Performance, politics and painting

John Wyver writes: My visit to the troubled Louvre on Friday to see the glorious Jacques-Louis David exhibition, about which I posted on Saturday, prompted me to return to Leslie Megahey‘s 1986 film about the artist, The Passing Show. The first film in the trilogy Artists and Models, along with complementary films about Ingres and Géricault, this was briefly available on BBCiPlayer earlier this year, but has once again disappeared back into the inaccessible archival vaults. (You may however be able to find an illegitimate copy on a popular streaming platform.)

Unsurprisingly, given Megahey’s achievement as a filmmaker, The Passing Show is intelligent, imaginative and innovative, and streets ahead of, let’s say, the current Civilisations: Rise and Fall, or anything else recently commissioned by BBC Arts. Centred on David’s teaching studio, with James Laurenson playing the painter (below), the film eschews any detailed discussion of David’s personal life and focusses firmly on him as a political and very public artist.

There are no talking heads, and the visual elements are threefold: the paintings, filmed not in situ but via Ken Morse’s exploratory rostrum camera; reconstruction drama, presented both in colour and monochrome; and for the historical context, silent French films about the revolution. Brilliantly deployed, these film extracts are not identified, but provide epic sequences illustrating, for example, the storming of the Bastille or the executions of the Terror. In some cases, as with the coronation of Napoleon, the historical scenes are cleared based on David’s canvases.

The film studio-shot recon is exquisitely lit by DoP John Hooper, with costumes by Lisa Benjamin and art direction from Richard Morris. As in his earlier films, including Schalken the Painter (1979), and essays about Gauguin (1978) and Landseer (1981), Leslie Megahey creates precise and controlled scenes that avoid the usual clichés of such material. The core source is the memoir by painter and critic Etienne-Jean Delécluze, published in 1855, but there are quotations from others including Michelet and Charles Clement.

The only painting to be reconstructed by the film is one or other version of François Boucher‘s The Blonde Odalisque, 1751 or 1752, introduced along with the figure of Casanova in a prologue that is teasing and titillating (and all-too-typical of a predilection in both Megahey’s films and a good deal of adult television from the time).

Otherwise, the film recognises that attempts to re-stage David’s canvases for the camera would inevitably fall short and almost certainly appear ridiculous. But a recreated couch (see the header image) for the unfinished, celebrated Portrait of Madame Récamier makes a telling appearance.

The mostly unoccupied couch (another model poses there, naked, briefly) gestures towards the centrality in the film of dolls and mannequins and costuming and props and models and sets and all the paraphernalia of the theatrical. For The Passing Show (and the third word is a clue) is above all a film about performance, on stage, in courtrooms, in the streets, in revolutionary pageants and festivals, in speeches to move crowds, and ultimately in the artist’s studio.

The studio is where subjects perform to be painted, where models perform to be drawn, and where, centrally, artists perform their practice and personae. As David does, despite his speech impediment, with his crits and cracks and occasional political commentary. And as his characters perform in the canvases, which in reproduction are lingered over by the camera, looked at intensely and intently, with time (and space in the narration) to make their presences register.

There are important scenes too set on stages, with a re-enactment by sans-culottes of the oath to the Fatherland following David’s Oath of Horatii, with scenes from Voltaire’s tragedy Brutus, and a burlesque based on The Intervention of the Sabine Women. All of which echo and illuminate the theatricality of the tableaux in David’s work.

Overall, the film is very far from hagiographic, which remains comparatively rare for a major drama-documentary about an artist. David’s achievement is celebrated, but his enthusiastic embrace of Robespierre’s precepts, and those of the Committee of Public Safety, is exposed, along with the cowardly desperation to save his skin once the political tide had turned.

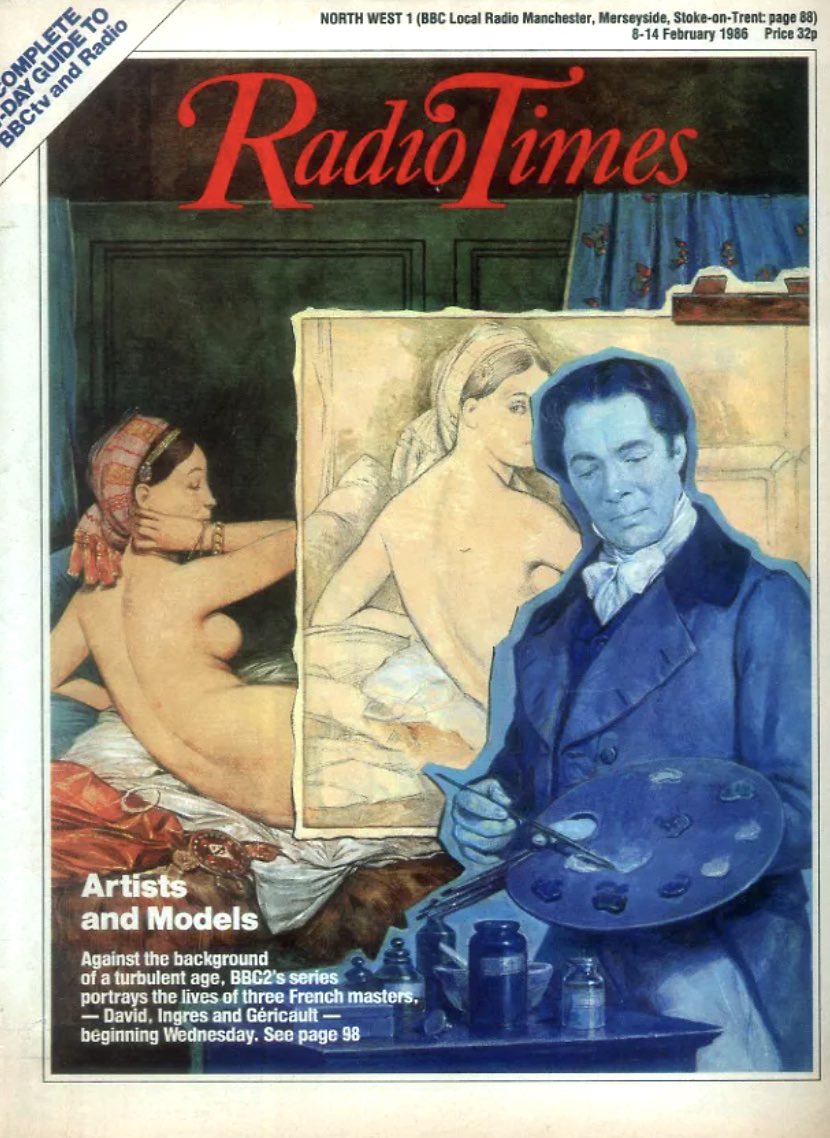

I was delighted to see how well the film stands up almost forty years on from its first BBC Two transmission in February 1986. Way back then, a preview article for which I interviewed Leslie Megahey (having written extensively about his earlier films), was the only cover feature I contributed to Radio Times, below. And since, despite the beauty of the Ingres-inspired illustration, I seem not to have kept a copy, I am naturally curious to know what I wrote.

Leave a Reply