OTD in early British television: 22 August 1932

John Wyver writes: At just after 11pm on Monday 22 August 1932, the BBC began a television service using Baird company 30-line technology. Baird Television Ltd had been broadcasting since November 1929, at times with limited BBC support, but now responsibility for transmissions lay fully with the BBC. Looking back, John Logie Baird believed that handing control of the 30-line service to the BBC was a mistake:

We had in Long Acre [where his company was based], in effect, a rival broadcasting system to the BBC, with our own independent production being received by the public. This came to an end when the BBC took us over and I often regretted this and thought that we would have been better to have continued operating independently.

The decision was taken before Gaumont-British’s purchase of the majority stake in the Baird company, but since the new owners were interested in selling receivers, not in subsidising a programme service, the conglomerate approved. By the spring of 1932 it was agreed that initially there would be four half-hour broadcasts each week, and that although the BBC could change the number of transmissions the service would continue until at least 31 March 1934.

The inventor’s reservations aside, ‘to us in the rank and file of the Baird Company,’ engineer Tony Bridgewater recalled, ‘the attainment of this long-sought milestone in the advancement of television was a welcome relief and satisfaction. We felt that our activities had suddenly become respectable.’

A BBC policy announcement in June envisaged a service as an extension of radio, with little sense of a separate television identity. ‘There would not be the automatic televising of every broadcast programme;’ the statement noted, ‘even if the scarcity of wavelengths did not preclude this, it would not be appropriate, for the reason that only some programmes lend themselves to vision as well as sound.’

The idea of television as an extension of the radio service underpinned the Corporation’s choice of key personnel given responsibility for the output. Overall supervision was entrusted to Val Gielgud, who since 1929 had been the BBC’s director of productions, running all radio drama and variety, and who had collaborated with Lance Sieveking on The Man with the Flower in his Mouth.

Writing in the mid-1940s, Gielgud dismissed his role in these first broadcasts, noting only that, ‘I was concerned intermittently with the earliest experimental transmissions from the basement of Broadcasting House, of which I most clearly remember the engaging antics of a performing sea-lion and his exceedingly “fish-like smell ” at close quarters.’

To produce its television broadcasts the BBC passed over the claims of pioneering producer Sieveking and brought in Eustace Robb. Between 1932 and 1935 Robb was central to the further development of the medium, and initially at least he was regarded as doing an exceptional job.

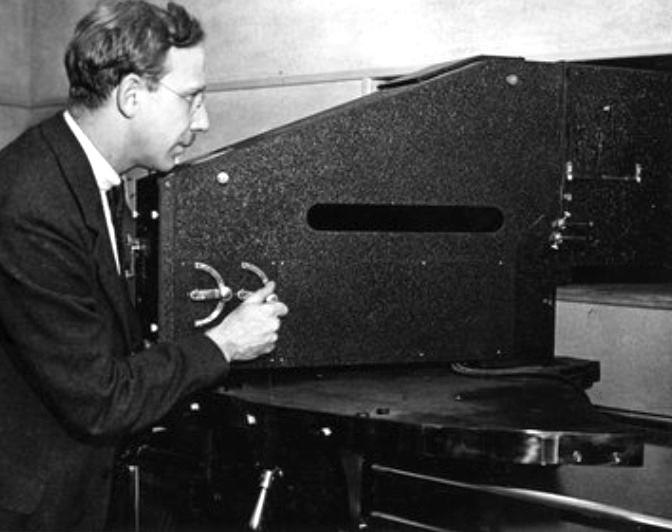

For the television broadcasts the BBC initially committed Studio BB and its adjacent control room in the deep basement of Broadcasting House. Unlike at the Baird premises in Long Acre, where there had been both a disc scanner for close-ups and a mirror-drum one for extended shots, only a single studio mirror-drum scanner was installed (pictured above). This, however, was capable of continuous focus to create a range of shot sizes, as well as being able ‘to run from side to side so as to take up different positions as rapidly as possible, and thus give greater facilities for continuity of the programme.’

The new studio was larger than that at Long Acre, being roughly 10 metres by 6 metres, but the control room was smaller. Here the BBC’s engineer Douglas Birkinshaw was joined by two key technicians from Baird’s, Desmond Campbell and Tony Bridgewater. Six test transmissions of vision preceded the first broadcast at 11.02pm on the evening of Monday 22 August.

The scene on opening night just ahead of ‘vision on’ was described by one correspondent as a kind of modernist phantasmagoria:

To the accompaniment of the piano a girl dressed in white, with white cheeks and black lips, was rehearsing an American jazz song, while the engineers were making last minute tests with the television transmitter which cast its eerie flicker across a large screen… Watched from the corner of the studio, it was all like a dream in which the actors were half human and half machine, the jazz and the flickering lights forming one of those mad backgrounds that haunt a restless sleeper.

After a few words from John Logie Baird, who clutched a sprig of white heather, there were turns from performers who mostly had experience of the Long Acre studio: Betty Bolton with French and American songs, each one set off by a different hat or scarf; Fred Douglas performing in blackface; Louie Freear, making her television debut with numbers from the musical The Chinese Honeymoon, in which she had been a sensation back in 1901; and Betty Astell with contemporary dance-band tunes.

After which, the close-up focus expanded to take in a stage that was about 3 metres square, on which Betty Bolton performed an Argentine tango as the scanner was ‘moved on its swivel base to follow her about the stage, just as a spot light is used in the theatre.’ As a kind of encore each of the four artists danced across the stage.

Reception reports indicated that the transmission was seen with varying degrees of distinctness not only across London but in Leeds and Newcastle-upon-Tyne. ‘I find that full figure transmissions are received very well,’ a viewer in the latter location reported, ‘and provide a pleasant change from the head and shoulders picture. I am therefore hoping that full figure transmissions will fill a fair share of the future programmes from Broadcasting House.’

They would have a run of more than 600 broadcasts through to 11 September 1935 to find out.

[OTD post no. 248; part of a long-running series leading up to the publication on 8 January 2026 of my book Magic Rays of Light: The Early Years of Television in Britain, which can now be pre-ordered from Bloomsbury here.]

Leave a Reply