An introduction to Osborne

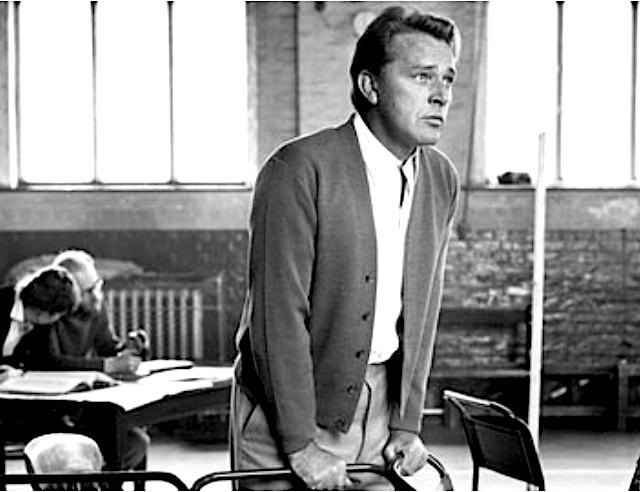

John Wyver writes: Yesterday, as part of the Richard Burton: Muse of Fire season at BFI Southbank I gave an ‘extended’ introduction (that was the request) to a rare screening of the BFI National Archive’s 35mm print of John Osborne’s 1960 television play A Subject of Scandal and Concern. Above is a rather fine BBC image from rehearsals.

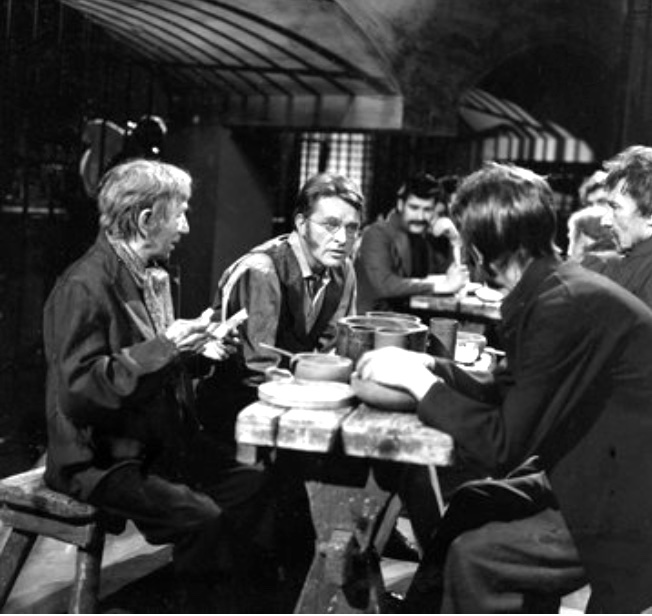

The print looked really good and a decent crowd seemed to appreciate the Tony Richardson-produced drama, which stars Burton as the Victorian secularist George Holyoake. What follows is a lightly edited version of my notes – and if you missed the occasion, although I cannot condone this, you may be able to seek out the low-res version of the play that has been on a well-known streaming site for the past year.

Let me start by taking you back sixty-five years to 1960, and to the early evening of Thursday 21 April. Ten days into rehearsals for the play you are about to see, A Subject of Scandal and Concern, and just four days before it is to be recorded in Riverside Studio 1, BBC Television flack Nest Bradney has organised a meet-and-greet with star, writer and director.

Among Fleet Street’s finest attracted by a courtesy cocktail is Kenneth Passingham, show business correspondent for the Sunday Dispatch. For his weekend column, he files a note about the occasion that reproduces – without comment, as he says – views expressed by the team.

Richard Burton: ‘I don’t think this play will be very successful on TV. The language is elaborate. I suspect it will be too much for the audience.’

John Osborne: ‘If I thought the play was bad, I would never have submitted it. But it is not a great play. It is interesting. A bon bon compared with the big screen.’

Tony Richardson: ‘Television is as good as the people who do it. It is ideal for news, interviews, and sport. No one is going to do major work for it. For that we go to the films or theatre.’

I somehow doubt that Nest went home especially happy that evening. Nonetheless, before you ask for your money back, let me assure that A Subject of Scandal and Concern is a lot more interesting than these dour comments might suggest. My task over the next 15 minutes or so is to suggest why that may be the case.

The writer

Let’s start with the script, which was commissioned as an original television play by Granada and submitted by writer John Osborne at the end of 1959. With what Osborne called ‘peremptory haste’, it was turned down. But then – and it’s remarkable to me that these deals were reported blow-by-blow in the newspapers – it was sold almost immediately to Associated-Rediffusion. A-R however decided not to take it into production, and almost immediately the BBC picked it up.

Before a contract was issued, Controller of Programmes, Television, Kenneth Adam had his doubts about the script: ‘I would not have thought it likely to be successful,’ he wrote in an internal memo.

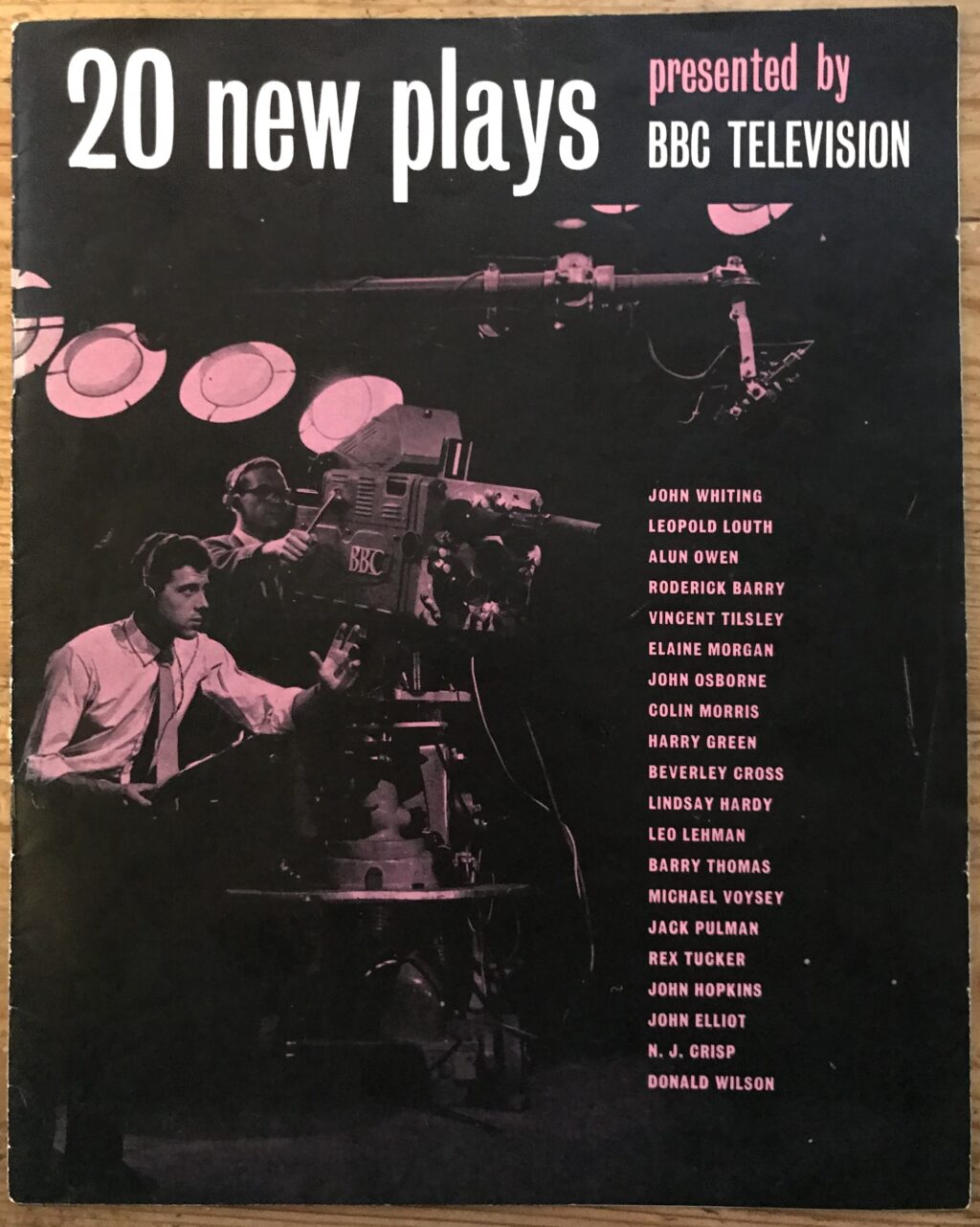

But Burton and Richardson were attached, and Head of Drama Michael Barry was keen, not least because he was pulling together for that autumn an ambitious series of original television dramas by some of the most prominent and promising writers of the day, including John Whiting, Alun Owen and Elaine Morgan.

20 New Plays was Barry’s response to the attention, and often substantial audiences, that ABC’s Sunday evening strand of written-for-television plays, Armchair Theatre, was attracting under Sydney Newman, ABC’s Head of Drama from April 1958.

Responding to gritty social realism loosely characterised as ‘kitchen sink’ plays emerging from Royal Court and elsewhere, Newman had focussed Armchair Theatre on urgent contemporary stories by emerging writers including Owen, Clive Exton and Harold Pinter.

For Barry, a play by John Osborne, the writer who at the Royal Court had given birth to this new drama with his 1956 Look Back in Anger, recently released as a feature film, had the potential to significantly enhance 20 New Plays, especially with the film’s star and director on board.

Typically, Osborne later wrote that ‘most of the people on the executive level [of television] are dim, untalented, little bigots.’

By 1960 the thirty year old playwright had followed up the immense success of Look Back in Anger with The Entertainer, which opened at the Royal Court with Laurence Olivier in the lead role in April 1957. Then at London’s Palace Theatre in May 1959, Osborne opened the satirical musical – and critical disaster – The World of Paul Slickey. A Subject of Scandal and Concern was the writer’s next script to be produced.

Osborne by this time was the focus of intense tabloid interest, for his marriage to Mary Ure which was falling apart, and for his flight to Europe with the costume designer Jocelyn Rickards. The press is one of the consistent targets of his plays at this time, with bitter criticism directed at hacks in both Paul Slickey and A Subject of Scandal and Concern.

In contrast to the reception given to Slickey, critics were broadly positive about the film of Look Back in Anger, which was released in September 1959, and in which Richard Burton took over the role of Jimmy Porter, created on stage by Kenneth Haigh.

The director

Director Tony Richardson, who had staged both Anger and The Entertainer before turning down Paul Slickey. In 1959 he formed Woodfall Film Productions with Osborne and producer Harry Saltzman, and had directed the films of Anger and, shooting in November 1959 as Osborne was completing the script of A Subject of Scandal and Concern, The Entertainer, which was to be released in July 1960.

In the second half of the 1950s, Richardson had juggled his theatre work with involvement in the Free Cinema movement, co-directing Momma Don’t Allow with Karel Reisz in 1955, and a far from happy apprenticeship as a studio director for BBC Television.

In his enjoyable memoir Long Distance Runner, Richardson paints a vivid picture of the BBC Drama Department in the late 1950s:

Attending the meetings.. was to me totally disillusioning – none of the directors ever saw a movie or a play, but they talked about their own middlebrow productions as if they were discussing the Festival of Ephesus… I knew straight away that the BBC wasn’t for me. So did the BBC.

Nonetheless, Richardson achieved a number of distinctive productions, including an Othello in 1955 with the Black actor Gordon Heath, and Box for One, a one-man drama set in a telephone booth penned by Peter Brook.

Then for a television adaptation of a Chekhov’s short story Richardson cast George Devine in the central role, and it was Devine who with Oscar Lewenstein, Ronald Duncan and Greville Poke in 1954 founded the English Stage Company and purchased the Royal Court Theatre. Which led to Richardson staging the company’s third production, Look Back in Anger.

Devine has a further walk-on part in this story, playing Mr Justice Erskine in Scandal and Concern, as does another actor closely associated with British new wave cinema, Rachel Roberts, who takes the somewhat thankless role of the central character’s wife.

The star

As the current season illustrates, by the time he took the film part of Jimmy Porter, Richard Burton had been acting in films for a decade, and on stage for rather longer, including in Shakespeare’s Henriad at Stratford-upon-Avon. His first Hollywood role was in 1952 in My Cousin Rachel, and this was followed by more Shakespeare and a number of largely forgettable films

The film of Look Back in Anger was shot in the autumn of 1958, and two more of those forgettable films followed in 1959, The Bramble Bush and Ice Palace, neither of which feature in this season and the second of which Burton called, if you’ll excuse my language, ‘a piece of shit’. His Warner Bros. fee for both movies was $125,000 but his dissatisfaction with them was presumably a factor in his decision to sign on for Scandal and Concern for just £1,000.

I say ‘just’ but this was noted in the press as the highest fee that British television had paid to an actor to date, and was a significant proportion of the cash budget (that is, costs excluding facilities and production staff) of 4,725 pounds and 2 shillings. In comparison to Burton’s grand, George Devine took home 262 pounds 10 shillings, Rachel Roberts 133 pounds and 7 shillings, and John Freeman, a relatively modest 63 pounds.

The production

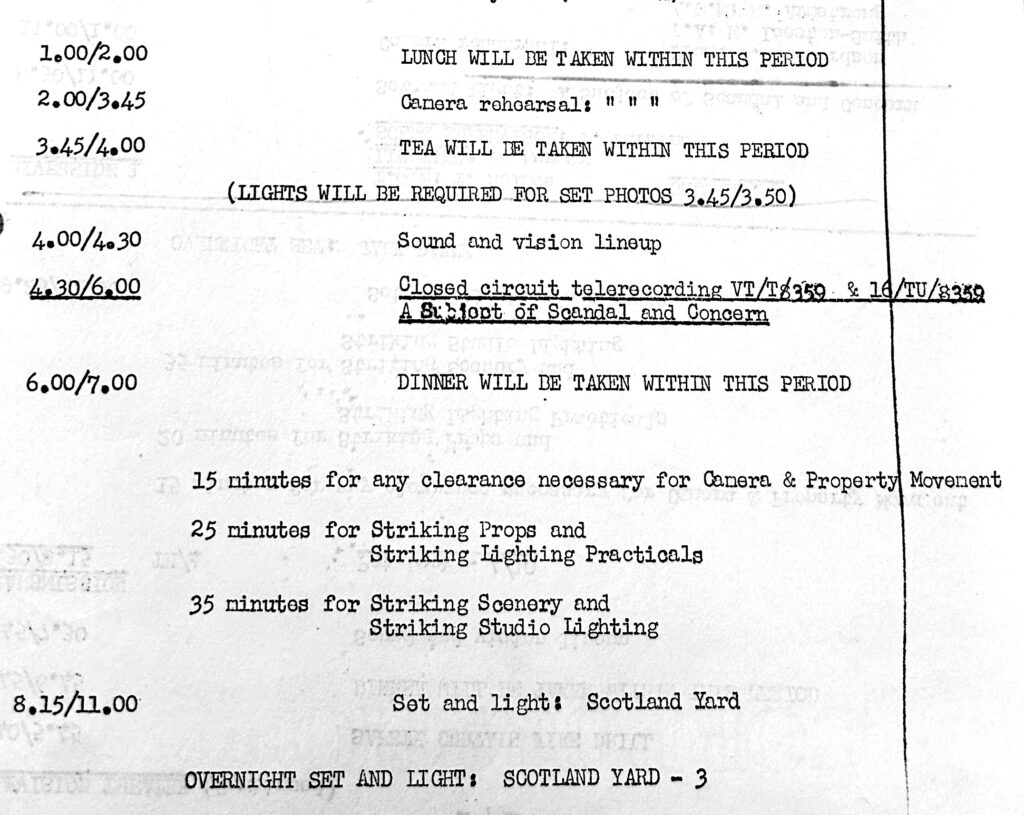

Once Michael Barry had committed to the script, everything came together very quickly, with rehearsals from the 11 to 22 April at St Gabriel’s Hall, SW1, then two days of camera rehearsals at Riverside Studios on 23 and 24, with recording, after a further session of camera rehearsals, between 4.30 and 6pm on Monday 25.

The running order indicates 190 shots in a succession of 14 settings, for a running time of 61 minutes, which gives you a sense of how pressured as-live production was in those days, not only for the cast but also for the incredibly skilled studio crews. After the allocated 90 minutes, Studio 1 needed to be re-set for an episode of Scotland Yard.

Again, in Long Distance Runner, Richardson recounts an engaging story about the recording.

In the primitive days of TV tape recording when it wasn’t possible to cut or edit tape, you could only record as if it was a live performance. The foreman of the jury, a bit-role actor, had only one line, ‘Guilty, my lord’, but during the shoot he was so carried away by the magnificence of Richard’s performance, that he shouted ‘Not guilty’. And we had to reshoot the whole play.

Like many good stories, this is a touch economical with the actualité, for the production paperwork preserved at the BBC Written Archives Centre, has no indication of this, apart from a note that two retakes towards the end were necessary, totalling just under 12 minutes.

The production was recorded to both 2-inch Ampex videotape, a relatively recently introduced technology, and also as a tele-recording (that is, filming from a screen) to 16mm film, for possible distribution. This seems to have been fairly standard at the time, certainly for prestige productions, with the videotape later wiped after transmission.

We’re showing a fine 35mm print today from the BFI National Archive, and the provenance of this is a bit of a mystery, but it may well be that in the early days of the Archive taking in television programmes, requesting a preservation copy on 35mm was standard. In any case, I want to do a little more research about that.

The play

A Subject of Scandal and Concern features scenes from the private and public life of the English teacher, secularist and social missionary George Holyoake, 1817-1906, and focuses especially on events in 1842 when Holyoake, at the age of 25, became one of the last persons in England to be convicted of and imprisoned for blasphemy. (The image below is of Holyoake’s grave in Highgate Cemetery).

Critics and commentators have, it is fair to say, been puzzled by the play, by its low-key drama documentary tone, and by its apparent lack of a dominant argument. Clearly it is in part a passionate Osborne-ian defence of freedom of conscience, and it is also about what one writer has called ‘the birthing of a voice’, rather literally so in that Holyoake has to overcome a stutter to defend himself in court.

As Luc Gilleman notes in his study of Osborne, ‘Richard Burton portrays the character most effectively, as a man uneasy in body and speech, a man seen frequently looking down, as if to gather thoughts that have tumbled to his feet…at once humble and stubborn.’

But Osborne complicates all this by introducing, in an echo of certain of the Brechtian techniques of The Entertainer, a frame around the historical scenes with a present-day narrator, who speaks directly to the viewer.

In the script the character is a lawyer, but in the broadcast he is played, effectively as himself, by John Freeman, the former Labour MP turned journalist (he was soon to assume the editorship of the New Statesman) and formidable television interviewer, well-known at this point for his Face to Face series.

The production paperwork reveals that Richardson wanted American newsman Ed Murrow for the role, and for the narrator’s sequences to be filmed in New York, but Murrow was unavailable in Japan.

The narrator’s final speech is an arrogantly dismissive message to the audience:

If it is meaning you are looking for, then you must start collecting for yourself. And what would you say is the moral then?

Then in a line that seems to have been left over from the script’s time with the ITV companies, he says,

If you are waiting for the commercial, it is probably this: you cannot live by bread alone. You must have jam-even if it is mixed with another man’s blood.’

And he concludes, at least in the published script,

That’s all. You may retire now. And if a mini-car is your particular mini-dream, then dream it. When your turn comes you will be called. Good night.

Except that for the broadcast version, the BBC clipped out, ‘And if a mini-car is your particular mini-dream, then dream it.’

The broadcast

Transmission came round a little over six months after the taping, with the play scheduled by Kenneth Adam on Sunday 6 November at 10.10pm, significantly later than the traditional 8 or 8.30 start of the Sunday evening play. It also carried a warning that the subject matter ‘was not suitable for children’, which seemed absurd to the press and many viewers .

In fact, this wasn’t – or so he claimed – Adam’s intention, and he had prepared a somewhat convoluted press statement to the effect that there were rare occasions when he needed to

rebuild the evening so as to ensure that every single person who wants to, can watch… The nature of [the play’s] theme is such that it will gain rather than lose by being placed late in the evening.’

One might suspect, however, that his earlier concerns about the script remained, and in fact it was seen by just 9% of the potential viewing audience.

The response

Press reaction was mixed, with the anti-s outnumbering the pros. Maurice Wiggin in the Sunday Times was typical with a complaint that the drama was simply boring:

I was not surprised to find arrogance and contempt in John Osborne’s first play for television, but the last thing I looked to find was dullness.

On the other hand, Maurice Richardson, writing for the Observer praised

an exceptionally good play… one of the most genuinely high-minded pieces of uplift to be shown on television for a long time. … The remarkable thing was the way Osborne managed to project himself on to this character and give so strong an illusion of reviving the ambiance of the 1840s, while preserving Holyoake’s obsessional cussedness. This was a display of dramatic talent of a high order.

The Times praised Burton’s ‘intelligent’ portrayal, and Anthony Cookman in The Listener wrote that that the actor

gave a gentle and persuasive performance which at least allowed him to work up a degree of much-needed indignation in the trial when he pleaded for toleration and freedom of opinion.

According to the audience research report, the audience reaction index came in at 62, slightly below average for plays of this kind, but there were some damning comments from viewers. ‘Cannot the BBC tear itself away from the dreary, boring round of plays which are being inflicted on the public Sunday after Sunday,’ asked an indignant works foreman. And a schoolmaster described the play as ‘a boring, pointless piece of propaganda.’

Nonetheless more than half the sample that made up the audience research panel

appear to have found this a gripping, powerful and thought-provoking drama on a theme of deep concern to everyone.

Moreover, most viewers agreed about the high quality of the acting:

Superb, brilliant, masterly, were among the epithets scattered profusely among the comments on a performance in which [Richard Burton] had apparently surpassed himself in a very difficult role.’

Critics of the production, however, further complained of ‘slow movement, drab settings, dim lighting and jerky cutting here and there’, but – and this is how viewers were identified in these reports — a serviceman’s wife ‘found the whole production admirable.’

In retrospect, A Subject of Scandal and Concern can be seen as a kind of trial run for Osborne’s far more successful and substantial play Luther, which opened in June 1961 in Richardson’s production, with Albert Finney, and which was produced as the first BBC Television Play of the Month in October 1965, with Alec McCowen.

Like Scandal, Luther has a lightly played Brechtian framework and draws contemporary relevance from the lives of historical characters. Both Holyoake and Luther are men out-of-step with society, and each is utterly incapable of compromise.

Let me end with two final comments. In his fine 1988 biography Rich, Melvyn Bragg has this to say about Burton’s performance, which I feel we can agree upon:

Burton here was directed to play a character role and responded so well that you could imagine he had been doing it all his life. Once again, given the words and the director, he seized the chances.

And in his Diaries, writing a decade after the production in September 1971, Burton himself recalls not only his pleasure at staying at the Savoy during rehearsals for the show, but also – in his mind at least – its reception:

The whole thing was a huge success and I must try to get a copy for the boat.

I have failed to discover whether he did in fact acquire a print for his nautical screening room, but perhaps you might like now to imagine that you are bobbing gently up and down with Richard watching alongside you. In any case, I hope you find this rare showing an interesting and enjoyable experience.

With thanks to Ian Greaves, James Jordan, Louise North, Billy Smart and John Williams for their assistance with the research for this presentation.

Leave a Reply