Magic Rays at BFI: Elstree Follies

John Wyver writes: The final screening in the BFI Southbank season linked to the publication of Magic Rays of Light: The Early Years of Television in Britain is on Saturday afternoon at 15.00. The oddball programme pairs Elstree Calling, 1930, with the astonishingly eccentric and super-rare Television Follies, 1933. Tickets are still available, and you can book here. Below I’m reproducing the programme note that I have compiled for the event, which provides further details about both films.

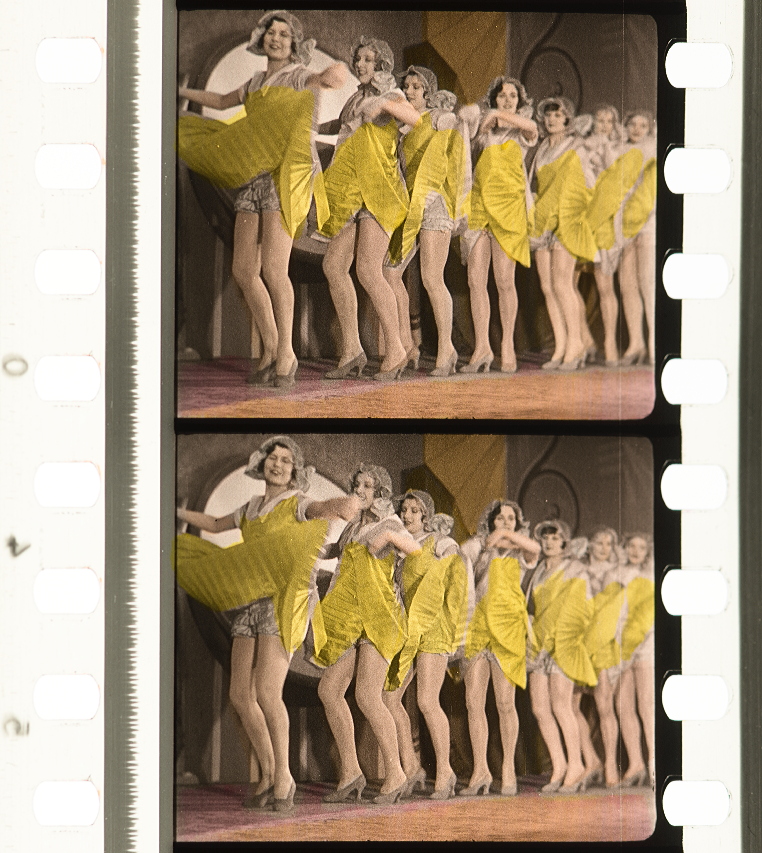

Television Follies, 1933

Produced by Geoffrey Benstead’s Manchester-based production company English Films Ltd, Television Follies appears to have initially gone into production under the title of Chinese Nights, and this change begins to make sense of some of its bizarre yet fascinating qualities.

From the summer of 1932 the BBC was operating a 30-line television service from Broadcasting House, having taken over the project from Baird Television Ltd. Late-night transmissions were scheduled roughly three times a week for around 30 minutes on each occasion.

Television Follies must have been released to exploit the interest in this new technological mavel. But as ‘H.H.H.’ wrote in The Era (5 July 1933), ‘This is not a serious attempt to exploit the televisor; here it is just a means to introduce vaudeville turns. This is not the best effort of Geoffrey Benstead. His direction here lacks any attempt at originality.’

In the family scenes Baird ‘Televisor’ receiving set is sitting on the table next to a radio, which would have been necessary because the audio was broadcast separately (on another wavelength) from the picture. The 9×3 portrait screen of the Televisor occupies the right-hand third of the machine, and the shot of the family jostling to get a look at the screen feels like a realistic depiction of such a viewing situation.

The cut at around five minutes in, which supposedly takes the viewer to the image on the screen, is absurd, as are all the purportedly ’television’ images. There is far more detail, camera movement, and setting in all these scenes than would have been feasible to transmit in 1933.

None of the vaudeville scenes, apart from the ‘Scottish’ songs, make any attempt to replicate what a television image of the time would have looked like. The switch then to the oriental(ist) scene is simply weird, and the assumption must be that these sequence were shot for Chinese Nights. Presumably that project was abandoned, and these were shoe-horned into this television-framed variety bill.

At the end the vaudeville strand invades the space of the family, replacing the Televisor as the source of entertainment. It’s almost as if the film wants to demonstrate that vaudeville and film is superior, more involving and more authentic than television. Indeed by the time of the boy soprano, television is entirely forgotten, and traditional entertainment that re-unites the family (earlier set to squabbling by the Televisor) has seen off the competitor that threatened to invade the domestic space.

Elstree Calling, 1930

The Baird Television Development Company began experimental 30-line television transmissions in November 1928. These semi-regular late-night presentations of mostly variety and music hall artists, complemented by occasional talks and even a the first television drama, Box and Cox, in December, prompted a wave of press interest in the new medium.

And this in turn, despite few people having actually seen television in action, led to imagined uses of the medium appearing in various forms in a clutch of British feature films made at the turn of the decade. One of these, Elstree Calling (1930), which was produced for John Maxwell’s British International Pictures, is an oddball intermedial melange. Primarily the responsibility of director Adrian Brunel, it also features ‘sketches and other interpolated items’ by Alfred Hitchcock.

Elstree Calling hedges its bets about television, and in common with later features, recognises the emerging medium as a potential threat to cinema’s dominance. As a consequence, it sets out, even as it exploits television’s fashionability, to trivialise it.

Promoted as ‘A Cine-Radio Revue’, the film is essentially a string of variety acts, many of which came from Jack Hulbert’s current West End revue The House That Jack Built. Between the numbers, compère Tommy Handley introduces the performers as if they were being televised into homes. The ‘camera’ is a plain box on a wooden frame, with no operator in sight.

Threaded around Handley’s spots and the acts are six very brief comic scenes featuring Gordon Harker trying to fix his domestic television set. Working with a hammer and chisel, he succeeds only as the ‘transmission’ comes to a close, suggesting that cinema is more reliable than the newer medium and less dangerous, since his receiver explodes at one point.

Elstree Calling includes four sequences shot in crude Dufaycolor, but the screen grammar used to film the acts, with one central camera for a master wide and two offering tighter shots on angles from either side, is close to the standard language that would be employed in the BBC’s television studios at Alexandra Palace after November 1936.

Excerpted from Magic Rays of Light: The Early Years of Television in Britain by John Wyver, available in the BFI Southbank bookshop

The question of what Hitchcock actually did on this production […] remains one of the most obscure issues in his career. What is beyond dispute is that Adrian Brunel planned and shot most of the film but was removed from it at a late stage by BIP management, who then called upon Hitchcock for some repair work.

To interviewers, Hitchcock routinely dismissed his contribution as being brief, marginal, and (speaking to Truffaut) ‘of no interest whatsoever,’ giving no details and thus allowing commentators a free hand to assess where his input might be detected. […]

There are three main elements in the film that critics have attributed to Hitchcock. The first is a series of brief scenes in which a “ham” (Gordon Harker) tries to pick up, on his primitive home receiver, pictures of the show that is being transmitted from Elstree in vision as well as sound; he manages to find brief glimpses of the compère (Tommy Handley) but nothing of the show itself. […]

The second element is ‘The Wrong Flat’ (the title used in publicity posters), the film’s most self-contained sketch and the only section of it, apart from the framing scenes with Harker, not to have a theatrical setting. Again, scene time is brief, less than two minutes.. […]

Third is a strand in which another Hitchcock player, Donald Calthrop (Blackmail, and subsequently Murder! and Number Seventeen), has a more sustained role, as an actor determined to insert some Shakespeare into the revue. After popping up a few times and being snubbed, he eventually succeeds with a recitation of lines from Hamlet and Henry V – simultaneously performing magic tricks in order to sugar the cultural pill.

Excerpted from Hitchcock Lost and Found: The Forgotten Films by Alan Kerzoncuf and Charles Barr (University Press of Kentucky, 2015)

Leave a Reply