Magic Rays of Light: from the Introduction

John Wyver writes: Tonight in the Reuben Library at BFI Southbank, I am in conversation with BFI Television Curator Lisa Kerrigan talking about, of course, Magic Rays of Light: The Early Years of British Television, which was published on Thursday. There are still a few tickets left.

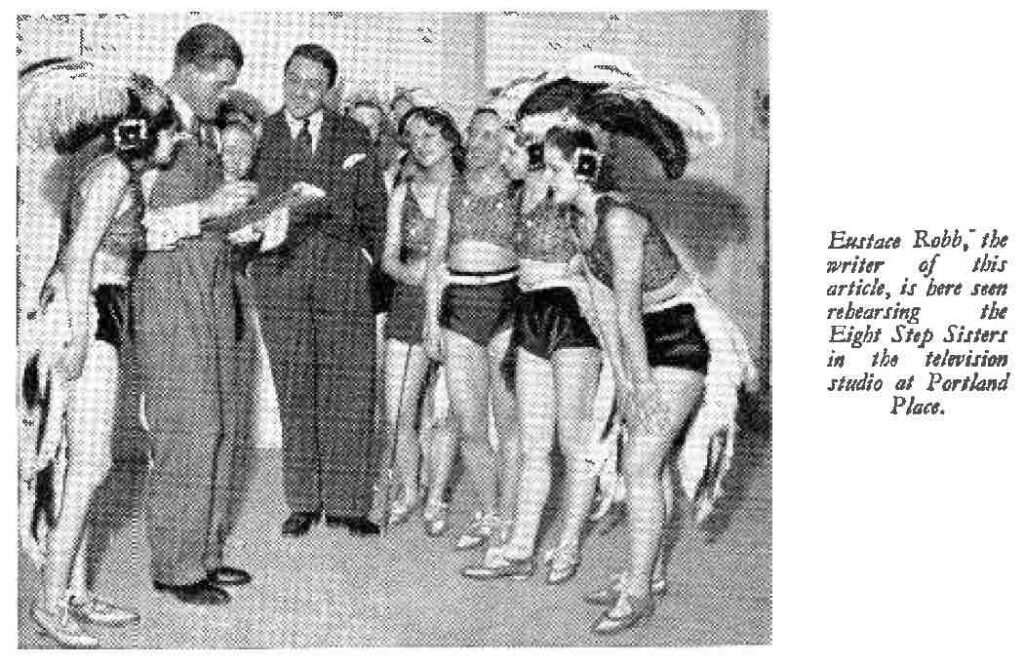

In all of the blog posts I have been contributing about this, I have not yet shared the central arguments of the book, and it is these that I outline here in this extract from the Introduction. Also briefly noted are two of the key characters in the book, critic Grace Wyndham Goldie and 30-line producer Eustace Robb (above). I spend most of the time on the book’s first proposition, and will return to the other four in future posts.

One of the central figures in this story is critic and later producer Grace Wyndham Goldie, who contributed thoughtful television reviews to The Listener between 1937 and 1939. This perceptive writer will appear frequently here, but for the moment permit me to adapt a phrase that she penned about the start of television drama. In my amended form, this runs, ‘If being in at the birth of television isn’t exciting, I don’t know what is.’

To capture and convey that excitement, Magic Rays of Light is structured by five expansive propositions, the first of which is that television between the wars in Britain was extensive, rich, complex and innovative.

Television at its beginnings, the book further submits, was intimately entangled with the cinema, theatre, variety, music, dance and visual arts of the time.

My third thesis is that television in these years responded to and now reveals key aspects of interwar social histories, embracing legacies of the Great War, changing gender roles for women, qualities of suburban living and more.

Early television in Britain, as the book also details, took a wide variety of forms, which were often different from those familiar from post-war domestic broadcasting.

And finally, Magic Rays of Light demonstrates that, despite the near-total absence of recordings, television in its first years can nonetheless be explored in detail as a cultural form.

When the BBC’s 405-line television service shut down just after noon on 1 September 1939, two days before Neville Chamberlain declared that Britain was at war with Germany, there had been almost daily transmissions from AP since late August three years previously.

Broadcasts starting at 11am (of a ‘demonstration’ film, repeated daily), and then for between 60 and 120 minutes from 3pm and 9pm each on most days (although not initially on Sundays) had radiated thousands of hours of variety, comedy, features, talks, plays, music, opera, dance, newsreels and more.

There had been productions of numerous classic plays as well as stagings of romantic comedies and whodunits, the first soap opera and the first sitcom. Appearances by leading singers and soloists, comedians and magicians complemented ambitious presentations of grand opera, classical ballet and modern dance.

Talks evolved into feature programmes along with tentative attempts to develop television ‘documentaries’. Much of this had been radiated from AP’s two small studios, which were equipped with electronic cameras, but complex ‘outside’ broadcasts (OBs) had also been mounted from across London and the suburbs.

And by experimenting constantly, failing frequently, and innovating intensively, producers had effectively invented much of the screen language and many of the programme forms that remain recognisable today.

The 34 months of the official service, along with several weeks of test transmissions, had followed on from the far-less-well-known broadcasts of 30-line television. These began with the Baird company in November 1928 and continued under BBC control, four or five times each week, from August 1932 to September 1935.

With low-resolution, mechanically-scanned images and initially very basic technical capabilities, this television saw the introduction of camera movement, shot changes and graphics, and was as significant for the future of the medium as the service that followed from AP.

Dismissed by later practitioners and largely ignored by commentators, these transmissions brought to the screen a remarkable range of collaborators, among them variety stars including Gracie Fields, Josephine Baker and Nina Mae McKinney, and most especially many of the luminaries of contemporary ballet, such as Alicia Markova [below, in the Studio BB at Broadcasting House] and Lydia Sokolova.

30-line television also staged the first television talks, art displays, narrative features, dramas, and outside broadcasts. Crucially too, the basic grammar of television emerged in these first transmissions, quickly coalescing into a distinct aesthetics.

The low-fi, portrait-format images of singers and dancers, to the extent that we can reconstruct them, now appear strange and uncanny, and yet they can be seen as echoed, faintly perhaps, by today’s Tik-Tok and Instagram short-form videos.

The first major creative figure in this story who had primary responsibility for the BBC’s 30-line broadcasts is Eustace Robb, Britain’s second television producer (after the even more obscure Harold Bradly). Eton-educated and Sandhurst-trained, Robb served in the Coldstream Guards after the First World War, and throughout the 1920s was a swell lauded in society gossip columns.

After joining the BBC to take up the television post, he drove the 30-line service, expanding its offerings, extending its artistic possibilities, and attracting a stellar line-up of guests. Then in 1935, early in the planning of the 405-line service, Robb was passed over for the director of television position, and his employment was eventually terminated in March the following year.

This pioneer is barely remembered today, and yet he deserves recognition as one of the major forces in securing the extent and ambition of British television.

Header image: Eustace Robb and the Eight Step Sisters, from Television, June 1934.

Leave a Reply