Magic Rays of Light at BFI Southbank 2.

John Wyver writes: The BFI Southbank season continues tomorrow, Thursday 15 January, with an early evening screening in NFT2 of two remarkable programmes. First is a 1970 edition of the BBC2 arts magazine series Review which features a recreation of the 30-line broadcast from 1930 of The Man with the Flower in his Mouth. The original production team are reunited forty years after the original transmission to give a unique insight into the making of early television.

Following this is Jack Rosenthal’s 1986 drama The Fools on the Hill, a loving, comic (and highly inaccurate) imagining of events at Alexandra Palace leading up to the first night of the BBC’s high definition service on 2 November 1936.

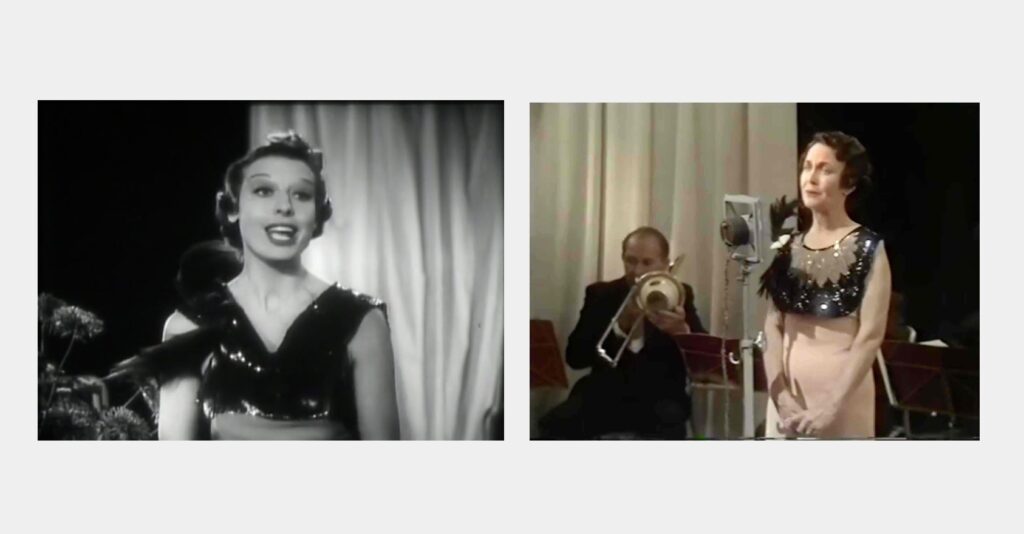

I’ll be providing an introduction and tickets are still available. Meanwhile, following is the text of the programme note that I have written for the evening. And the image above pairs Pat Whitmore as Adele Dixon from The Fools on the Hill with the real deal in Television Comes to London.

The Man with the Flower in his Mouth

‘It was I,’ claimed Sydney Moseley, business partner and relentless booster of John Logie Baird, ‘who suggested the production of the first television play.’In fact the specific idea came from BBC executive Val Gielgud. A note dated 3 April 1930 proposed the play by Luigi Pirandello as a way ‘to watch the various developments [in the Baird operation] from our own point of view’.T

his was all of a piece with the growing awareness that the BBC should go beyond simply providing technical assistance to the Baird company and become more involved with output.

Sibling of the celebrated actor John, thirty-year-old Val Gielgud had been the BBC’s director of productions, with responsibility for all drama and variety, for just over a year.‘With unfailing judgement for the requirements of a new medium,’ producer Lance Sieveking recalled, ‘Val chose Pirandello’s The Man with the Flower in his Mouth. It had only three characters and was very static.’

The play is dark, at times defiantly opaque, misogynistic, and yet with an exhortation of carpe diem at its heart. Even recognising the pragmatic necessity for a play of modest scale, it was a strikingly eccentric selection.

Sieveking spent some days adapting the play ‘so as to get as much movement as possible in the few inches available on the tiny screen, which was little bigger than a postcard.’He also commissioned four panels of boldly sketched ‘scenery’ from the modernist painter C.R.W. Nevinson.

Working mostly with vertical lines, which the Baird transmitter responded to better than horizontal ones, Nevinson painted a scene-setting image of a pathway, trees and the moon together with three designs suggestive of point-of-view shots of café tables.

Clearly briefed by Sieveking, one previewer of the broadcast wrote that ’the spectator will follow the thoughts and words which an actor is expressing. The conversation will continue, but the eye will be led on to watch the motion of hands and other objects about which the voice is talking.’

There was even a tentative approximation of a cinematic over-the-shoulder shot, as Sieveking reported after his second rehearsal: ‘a very satisfying effect is obtained in which the back of the nearest speaker’s head is seen, while beyond it, smaller, the face of hisvis-a-vis’.

After the rehearsals with Earle Grey, who played the Man, Lionel Millard, who was the Customer, and Gladys Young, Sieveking wrote: ‘The cast seemed to enjoy every minute…, getting a lot of amusement from the fact that in order to show them sitting one on each side of the table their heads had to be actually touching, and even then only half of each head was visible.’

The producer believed that he was working through fundamental issues about how television might develop. ‘I have devised a production method and a television dramatic script,’ Sieveking noted just before the transmission, ‘which I hope may be the foundation of the future technique.’

Not that everyone on the BBC side was enthusiastic, as Asa Briggs recorded: ‘Only one figure could be projected at a time and that figure could scarcely move. The focus was still uncertain and variable. George Inns, a 16-year-old trainee who arranged the effects, felt that it was all very primitive and that television had no future.’

A reconstruction of the 1930 broadcast was mounted in 1970 for a studio edition of the BBC2 arts programme Review. Editor and presenter James Mossman gathered together the original cast and Sieveking, engineers Tony Bridgewater and D.R. Campbell, effects men George Inns and Brian Michie, and stage manager Mary Eversley, and after reminiscencing they re-made a few minutes of the transmission.

Although the aspect ratio is wrong and the lighting poor, the team did attempt to wrench the red-toned, rapidly flickering image into the two-shot that Lance Sieveking had sought so avidly, At the close Mossman spoke again with Bridgewater, who in later years proved to be the most acute and clear-eyed of the pioneers.

Was there a chance, Mossman asked, that Baird’s mechanical system used for The Man with the Flower in his Mouth could have caught on, rather than being swept aside by Marconi-EMI’s electronics. ‘Sadly, I don’t think so’, Bridgewater replied. ‘Mechanical television was cumbersome, inefficient, and it really never had a chance of competing in the long run with the electronic methods.’

Was Baird then, Mossman probed, a failure? Bridgewater demurred, scrupulously fair-minded: ‘He was the first man in the world, wasn’t he, to demonstrate true television. And I think he made everyone aware of the potential of television.’

Excerpted from Magic Rays of Light: The Early Years of Television in Britain by John Wyver

The Fools on the Hill

Fifty years ago next Sunday, the question must have been whether BBC television would survive the week. In Jack Rosenthal’s hilarious account of that dies tremendus, The Fools on the Hill (BBC 2), the world’s first television service was flying by the seat of its pants.

With inadequate staff, ludicrous funding, almost total lack of experience, and two incompatible technical systems wished on it, the start of television was in the finest British tradition of muddling through.

What really threw the Ally Pally pioneers-“Fools on the Hill,” as the rest of the BBC christened them-was the news that they had nine days to prepare for a live demonstration at RadiOlympia, instead of three months to go on air.

Starting from roughly the same position as Columbus, they worked round the clock to build programme schedules, rehearse the performers, and try to get the machinery right. “What happens if I forget my words?” asked a petrified presenter. “They’ll just think we have lost· the sound,” Cecil Madden reassured her.

Whether this was a real exchange, or one of Mr Rosenthal’s inspired inventions, hardly matters. This was a piece of theatre, about a real situation; Rosenthal had done his research in the Written Archives (a kind of broadcasting Domesday Book), and woven his fictional bits around them.

For the purposes of conveying the wonder of the occasion he invented a junior technician, David (Nicholas Farrell), totally obsessed with his walk-on part in making history, and oblivious to the advances of Florence (nice girl in canteen) and Wendy (cut-glass secretary from Broadcasting House). I confess I found the triple affair a touch cloying.

But the rest was pure gold; if it went very slightly over the top, well, all the documentary accounts suggest it wasn’t very far over. The Baird system was as horrific to work as the play suggested (“I get insult upon insult,” lamented the Father of Television) and the rival Baird and EMI geniuses did toss to decide which system went first.

Purest gold of all came from Shaughan Seymour’s faultless wing-and-prayer performance as Madden, the imperturbable first Programme Organiser, urbanely dispensing the oil of one-liners on every looming disaster.

Richard Last, Daily Telegraph, 28 October 1986

Leave a Reply