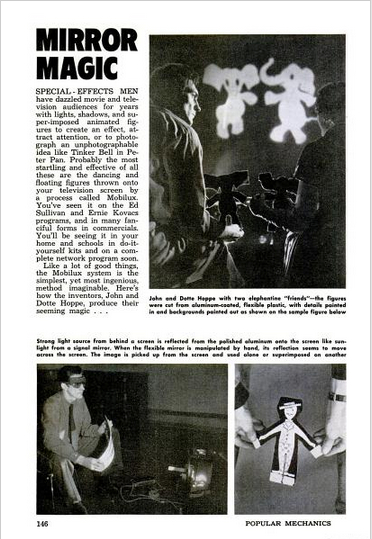

John Hoppe (the acute accent has gone) had clearly been busy since his encounter with Christian Simpson, for the article says that Mobilux has been used ‘on the Ed Sullivan and Ernie Kovacs shows, and in many fanciful forms in commercials.’ (For more on Ernie Kovacs, see Frank Bren’s excellent piece for Bright Lights Film Journal, November 2011.)

The explanation for how Mobilux works is as follows:

Strong light source from behind a screen is reflected is reflected onto the screen like sunlight from a signal mirror. The image is picked up from the screen and used alone or superimposed on another.

The article promises that ‘you’ll be seeing [Mobilux] in your home and schools in do-it-yourself kits and in a complete network program soon.’

A piece in the Herald Statesman from Yonkers, New York, published on 6 March 1957, fills in some of the background. Talking to reporter Steven Scheuer, Hoppe acknowledges that his system – which he calls ‘lumia, or color music’ – has been around for a couple of centuries:

I developed the instruments I now use on television from instruments used in the original lumia process. The first one was an instrument using candles, which was built in 1751. As far back as 1895 there was an instrument which mixed light from an organ keyboard. In 1925 there was a flurry of interest in lumia, and there were many performances of it. It was very pretty but it was used without music and died down.’

John Hoppe also developed Mobilux in a fine arts context and his artwork ‘Mobilux Suspended Projection’ was included in 1967 in the exhibition Lights in Orbit at the leading New York gallery run by Howard Wise. Two years later, Wise organised the landmark show TV as a Creative Medium which is regarded as the first American gallery exhibition of artists video (although Hoppe was not part of this).

In 1957 Hoppe outlined to Steven Scheuer a grand vision for the future of his lumia techniques:

I’m excited about this process and I don’t think there are many limits on it. This is the art of vision, the way music is the art of sound. I think in due time networks will have ensembles of lumia the way they now have ensembles of musicians.

But that was not to foresee first video technology and then digital effects, both of which demonstrated that anything that Mobilux could do they could do far better.

There is clearly more to research here – and I would be delighted if anyone has additional details to contribute to the tale – but for the moment here is a brief example from 1960 of how – long before CGI – Mobilux was used on American television to create animated graphics – in this case the endorsement ‘A dazzling delight – Winchell’.

John,

I don’t know about Mobilux, but I know a little about lumia, or colour music. The 1751 (approx) instrument was supposedly developed by a Jesuit priest Louis-Bernard Castel, the Clavecin Oculaire, which tried to mix the seven colours of the spectrum (using candles) to an irregular musical scale. No working model seems to have been demonstrated.

The 1895 concert with a ‘colour organ’ (as you played the instrument coloured lighting was generated on a screen) was given by A. Wallace Rimington, a great advocate of combining music and colour. It took place in London at St James’s Hall, 6 June 1895, and he wrote a paper on it which is reproduced in a special issue on colour of the journal Living Pictures (vol no no 2, 2003) which I edited.

Rimington wrote a booklet, Colour-Music: The Art of Mobile Colour in 1911 – there’s a copy on the Internet Archive – https://archive.org/details/colouartof00rimi.

Classical music composer who wrote synesthesic pieces combining music and colour include Schoenberg and Scriabin, whose Prometheus (1911) calls for use of the colour organ.

After Rimington, the leading British advocate of the form was Adrian Klein (aka Adrian Cornell-Clyne) who wrote the fabulous Colour-Music: The Art of Light (1926). Klein produced his own Klein Colour Projector. He went on to be a leading writer on colour cinematography and producer of the Dufaycolor film process. Other advocates in the 1920s were Mary Hallock Greenewalt and Thomas Wilfred (who named his version of the colour organ the Clavilux).

It’s a rich history, which ends up spectacularly if often bathetically with lights shows at rock concerts. It’s really interesting to learn that TV was in on the act too.