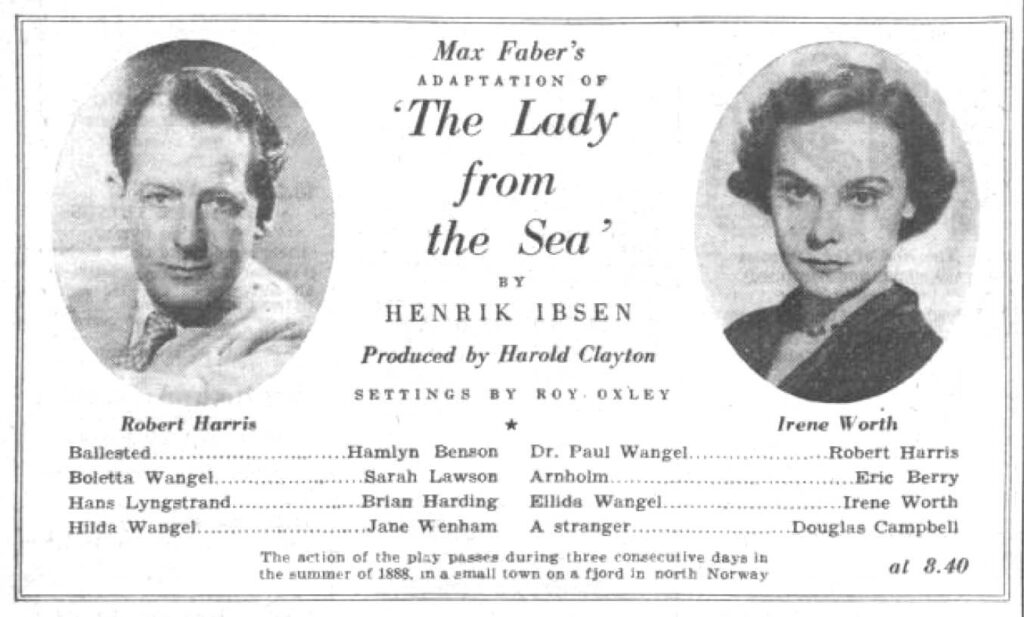

BBC Ibsen 2: The Lady from the Sea, 1953

John Wyver writes: The earliest programme to be featured in BBC iPlayer’s treasure trove of Henrik Ibsen plays and documentaries is the production of The Lady from the Sea, first shown in May 1953. Seen initially in the days just before the Coronation of Queen Elizabeth, this is one of the very earliest television dramas to be preserved in the archives, and as a consequence is a recording of singular interest. It is a bonus that it also remains a highly watchable, engrossing and indeed moving production.

The text used, which as far as I can tell is a very full one, is an adaptation by the prolific Ibsen translator Max Faber, and it comes over as robust and in no sense archaic. The detailed studio settings by Roy Oxley (who a year later would provide the face of ‘Big Brother’ in the BBC’s production of Nineteen Eighty-Four) have a somewhat constrained, theatrical feel, featuring the garden and conservatory of the Wangel family, a mountainside seat, and a fishing pond, all set before backdrops with rather obviously painted mountains.

This recording, made as was the case before the introduction of videotape by 35mm filming of a screen on which the live electronic image was being shown, is almost certainly of the second transmission. Union agreements stipulated that only the second showing could be preserved, so ensuring that a record could not be played again to deny work to the cast. Moreover, at least two reviews of the Sunday showing complain that it was plagued by studio “noises off”, while no such problems are apparent here.

The focus of the production, as it must be for this Ibsen drama that is the closest he came to writing a Chekovian comedy, is the performance of Ellida, here played vividly and vitally by the wonderful, fearless Irene Worth. The live broadcast, played twice, first on the evening of Sunday 10 May 1953, and then the following Thursday, must have been just days before she flew to Stratford, Ontario, to take part in Tyrone Guthrie’s first Festival season there.

Thirty-six years old at the time of transmission, Nebraska-born Irene Worth had made her Broadway debut a decade earlier, before moving to London to work in 1951 with Guthrie at the Old Vic, where she took the roles of Desdemona, Helena, Portia and Lady Macbeth. Later, she worked extensively with Peter Brook, playing Goneril to Paul Scofield’s Lear in the director’s landmark staging and subsequent film, and also in his experimental Orghast in Paris and Iran.

I first wrote about this production for the Screen Plays blog some 14 years ago, when I hymned Irene Worth’s performance in these terms:

She is by turns elated (with her wet hair flying free), deeply troubled, strong, touching, passionate, grand, vulnerable and loving, both towards Paul and – finally – to his daughters.

The remaining cast are somewhat overshadowed by Worth, although Robert Harris, another Old Vic and Shakespeare Memorial Theatre stalwart, gives a more-than-decent Wangel, and on this viewing I was very taken with Sarah Lawrence as Wangel’s elder daughter, Boletta.

Ibsen’s play is a study of freedom, duty and responsibility, with frameworks of medecine and artistic creation, and skeins of dreamworlds and the supernatural threaded through its watery world and its language of the sea and storms and drowning and ice. And as Peter Black, writing for the Daily Mail, recognised, this play, like other Ibsens, was ideally suited to television:

Not for nothing does TV drama regard Ibsen as one of its three most valuable mines of material [after Shakespeare and Shaw, presumably?] He proves every time that in television drama the most important thing is the word, built into a dramatic construiction as unbreakable as granite and used with artistic economy.

The screen language

Perhaps the greatest interest of this production, however, derives from it being one of the very first records that we have of television’s language for studio drama. Producer Harold Clayton, who had overseen an admired A Doll’s House the previous November, choreographed his cameras with clarity and precision, and as Listener critic Philip Hope-Wallace recognised there was ‘never a cut in the wrong place, never a point missed.’

The range of shots is narrow, with only the introductory move across the garden set feeling expansive, and with images otherwise restricted to tight groupings of at the very most five characters, to mid-shots for conversations between two figures, and to occasional tighter singles as the drama intensifies. The presentation is also consistently frontal, with the actors speaking out to the camera, or making a strong point if they are turned away.

Most of the action is confined to one plane, and there is little use (perhaps because of the constraints of the studio) of staging in depth. Nor is there any use of classical shot-reverse shot dialogue sequences, as are standard in films, but which live multi-camera production prohibits [but see correction in Comments]. The screen world is presented directly, almost tableau-like, rather than being assembled through editing. And the standard use of flat, even, mostly overhead lighting offers next-to-no opportunities for subtle shading or modelling of faces and figures.

In addition to the sweeping shot that begins the play, there is some but restrained use of camera movement, including modest reframings to underscore a dramatic point. And shots are held for far longer than we expect in drama today. (I have not attempted to calculate an average shot length for the production, but that would be a valueable research exercise.)

There is also a powerful quality of stillness to the whole, which is especially effective at the moment (pictured below) when Ellida first senses the arrival of the stranger, her former lover, who has returned across the sea to take her away. Is it fanciful to see here a composition resonating with the paintings of Ibsen’s compatriot Edvard Munch?

Learning to look again at studio drama

All of which may suggest that this production, as with other studio drama from the next three decades, is a dull watch, lacking in visual distinction, and that it can be dismissed as ‘theatrical’. Yet to do so, misses the particular pleasures of this form, which I am ever more convinced we need to learn to look at once more.

We need to look at studio drama in its own terms, to appreciate its pleasures and potential, to understand it as an aesthetic form in itself, and not simply dismiss it as an inferior version of classical filmmaking.

I sometimes think that we are at a point, forty years on from the shutting down of studio drama, that is comparable to, say, the 1960s and the attitudes of the time towards silent cinema. To generalise wildly, pre-1930s filmmaking was understood by all but a handful of committed specialists, as unrealised version of cinema, of historical interest at best.

Since then, scholars and general audiences have increasingly embraced silent cinema, appreciating its marvels, and enjoying and coming to understand it without thinking of it largely as a way-station towards the realised superiority of an essential cinema aligned with later classical Hollywood.

Learning to look without prejudice at studio productions like The Lady from the Sea, along with many of the other Ibsens in this collection, is important for us now. As is the study of the production context of work like this, of the technologies with which they were created, of the working practices and understandings of the casts and crews, of the ideas about aesthetics held by producers and by audiences, and of so much more.

And finally, a note on the online print

Given how that this was originally a tele-recording from a screen, and that it dates from more than 70 years ago, the visual and sound quality seems to me little short of miraculous. Clearly, the master has gone through a digital restoration that has removed almost all sense of the lines of the electronic image, and while there is occasional instability in the image and some damage is apparent, especially in Act IV, this is never intrusive.

What the digital process has done, I think, is to introduce a softening of the image, so that it has a ‘painterly’ quality that is appropriately atmospheric, and indeed arguably like pictorialist photography of the late nineteenth century. The soundtrack is also remarkably clear, and the inclusion of optional subtitles is an excellent enhancement.

The restoration and availability of this version is a cultural event that should be attracting attention and admiration. As I wrote in the first of these Ibsen columns, I’m honestly bemused as to why the BBC hasn’t been making more of a fuss about this, even if only in the form of a press release and a special, perhaps BFI-partnered big-screen outing.

On Bluesky, Andrew Orton offered this important correc tion:

“Lovely! Though I’d take issue with, ‘Nor is there any use of classical shot-reverse shot dialogue sequences, as are standard in films, but which live multi-camera production prohibits.’ and insist suggest that it’s something that more or less every studio drama produced after this did regularly.”

To which I replied as follows:

You’re right, of course – daft mistake. What I meant to say was something closer to shot-reverse shot sequences were challenging to create with the inflexible cameras and studio configurations of the time. I’ll add a Comments note to the page. Many thanks!