A new adventure

John Wyver writes: With Magic Rays of Light: The Early Years of Television in Britain still with the printers, and on course for publication by Bloomsbury on 8 January, my thoughts have turned to new projects.

I have a couple of spin-off ideas from that research, but I am more or less certain that my next substantial book will be a complementary volume, tentatively titled Switching On, exploring the cultural history of television from the war to the first night of ITV in September 1955. My aim is to have that published for the 75th anniversary of the commercial network on 22 September 2030.

I have started to dip into research for this, and one of the paths that I want to follow is that of television beyond broadcasting. One strand of this will consider the Rank Organisation’s commitment in the late 1940s to ‘cinema television’, the projection of live electronic images in picture houses. And another is the post-war development of television by the military, most especially the RAF.

A particularly intriguing area to dig into is what scholars have begun to call ‘useful television’. The Amsterdam Institute of Humanities Research is a partner in a standing seminar series on this topic, organized by Markus Stauff and Anne-Katrin Weber, working with the definition of

television’s application as a useful tool, rather than a mass medium. The examples range from military and industrial applications of television technology to its operational use in medicine, science, or sports.

We partly build on older debates in film studies (e.g. non-theatrical cinema; useful film) and want to bring television into this debate. Looking at useful television requires to broaden and to complicate our understanding of what media do and how they do it. Additionally, it contributes to an alternative genealogy of ‘digital media’.

A particularly interesting example that I have come across recently is the installation four years after the end of the war of a closed circuit television system at Guy’s Hospital. Maurice Gorham in his 1949 book Television: Medium of the Future has a detailed footnote about this:

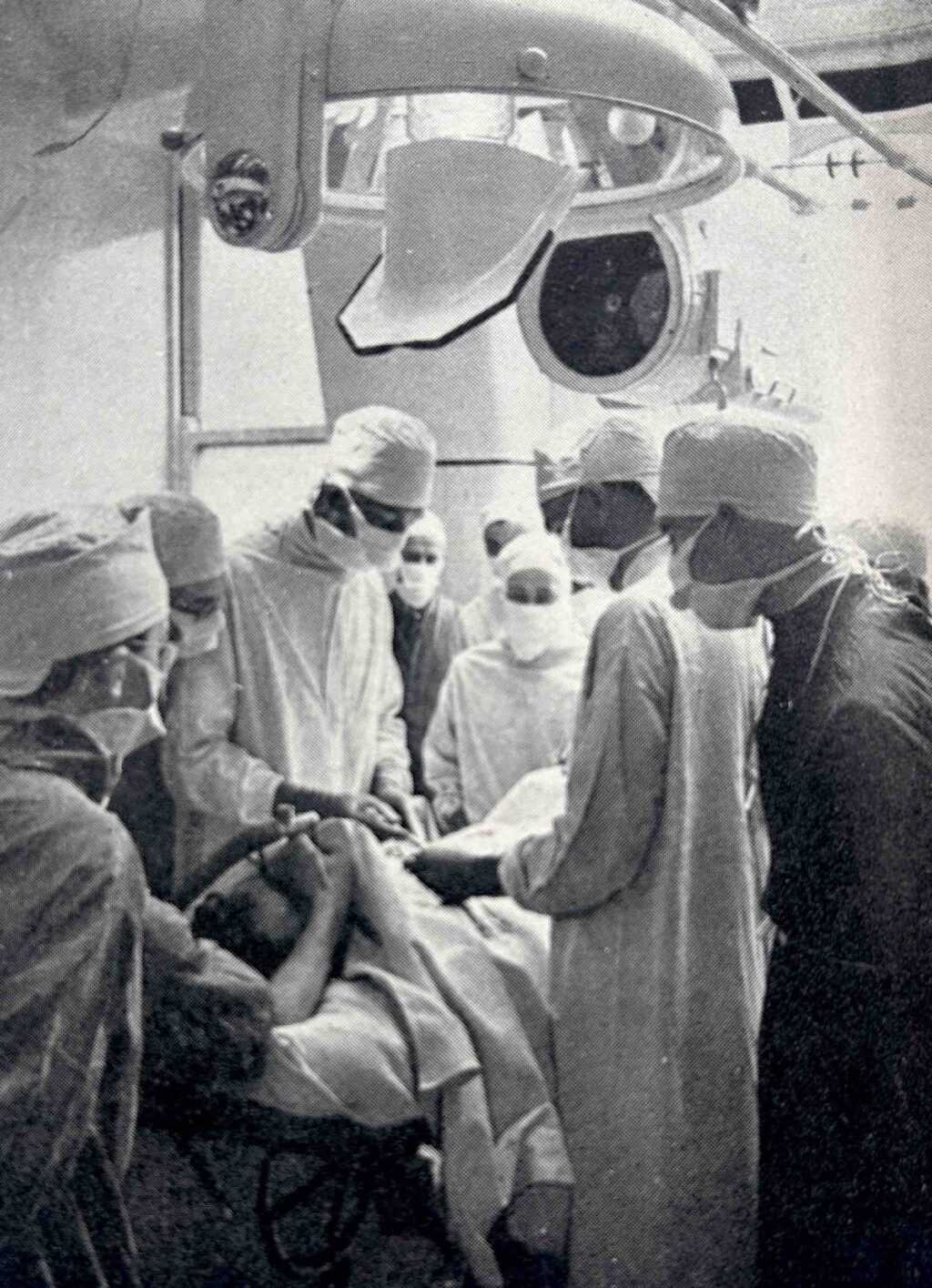

In May 1949 Guy’s Hospital, London, installed the first permanent equipment for televising operations. The television unit was specially designed for this purpose by EMI, and consists of an overhead lighting unit, microphone, and camera, with remote control of movement, focusing, and lens selection (one lens giving a magnified close-up).

The circuits are designed to exclude diathermy interference from neighbouring hospital apparatus. The camera uses the CPS-Emitron tube and is specially sensitive to colour variations at the red end of the spectrum. Definition in this unit is on the BBC standard of 405 lines, but it is proposed to use 605 lines later.

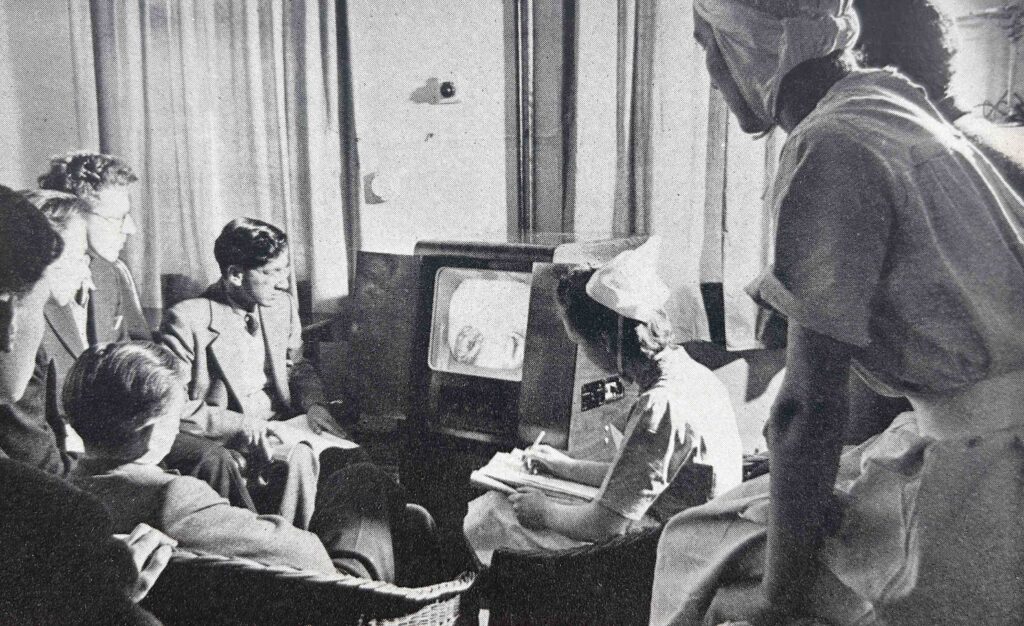

In his 1950 book Adventure in Vision, John Swift notes that this initiative followed one in 1947 by RCA Victor in a New York hospital, with operations seen by members of the American College of Surgeons at the Waldorf-Astoria. As well as including the photograph above of the Guy’s set-up, Swift adds, in a caption:

The camera is on an overhead ‘railway’ and the part of the body being operated on is reflected into the lens by the mirror inclined at 45 degrees. The surgeons comments are picked up by microphone.

The header image is also from Swift, with this caption:

An unretouched photograph taken during an operation at Guy’s. Students have a perfect view of the surgeon’s hands at work.

Remarkably, BBC Newsreel made a detailed two-minute film item about this work, which can be viewed here as part of the BBC Archive strand on Facebook (although frustratingly I don’t think it has been added to their Youtube collection, and so I can’t embed it.)

In Adventure in Vision, Swift also includes intriguing details of a further system:

Soon after the equipment at Guy’s was brought into use an operation was seen on marconi equipment at St Thomas’s Hospital. It was a delicate eye operation, including the application of diathermy for a detachment of the retina.

In the operating theatre the surgeon was looking at and operating upon an eye measuring approximately one and a half inches across. On the television screen students saw an eye nine inches across.

My next step is to dig into contemporary newspapers and also medical journals to see if I can uncover more about these pioneering applications.

Brilliant John – if I could, I’d pre-order this now!