Mañana, the backstory

John Wyver writes: Late on Sunday night, BBC Four brought to the screen the 1956 BBC production of Arthur Benjamin’s 75-minute opera Mañana. The transmission was 70 years to the day after its television premiere, and the recording is now available for the next 29 days on BBC iPlayer. The resurrection of this from the archives is remarkable, just as is the current availability of the 1953 The Lady from the Sea, and one can only hope it suggests that the schedulers will continue to burrow into the available riches.

Frustratingly (and I’m tempted to add, of course) there is no detailed information available on iPlayer, and not even a still, while on transmission there was only a spare line of presentation voice-over noting the anniversary.

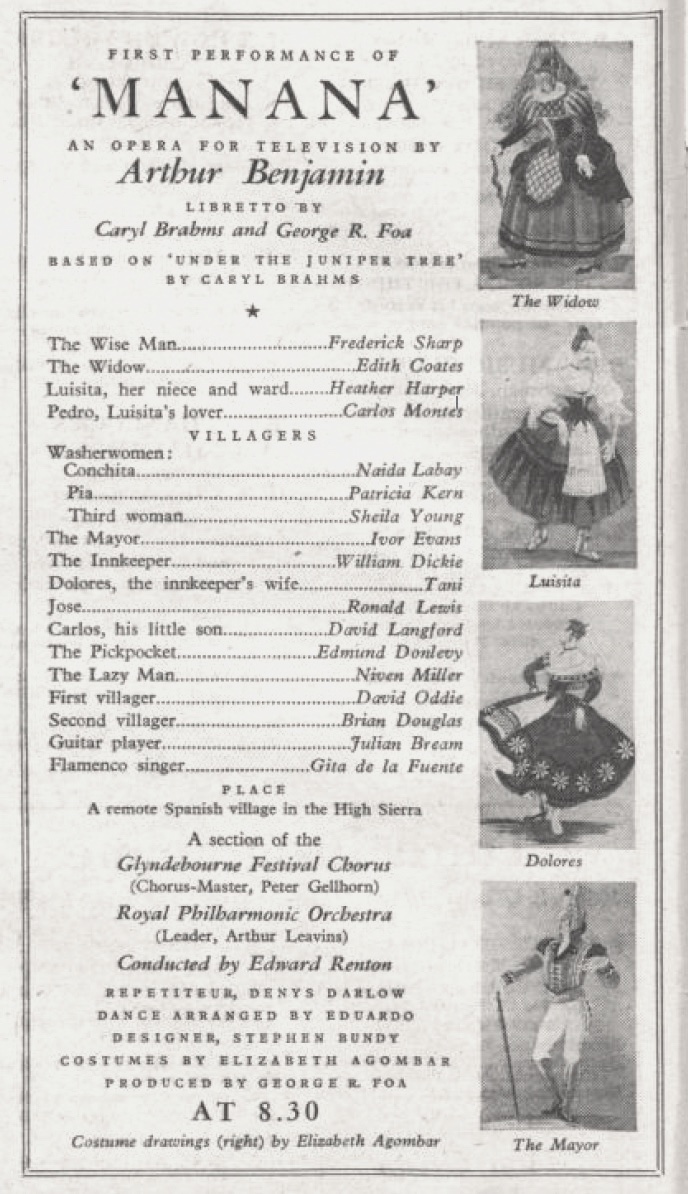

So ahead of thoughts about the production in a post later this week, today I’m sharing something of the backstory to the opera’s production gleaned from Radio Times and other online sources. The drawing above accompanied a feature in the Radio Times issue of 27 January 1956, when the production graced the magazine’s cover.

The composer

Born in Australia in 1893, Arthur Benjamin came to London to study at the Royal College of Music. He served in both the infantry and the Royal Flying Corps in the First World War, spending the final months of the conflict in an internment camp after his aircraft was shot down.

In the post-war years he taught piano at the RCM to many notable performers and composers, including Benjamin Britten. During the Second World War he was teaching in Canada, and he performed, taught and broadcast there, as well in the United States, through the late 1940s and much of the 1950s. He died in 1960 in a London hospital.

In addition to a wide variety of orchestral and chamber works, and the popular novelty Jamaican Rumba, composed in 1938 after a visit to the West Indies, Benjamin wrote five operas, including A Tale of Two Cities, 1950, first performed during the Festival of Britain, and Tartuffe, after Molière, which was unfinished at his death.

He was also a prolific composer of film music, including scores for the Alexander Korda production of The Scarlet Pimpernel, 1934, and Alfred Hitchcock’s The Man who Knew Too Much, 1934. Post-war, his work included Korda’s film of An Ideal Husband, 1947, and the epic documentary The Conquest of Everest, 1953.

For Grove Music Online, Peter J. Pirie wrote,

With the exception of several works his music is jovial in mood and uncomplicated in technique; a touch of neo-classicism in the Violin Concerto (1932) merely reflects the compatibility of the manner with Benjamin’s essential cheerfulness.

The commission

In the United States in 1951 NBC commissioned the first opera conceived initially for television, the one-act wotk Amahl and the Night Visitors from Gian Carlo Menotti. Its live broadcast as the first programme in the Hallmark Hall of Fame series was seen as a critical success. Amahl… was then produced by Christian Simpson for the BBC on 20 December 1953, and the reception was so positive it was repeated live (that is, mounted again) on Christmas Eve 1954. A further presentation followed in 1955.

The enthusiasm for this work must have been a factor (although further archival research is needed to confirm this) in the BBC deciding in 1955 to make a first opera commission for television in Britain. An obvious composer choice would have been Benjamin Britten, whose Gloriana had been a less than total qualified success in 1953, but who the following year had premiered the enthusiastically received The Turn of the Screw.

Might awareness in musical circles of Britten’s homosexuality been a factor in him being passed over? Or would it take another decade before the composer was sufficiently intrigued by the medium to write Owen Wingrave especially for television. For whatever reason, and perhaps because of his balance of ‘lightness’ and cultural credibility, the choice fell on Arthur Benjamin.

According to producer George R. Foa, writing in Radio Times, Benjamin read Caryl Brahms’ short story ‘Under the Juniper Tree’ soon after receiving the commission, and knew immediately that it was the right subject. Brahms studied piano at the Royal Academy of Music in the 1920s, where Benjamin would likely have been her tutor. But recognising her shortcomings as a performer, she left without graduating and became a ballet, and later theatre, critic.

A writer also of comic stories, she published the thriller A Bullet in the Ballet, co-written with S.J. Simon, in 1937, and three further novels featuring Inspector Adam Quill followed. The year before A Bullet…, she edited a volume from a symposium, Footnotes to the Ballet, and during the war she wrote a study of the dancer and choreographer Robert Helpmann.

In the 1960s she established a writing partnership with Ned Sherrin, and together they contributed to That Was the Week That Was, as well as co-authoring a string of adaptations for theatre and television, including a series of Feydeau farces, broadcast between 1968 and 1973 as Oh-La-La!

The libretto for Mañana is credited to Brahms and producer George F. Foa, who recalled about the writing process,

In a comparatively short time the story had dispensed with some of its original characters, admitted a few newcomers, acquired new situations, and Mañana was born.

The producer

George R Foa contributed to a number of musical broadcasts during the war, but his first television credit appears to be as producer of a proggramme with the Italian baritone Tito Gobbi in March 1950. Later that year he adapted and produced a studio version of Pergolesi’s comic opera La Serva Padrona, and then Puccini’s Madam Butterfly in two parts in October. Other music programmes followed before Puccini’s La Bohème in September 1951 and Verdi’s Rigoletto in February 1952.

By this point he was clearly the BBC’s go-to guy for studio opera, and there were productions of Gounod, Humperdink, Mozart, Rossini, Bizet, Donizetti and Smetana. He also devised and produced the series Opera for Everybody (1953-55) which was presented by Huw Wheldon.

(As the list of composers suggests, the BBC by this point had established a very strong tradition of studio opera. For pre-war opera productions, see my Magic Rays of Light: The Early Years of Television in Britain, pp. 210-13.)

Approaching Mañana Foa wrote that

It became evident from the beginning that to transform this story into a television opera a new system had to be devised: first of all we had to build the village, drawn on blue-print within the compass of the television studio — the patio of the inn, the widow’s house, the smithy, the gaol, the washing-trough, the Wiseman’s cave, the maze of streets leading to the shrine.

Then the village map was re-arranged to house cameras and microphones at vantage points, and dummy characters were used to work out action and continuity in every single detail.

The designer was Stephen Bundy, who from 1947 on had created settings for a range of BBC variety shows and dramas, as well as George Foa’s 1954 studio production of Puccini’s The Girl of the Golden West.

Only when the studio plan was fully worked out was the libretto written.

At this point in our collaboration Caryl Brahms… found that she had to learn an entirely new technique, using uncomplicated syllables with open vowels to suit the singers, simple words with simple sentences which, like well-behaved children, never draw attention to themselves.

Reflecting of his work with Benjamin, Foa wrote,

Arthur Benjamin is a master of the orchestra; his previous operas… show that he is also a master of the theatre; especially his Tale of Two Cities… With Mañana I think he has completely succeeded in transforming the man of the stage into a man of the screen — he has packcd into just over an hour

True to his theatrical principles, he has not written a single aria for the sake of its melody, but only when the situation demanded it-yet all his music is mclodious and easy on

the ear.

The cast

Composer and producer attracted a very strong cast, with most notable name seventy years on being the soprano Heather Harper as Luisita, even though she had made her professional debut the previous year as Lady Macbeth in Verdi’s Macbeth for the Oxford University Opera Club. In 1956 she sang Violetta in George Foa’s BBC studio production of La traviata, and from this point on was strongly associated with Benjamin Britten’s works.

Baritone Frederick Sharp as the Mayor had already sung roles for Britten in The Rape of Lucretia and Albert Herring, and he went on to be a regular for Sadler’s Wells Opera. Edith Coates (The Widow) had established herself as Sadler’s Wells’ principle mezzo-soprano before the war, and for the company she had created the role of Auntie in the landmark production in June 1945 of Britten’s Peter Grimes.

As to what all of this talent actually achieved in Mañana, you will have to wait for my thoughts, and my gleanings from contemporary critics, in a further post this week.

Leave a Reply