OTD in early British television: 25 August 1937

John Wyver writes: Having noted the first activity in at Alexandra Palace in 1936 yesterday, today we make a jump on a year on to an article that marked what was claimed as television’s ‘first birthday’. Never mind that regular transmissions by the 30-line system went back to 1928, which were acknowledged briefly, this was a celebration on 25 August 1937 of what the ‘marvelling, half-incredulous crowds’ saw at Radiolympia a year before.

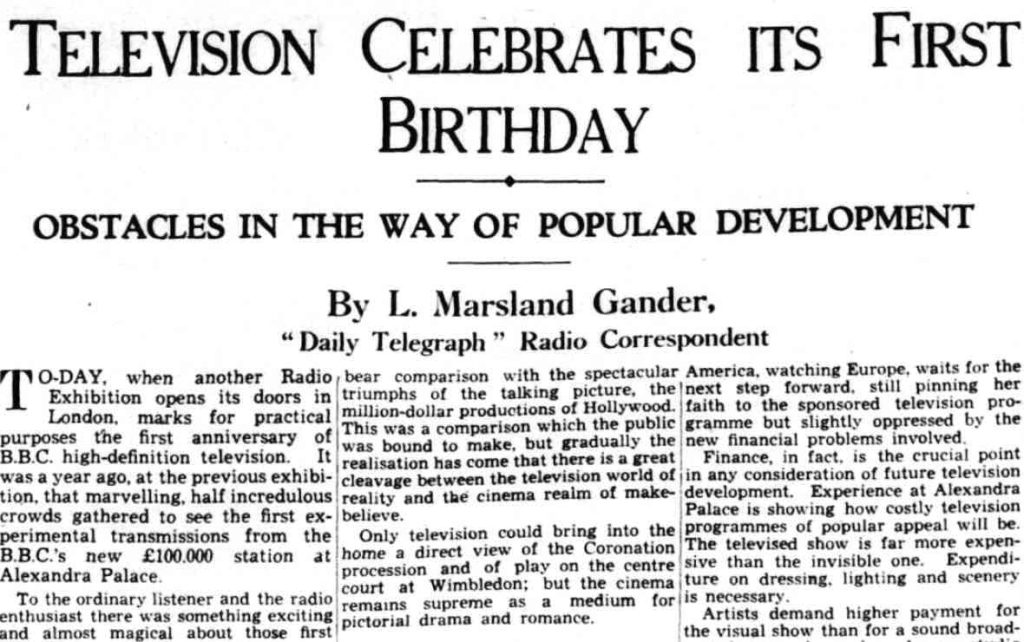

The author was the well-informed L. Marsland Gander, still by-lined as the Daily Telegraph‘s ‘Radio Correspondent’, who recalled his own first directly personal experience of the new medium:

Some days before the exhibition I had had the unforgettable experience in my own home of abstracting living pictures from the air, pictures that had been projected through space from this same station [that is, AP] nine miles away. They had been reproduced on my screen only a split second after leaving the transmitting aerial at Muswell Hill.

Twelve months on ‘the early glamour has faded and the wonder is accepted by an increasing number as a commonplace of modern life.’ Receivers were expensive, screens were small, and people were not yet buying sets in significant numbers. Moreover, many people judged the first programmes by the standards of the cinema, and consequently found them wanting. But for Gander this was the wrong way to think of television.

Only television could bring into the home a direct view of the Coronation procession and of play on the centre court at Wimbledon; but the cinema remained supreme as a medium for pictorial drama and romance.

In any case, barriers to acceptance were falling. Sets were becoming cheaper, and the reception area was growing, albeit modestly. But the key problem was finance.

Experience at Alexandra Palace is showing how costly television programmes of popular appeal will be. The televised show is far more expensive than the invisible one [that is, radio]. Expenditure on dressing, lighting and scenery is necessary.

Artists demand higher payment for the visual show than for a sound broadcast; longer rehearsals and more studio maccommodation are needed for television than for sound alone…

So the mounting tally of television cost causes the BBC to pause dismayed, while the technicians and the manufacturers push ahead.

Gander recognised that the government remained somewhat sceptical about television, and so far had resisted calls for more funding.

Meanwhile, within the limitations imposed by the means available, the television programme staff at Alexandra Palace are carrying on pioneer work which has its counterpart nowhere in the world. They have met with success and failure, but always have pushed resolutely ahead into a new country. They are building up a programme technique which is the BBC’s best investment for the future.

A separate television licence fee may be the answer, the journalist speculated, although this was only to become a reality after the coming war. Short of that,

It may be necessary, building for the future of an industry (and in the interests of national prestige), to spend more before the public will buy more.

[OTD post no. 251; part of a long-running series leading up to the publication on 8 January 2026 of my book Magic Rays of Light: The Early Years of Television in Britain, which can now be pre-ordered from Bloomsbury here.]

Leave a Reply