Centenary day

John Wyver writes: Happy 100th birthday, television! Exactly one hundred years ago tonight, John Logie Baird gave the first public presentation of what he called ‘true television’ in his workshop about what is now Bar Italia at 22 Frith Street, London. This blog starts with an extract from Magic Rays of Light: The Early Years of Television in Britain, following which are some links to other online elements marking today.

from Magic Rays of Light:

A wretched nonentity working with soap boxes in a garret’ is how in his memoirs John Logie Baird wryly characterised the way he believed the world regarded him at the start of 1926. After attempting to manufacture diamonds, and selling Borax-infused undersocks, the would-be entrepreneur had started three years before experimenting with a system for seeing by wireless.

Thirty-five and sickly, he tinkered with his television apparatus in his Hastings bedroom and in July 1923 filed a first patent. Eighteen months later he set up his ‘garret’ workspace in London’s Soho, with research continuing on shoe-string funding as he sought to introduce his apparatus to a sceptical world. Baird’s fortunes began to change, however, when with a new business partner, soap distributor Oliver Hutchinson, he arranged a public demonstration on Tuesday 26 January 1926.

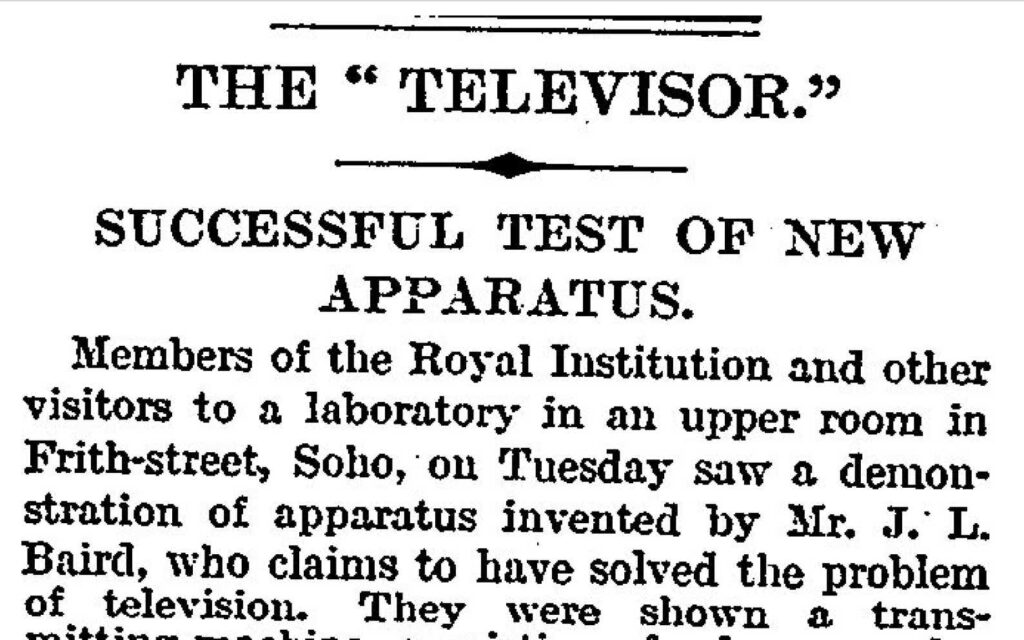

Invited guests, many of them members of the Royal Institution and their partners in evening dress, climbed the three flights of narrow stone stairs at 22 Frith Street. After waiting in a draughty corridor, they were ushered six at a time into the inventor’s tiny rooms. Among the witnesses was a Times correspondent, whose three-paragraph story (above) was relegated to two-thirds of the way down a page 9 column.

Visitors ‘were shown a transmitting machine,’ the journalist recounted, ‘consisting of a large wooden revolving disc containing lenses, behind which was a revolving shutter and a light sensitive cell.’ Rather more colourfully, Baird recalled that the disc was ‘a most dangerous device, had they known it, liable to burst any minute and hop round the room with showers of broken glass.’

After a sketchy explanation of the workings, The Times’ prosaic first draft of history continued:

First on a receiver in the same room as the transmitter and then on a portable receiver in another room, the visitors were shown recognizable reception of the movements of the dummy head [the puppet “Stooky Bill”] and of a person speaking.

What was already called ‘looking-in’ involved peering along a cardboard tube, at the end of which could be seen, as another journalist detailed, ‘features [that] came out as rather blurred black lines in an orange light… the change of expression from opening the mouth to smiling and putting out the tongue could be seen.’ A hand, a pipe and a notebook being flicked through were similarly recognisable.

These images just about fulfilled Baird’s definition of ‘true television’, being ‘transmission of an object with all gradations of light, shade and detail so that it is seen on the receiving screen as it appears to the eye of an actual observer.’

As the inventor later noted, somewhat hopefully, ‘The audience were for the most part men of vision and realised in these tiny, flickering images they were witnessing the birth of a great industry.’ And as Donald McLean wrote,

The 1926 demonstration was a pivotal event in Baird’s life, marking the transition from his existence as a poor garret-flat inventor to global recognition for achieving television, and coming at a time of strong social interest in new media communications as the public acceptance of radio broadcasting matured.

A century ago, John Logie Baird achieved a landmark moment in television history. The viewers weren’t convinced

This is Don McLean’s very fine, complementary account, just published at The Conversation.

John L. Baird’s (private) television demonstration on January 8, 1926, as seen by the British press

And this is an essential collection of contemporary newspaper articles, assembled by André Lang at his wonderful History of Television (and some other media) website.

Leave a Reply