Postcard from Paris

John Wyver writes: I have been going to Paris to see paintings for more than fifty years, and Friday was my most recent such trip. I took a break from prepping for the publication of Magic Rays of Light and the rest, and I had the pleasure and privilege of visiting Louvre’s glorious Jacques-Louis David exhibition. I also loved Minimal at the Bourse du Commerce, but I had a much harder time at the newly opened Fondation Cartier and at the Palais de Tokyo. More on all that, together with some pics, below.

I think it was the summer of 1972 when I took the overnight boat train via Folkestone and Boulogne for the first time. I had submitted an essay for the Kent College travel bursary explaining why I wanted to look at Impressionist paintings in Paris. Which is what, for more than a week, the munificent award of £30 allowed me to do.

I stayed at a student hostel near the Pantheon, and visited the Jeu de Paume, which is where the Impressionists were before the Musée d’Orsay, and Orangerie, for the cycle of Monet’s Water Lillies. I went to the Louvre and I peered down into the vast hole that five years later would become the Pompidou. And I bought my tickets at the Cinematheque in the Palais de Chaillot to see late-night screenings of Rear Window and Vertigo, the late period Hitchcocks that were then otherwise impossible to see.

As I recall, I subsisted largely on baguettes and orange juice, partly because I had so little money, but also because a painfully shy 17-year-old who lacked the confidence to order into restaurants. Apart, that is, from a self-service cafeteria on a first floor near the intersection of the Blvd St Michel and the Blvd St Germain. There you could order pasta by just pointing. Otherwise I managed from time to time to order a grand creme in a café where I would sit with a copy of Le Monde, understanding about every sixth word.

Jacques-Louis David was brimful of confidence when, after first unveiling the canvas in Rome, he took the Parisian art world by storm by showing Oath of the Horatii (above) at the 1795 Salon. And at the Louvre this is the first of a series of stone-cold masterpieces that include The Intervention of the Sabine Women, 1799 and the newly restored Portrait of Madame Récamier, 1800, both below. This glorious show, open until 26 January, marks two hundred years since the artist’s death in 1825, and as far as I can see has only been reviewed in Britain by the Financial Times and Apollo (with both reviews behind paywalls)

Blockbuster painting shows in Paris can be a particular sort of trial, with jostling queues and impossibly packed galleries, but my pre-booked experience at the Louvre was quite the opposite. The hang of the rich but not overwhelming show is immaculate in spaces that feel as if they were designed for this set of canvases, and while there were many other appreciative viewers, not for a moment did I feel crowded or uncomfortable. The whole visit was a joy, as was a sidetrip to see David’s vast The Coronation of Napoleon, 1807, which has not been moved from its usual place in room 702.

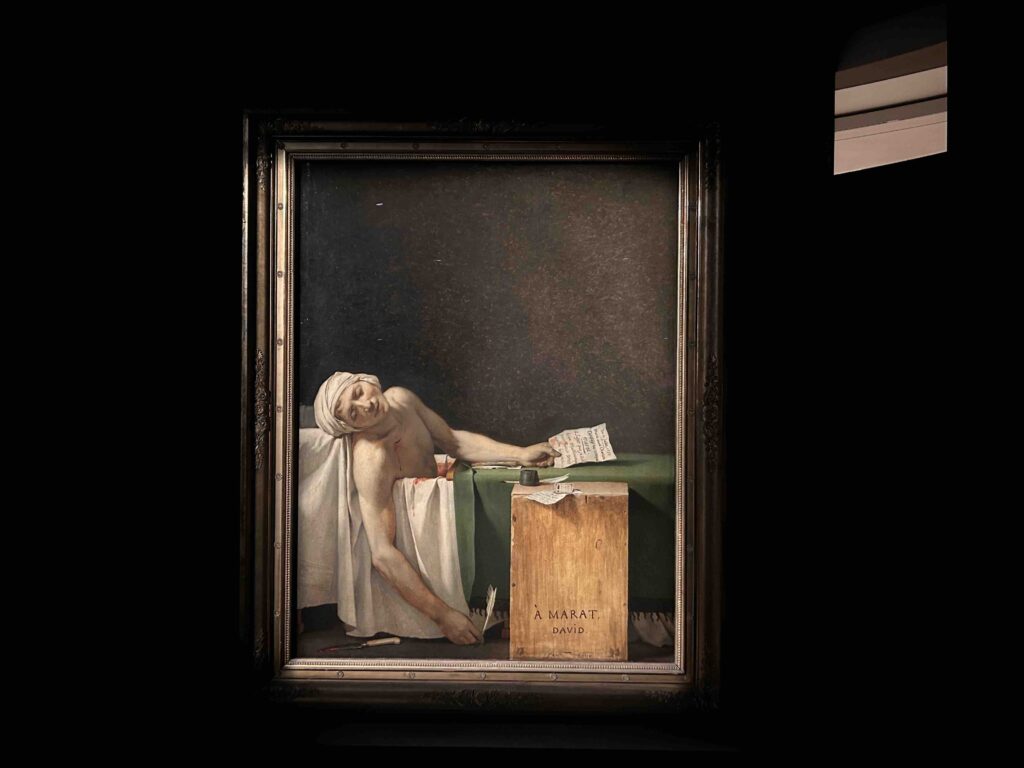

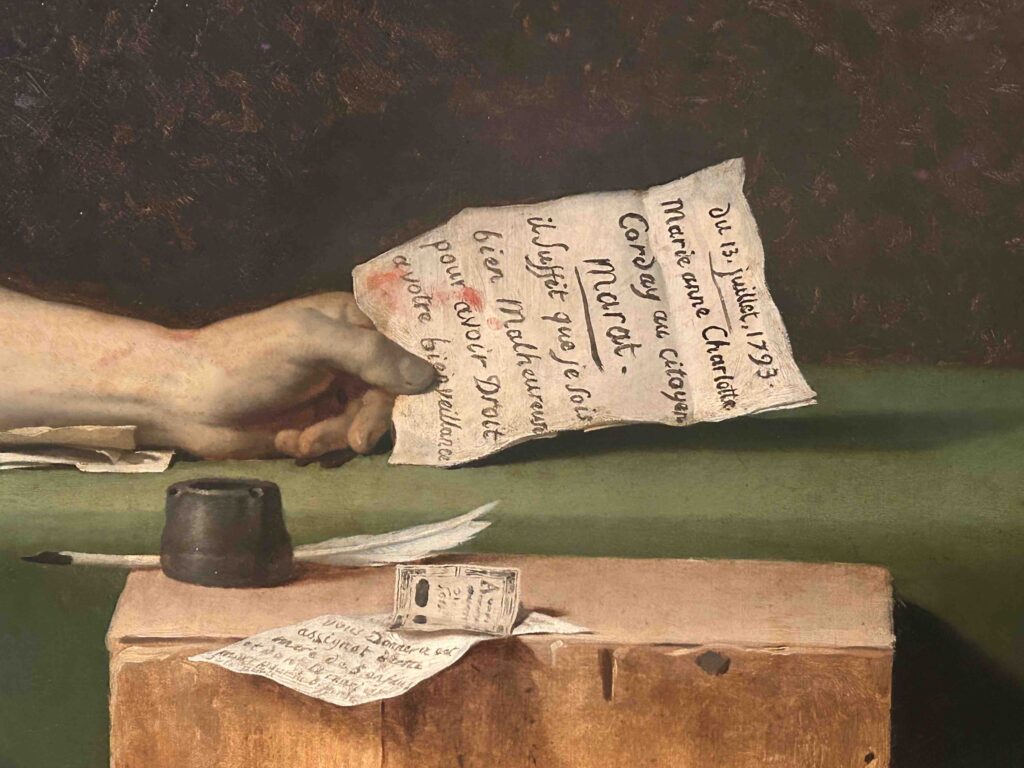

The highlight of the show is David’s 1793 The Death of Marat, which is usually in Brussels. In fact, the exhibition features three full-size near-identical canvases of the subject, but the original is simply, straightforwardly stunning, and on its own worth the trip across the channel.

What this painting, and the show as a whole, made me understand better than I have previously is how profoundly political an artist David was, and indeed how close he was to Robespierre. And it is David as a fiercely engaged figure that the curators suggest, without being didactic, makes him an artist not to be confined to the history books but to be understood as a singularly contemporary figure. I was convinced, and especially so later in the day after seeing a great deal of political art from the past few years.

Also here is the surviving fragment, below, of David’s six-by-ten metre canvas that was to commemorate the Tennis Court Oath of 20 June 1789. This is astonishing in a quite different way, and one can understand why, as the wall label notes,

David was haunted by the unfinished state of this painting celebrating the nation’s unity. He tried several times to finish it.

One other canvas that entranced me was the extraordinarily modern-looking (and unfinished) Portrait thought to be Marie Louise Josèphe Trudaine, below, about 1791-92. Her enigmatic features, the astonishing highly worked ground, and the powerful use of the Revolution’s red, white and blue held me transfixed.

Fortified by David and by what was amongst the finest bowls soupe a l’oignon gratinée that I have ever eaten, I ventured to the other side of the Rue de Rivoli to enter the new premises of the Fondation Cartier. As I pulled up my ticket on my phone, the young man on the door warned me that, ‘This is not the entrance to the Louvre, monsieur’. Had my French been better I would have responded that I had been going to contemporary art exhibitions since before not only he had been born, but probably his parents also.

Indeed I visited the 1984 exhibition of work by Lisa Milroy and Julien Opie that opened the original Fondation Cartier in Jouy-en-Josas, southwest of Paris. Forty years on, the collection has grown up and has now taken over an 1855 neo-classical edifice on the Place du Palais-Royal in the heart of the capital. Internally transformed by Jean Nouvel, this is a remarkable addition to the Parisian art world, and there is a good introduction to it from Catherine Slessor for the Guardian.

In charge of displays is the brilliant but, some would say, wayward Chris Dercon, now managing director of the Fondation Cartier following lively times at P.S.1 in New York, Tate Modern, then most notoriously at Berlin’s Volksbühne theatre, and France’s Réunion des Musées Nationaux; Nina Seagal’s New York Times profile [gift link] is essential reading.

Dercon has installed for the opening Exposition Générale, or General Exhibition (until 23 August), a display in four sections of hundreds of works, mostly from the foundation’s own collection. Eclectic is perhaps a polite word for a dizzying presentation of most of the art world’s recent and current darlings (although not Opie or Milroy).

Maybe it was my lunchtime wine, but I found it initially challenging and ultimately simply confusing. There was spectacle, certainly, although I found the internal spaces, which have floors that can move up and down, at times cramped and not especially congenial for looking at the art. There were things familiar, including a fine pairing of La Grande Vallée VI, 1984 by Joan Mitchell and Wonderful World Blossom, 2018, by Damien Hirst, below, but so, so much that I was encountering for the first time – and without much to help me get my bearings.

Five minutes walk away is another central Paris vanity home for a major fashion house collection, the Bourse de Commerce, owned by, and one home for, the Pinault Collection. Occupying this until 19 January is Minimal, a show that I simply loved. I don’t think it was just that my head was clearer after a brief chilly walk, although I recognise that my tastes are increasingly uninterested by the whirr and buzz and insistence of so much contemporary art. This is a show of minimalist work that respects and quietly revels in just the opposite:

Characterized by an economy of means, pared-down aesthetics, and a reconsideration of the artwork’s placement in relation to the viewer, artists across Asia, Europe, North and South America challenged traditional methods of display. This approach invited a more direct, bodily interaction with the art, integrating the viewer and the environment into the artwork itself. While these transformations unfolded in distinct ways across different regions, they shared a common drive to expand the relationship between artwork and audience.

The spacious display is a model of clarity; much of the work, which was both familiar and unfamiliar to me, has an immediate beauty; and while the categories for grouping the art, such as ‘Light’, ‘Materialism’, ‘Grid’, are to an extent arbitrary, as all such are, they make for rooms in which works echo and enhance each other in immensely productive ways.

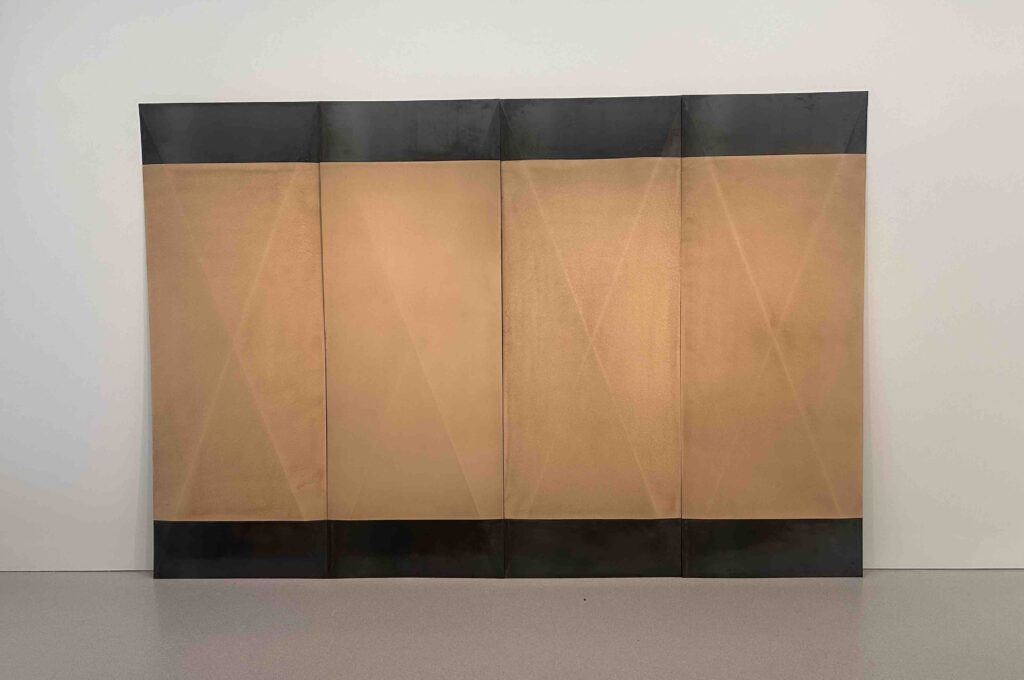

Some of my favourite artists are here, including Dan Flavin (above, first), Agnes Martin, Hans Haacke, and Dorothea Rockburne (Tropical Tan, 1967-68, above, second), who wonderfully is still alive in her mid-nineties. But the figure who provides the central display (header image), was new to me: the American sculptor and installation maker Meg Webster, who has five works that totally hold the glorious area beneath the building’s rotunda.

Lastly, a Metro across to the Palais de Tokyo. (Incidentally, there are so many up and down steps in the Parisian underground system that it must be impossible to negotiate as a disabled person.) For the cavernous spaces here, curator Naomi Beckwith, deputy director of New York’s Guggenheim Museum and organiser of Documenta in 2027, was invited to mount a show on a theme of her own choosing.

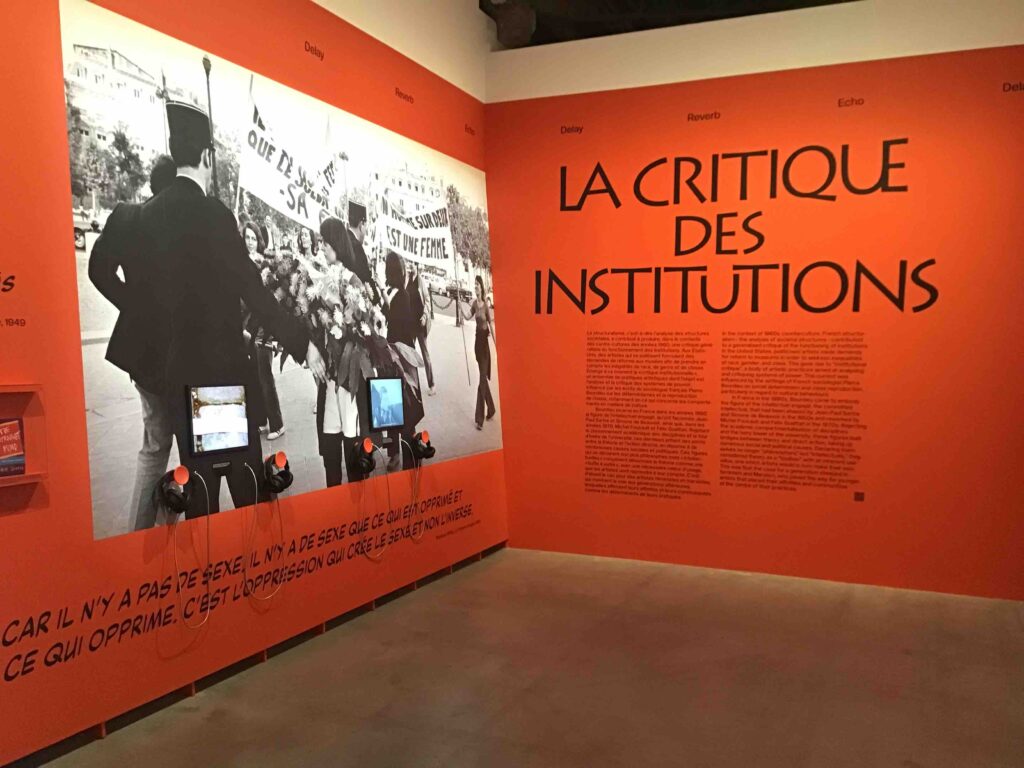

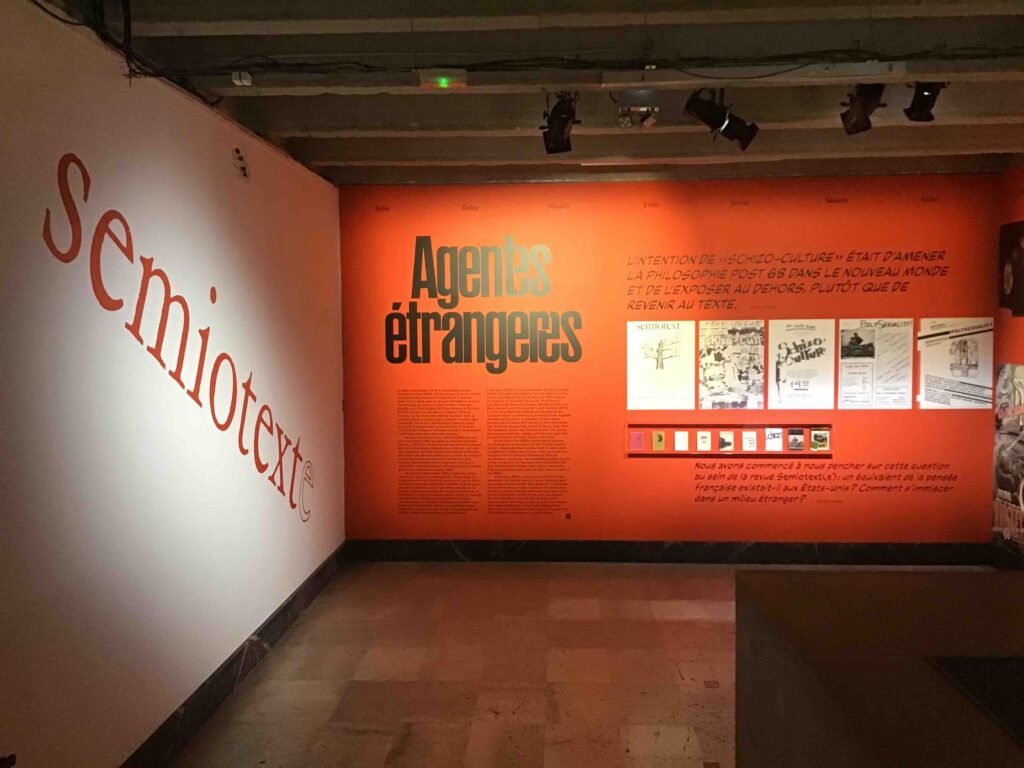

Echo Delay Reverb: American Art, Francophone Thought (until 15 February) is about the dialogue between post-war French theory and the critical response to it by artists working in the United States. With a far-from-specialist interest in Barthes, Foucault, Deleuze and Derrida, and having made a clutch of films about contemporary art, I felt I was probably fairly central to the (relatively small) target audience.

I was also keen to know more about the ideas of the other figures named in the publicity, inclkuding Suzanne and Aimé Césaire, Frantz Fanon, Édouard Glissant and Monique Witting. And while I knew some of the artists included such as Mark Dion (Between Voltaire and Poe, 2016, above), David Hammons, Cindy Sherman, Glenn Ligon and Fred Wilson, there were many, like Char Deré (Zone of Nonbeing, 2025, below) that were new to me. But honestly at the end of the day – and perhaps that didn’t help – I was overwhelmed and dispirited.

I so wish I could report differently, since the aspirations of the exhibition are exemplary [New York Times gift link], taking on central, urgent issues in cultural, postcolonial, feminist and gender studies. As the accompanying leaflet outlines:

By challenging social, aesthetic, and linguistic norms, [French thinkers] opened up new ways of seeing and acting… [The show] is the story of the circulation of ideas, their resonance and appropriation by several generations of artists across the Atlantic…

[T]he project is above all about relationships: relationships between art and thought, between the United States and France, between a foreign curator and a French institution,,, More than an outcome of research, it is an artistic, intellectual and curatorial adventure that looks to invent, spoeculate and to write history rather than to simply describe it.

Much like Minimal, the show is structured around themes, and each section is introduced by well-designed displays of ideas and biography, with quotations and video extracts:

These synopses are exemplary, but I often struggled to make the connections with the art that followed. Yet somehow there is a more fundamental problem, which is that this felt like a project in the wrong guise. Surely this should have been a book rather than a show? And indeed there is what looks like a fine catalogue, but for those of us who were struggling with Le Monde five decades back, it is only available in what appears to be somewhat forbidding French.

If you want more, there is a very good, detailed response to the show by Sinziana Ravini for Kunstkrittik, ‘How to lose a theorist in ten days’:

The overambitious approach, featuring sixty artists working from the 1970s to the present day, is interesting, but the thematically organised rooms appear isolated rather than integrated, making it difficult to get a sense of the ongoing dialogue between art and theory that the exhibition seeks to create. The overall impression? Everything is thought-through. Everything is important. But nothing feels urgent.

I really wanted to like this show, and I so wish I could be more enthusiastic. Then again, that morning I had been confronted with some of the world’s greatest political art, and perhaps anything was going to come up short after that. Walking back to the Metro I was rewarded by fine, seasonal sight of the city’s great symbol.

The richest analysis of David’s The Death of Marat that I know is that by TJ Clark in his monumental Farewell to an Idea: Episodes from a History of Modernism.

https://yalebooks.co.uk/book/9780300089103/farewell-to-an-idea/

I have gone back to this since Friday, and am slowly working through its dense and rewarding prose, but I was immediately struck by how YELLOW the book’s major reproduction is when compared with my memory and my photographs of the original.