OTD in early British television: 4 February 1938

John Wyver writes: What is arguably the origin moment of one the simplest and most obvious television techniques occurred in a broadcast talk on the evening of 4 February 1938.

The esteemed art historian R.H. Wilenski was reviewing the mammoth exhibition of seventeenth-century European visual art on show at the Royal Academy. He was speaking with reproductions of key paintings in the studio, and producer Mary Adams conceived the idea of moving a camera across one of the photographs. What three decades and more later rostrum camera maestro Ken Morse would do every working hour, Adams appears to have invented on the spot.

Fragile priceless canvases could for the most part not make the journey up to Alexandra Palace, and so for the earliest talks about old master paintings large monochrome reproductions were employed. In November 1937 National Portrait Gallery assistant keeper John Steegman spoke about family likenesses in portraits of the House of Stuart. As a frustrated, anonymous contributor to The Listener reflected,

The method of showing us the portraits was to place them before the camera so that the head or the head-and-shoulders under discussion filled the whole screen… It would perhaps help add interest to television talks of this nature if the producer were… to show us a close-up view of any particular section of an illustration as it comes under discussion.

Three months later, in a Listener review of Wilenski’s talk, the writer ‘G.G.W.’ noted that in this case the viewer was first shown pictures full-frame, and then the detail that was being discussed. The writer continued:

In the case of [Jacques] Callot’s ‘Procession of Gypsies’, a long strip thirty-one inches by twelve, the camera was focussed on one end of the picture and then moved along, giving the effect of pulling the painting across the screen. It was effective because in this particular painting the method of inspection from left to right is precisely what the viewer would have been likely to adopt if he had had the original in front of him.

Obvious, perhaps, to us today, but the Emitron cameras were fairly inflexible, and even when mounted on dollies they could primarily move in and out. Perhaps one of the cameras was mounted laterally on a truck on this occasion. In any case Adams and the operator that night clearly managed to make it work, and so opened up a whole new approach to animating, and indeed narrativising, paintings on screen.

The very particular extended dimensions of the Callot canvas, of course, encouraged this, in a way that a conventional full-length portrait would not have done. So perhaps we should think of this early sixteenth-century artist as a co-creator of rostrum camerawork.

(Of course, Adams may well have been using this technique before this broadcast, but this is the first account of it that I have found, and clearly the writer felt that it was sufficiently novel to detail it.)

Wilenski had set out to be a painter, but finding success elusive, he became a critic and lecturer in art history, at the time of the broadcast attached to the University of Manchester. He published extensively, and again when this programme was made, he was probably best known for The Modern Movement in Art (1927) and The Meaning of Modern Sculpture (1932).

He had appeared on television once before this broadcast about the RA show, in a programme in early December 1937. For that transmission, which was also produced by Mary Adams, he provided a commentary on the different approaches to drawing a bowl of fruit by three artists with him in the studio: Iain MacNab, John Skeaping and the French cubist Amédée Ozenfant.

The Royal Academy show was a blockbuster exhibition with over one thousand exhibits, the majority of them paintings, but with a range of other works as well. Thanks to the RA today, both the catalogue of the show (original price 1/6) and also an illustrated souvenir (5 shillings) are available online. Both are fascinating documents.

In the introduction to the catalogue, the RA president William Llewellyn, himself a distinguished portraitist, wrote:

For the winter months of 1938 the Roval Academy has made the experiment of holding an Exhibition illustrating the development of art in the several countries of Europe during a single historic period- the Seventeenth Century. by means of works selected from collections in this country.

With the gracious support of Their Majesties The King and Queen, and the generous assistance of institutions, trustees and private owners, the Committee have succeeded in assembling a display of paintings, drawings, sculpture, tapestry, furniture, silver and other works of art which provides a unique opportunity of studying and assessing the achievements of artists in this period.

Notable examples of the painting of Rubens, Van Dyck, Rembrandt, Vermeer, Velazquez, Murillo, Claude and Poussin are among the major attractions of the Exhibition; but it also contains a large number of excellent works by less known painters which will surely increase and clarify the general reputations of these artists.

All of which was well worth a 20-minute talk on the fledgling television service.

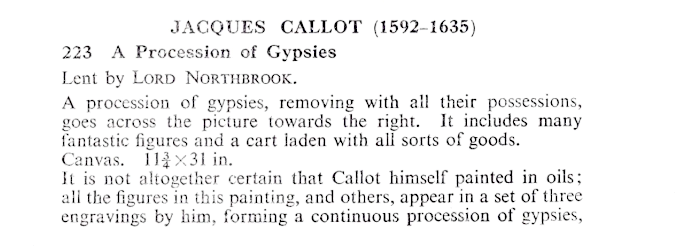

As for the work of art treated by Mary Adams in the manner singled out by the writer, ‘A Procession of Gypsies’ by Jacques Callot was listed in the catalogue in this way:

Not exactly in the exalted company of Rubens, Van Dyck, Rembrandt and the like, Callot was far better known as an engraver and print-maker than as a painter, with Wikipedia noting that he was

an important person in the development of the old master print. He made more than 1,400 etchings that chronicled the life of his period, featuring soldiers, clowns, drunkards, Romani, beggars, as well as court life. He also etched many religious and military images, and many prints featured extensive landscapes in their background.

Intriguingly, in the catalogue the canvas is listed as ‘Lent by Lord Northbrook’, whereas online now it apparently belongs to the National Museum in Warsaw. Is it possible that two versions exist, or did Lord Northbrook put it up for sale at some point, when the Polish museum acquired it?

Header image: ‘Gypsies on the Road’ (detail) by Jacques Callot (1592-1635), National Museum in Warsaw; the full painting is reproduced in the body of the blog post.

Leave a Reply