Let us now praise Pallant House

John Wyver writes: To Chichester by train last Saturday for a visit to Pallant House Gallery, both to see the current William Nicholson exhibition (on until 10 May) and to have lunch at Pallant Café, which for me is the country’s best restaurant run by a cultural institution. May I especially recommend the Welsh rarebit?

Pallant House, with its exceptional permanent collection of modern British art and its intelligent programme of temporary exhibitions is without question our best gallery, excepting only Tate, for looking at 20th and 21st century art. Combining a visit with the rarebit and then a matinee at Chichester Festival Theatre, as well as the town’s very fine Lakeland, is close to a perfect day out, although at this time of the year the stage offerings are limited.

The gallery is a combination of an exceptionally fine Queen Anne townhouse and a modern extension designed by Colin St John Wilson with Long & Kentish, which opened in 2006. Together they offer a near-perfect combination of human-scale spaces, both for the display of an exceptional permanent collection and for mounting mid-level exhibitions in a suite of six or seven rooms.

The permanent collection is built on a remarkable group of works left to the city of Chichester in 1977 by the Church of England priest Walter Hussey. Throughout his career, including as Dean of Chichester, Hussey commissioned a wonderful range of visual artists, including Henry Moore, Graham Sutherland, John Piper and Marc Chagall, and composers, among whom were Benjamin Britten, William Walton and Leonard Bernstein.

Hussey’s collection at Pallant House has been expanded with a number of major gifts, including works given by Colin St John Wilson, and by thoughtful complementary acquisitions, many of which come from emerging artists in Britain. And alongside this display, over the past decade and more, the gallery has mounted an increasingly confident and truly wonderful series of exhibitions of twentieth century British art.

Shows that I have especially enjoyed include retrospectives of Ivon Hitchens (2019), which was a particular revelation, Glyn Philpot (2022), Gwen John (2023) and John Craxton (2024), as well as exceptional thematic exhibitions devoted to British art responding to the Spanish Civil War, Conscience and Conflict (2015), The Mythic Method; Classicism in British Art 1920-1950 (2016), and The Shape of Things: Still Life in Britain (2024).

The still life show, co-curated by Dr. Melanie Vandenbrouck, the gallery’s Chief Curator, and Miriam O’Connor Perks, the Assistant Curator, is an especially good example of a perfect Pallant House project that was, once it was conceived, so obviously a great idea, but which no other gallery had attempted in recent years. Many of the other shows were curated by the gallery’s Director Simon Martin, often working partnerships with other curators and art historians:

Coming up next is British Landscapes: A Sense of Place (30 May – 1 November), followed by Barbara Hepworth and Greece, together with an Alfred Wallis show (both 21 November – 11 April 2027). And on the walls now, along with Mothering, a presentation of paintings by Caroline Walker which I was a touch underwhelmed by, is the exceptional William Nicholson exhibition.

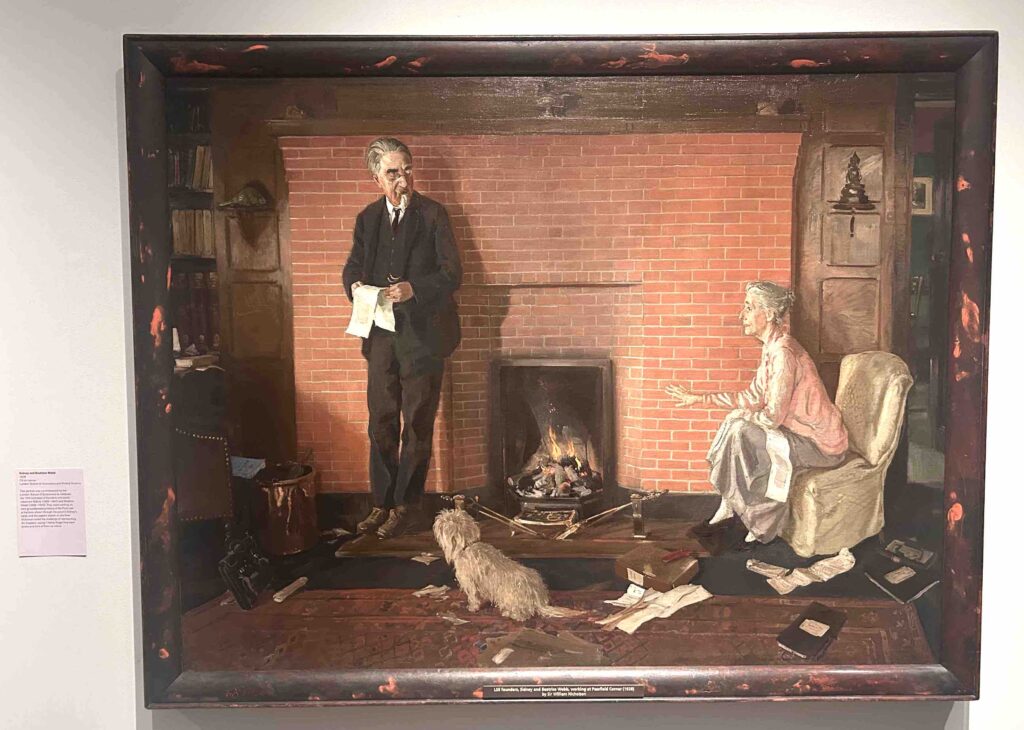

Nicholson, amongst much else the father of the more celebrated Ben, was a painter and print-maker who career spanned the final years of the Victorian age through the immediate aftermath of the Second World War. A fashionable portraitist, he captured numerous significant figures of especially the Edwardian era, as well as Sidney and Beatrice Webb, in the large, late-ish (1928) double figure canvas commissioned by the LSE (reproduced as the header image).

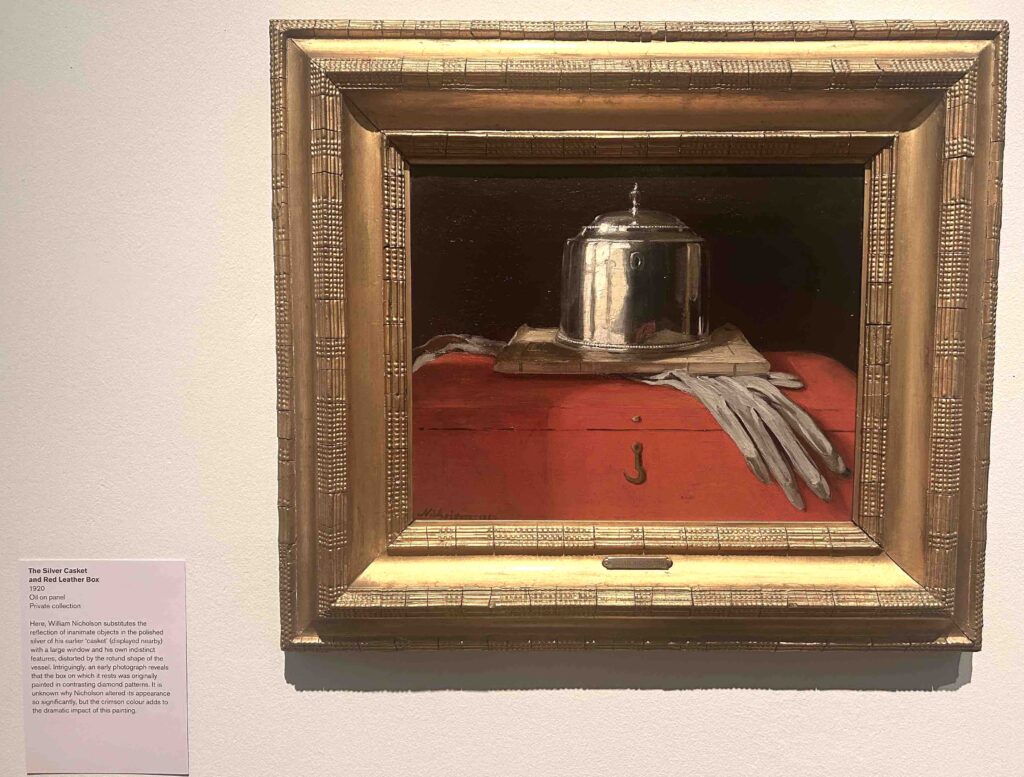

Perhaps most celebrated today for his exquisite and immensely popular still lifes, Nicholson achieved an extraordinary facility for surfaces and light, as in The Silver Casket and Red Leather Box, 1920 (below).

But the exhibition also features a range of the landscapes that he painted throughout his life, some of which like Mending the Nets, Rottingdean, 1909 (above), are astonishing in the effects they can conjure up with the just a very few, spare brushstrokes. There are surprises too, like Armistice Night, 1918 (below), which is a small-scale cityscape and history painting.

I found the show completely fascinating. As for the views of others, see the reviews by Laura Cumming for The Observer, which is a typically brilliant, thoughtfully ambivalent response, and, with full-on enthusiasm, David Trigg for Studio International.

I love Pallant House, its collection and its great special shows. The only problem – and mystery – is their total resistance to film as a medium alongside the others they champion. There have been many opportunities for collaboration with the local arthouse and festival, but I gather all have been rebuffed. Odd, considering the importance of film in Neo-Romanticism, one of their major interests. But this hostility clearly comes from the leadership – not unusual in my experience of other major English galleries. (the Hayward has carefully edited out a number of film-related exhibitions from its history – inc ones i’ve curated!).