OTD in early British television: 11 December 1937

John Wyver writes: the evening of Saturday 11 December 1937 featured an ambitious half-hour broadcast of act 3 of Verdi’s Aida given by the Matania Operatic Society. Opera was an important element of the transmissions from Alexandra Palace, although this broadcast under producer Dallas Bower, a little over a year into the service, was one of the first presentations of ‘grand’ opera.

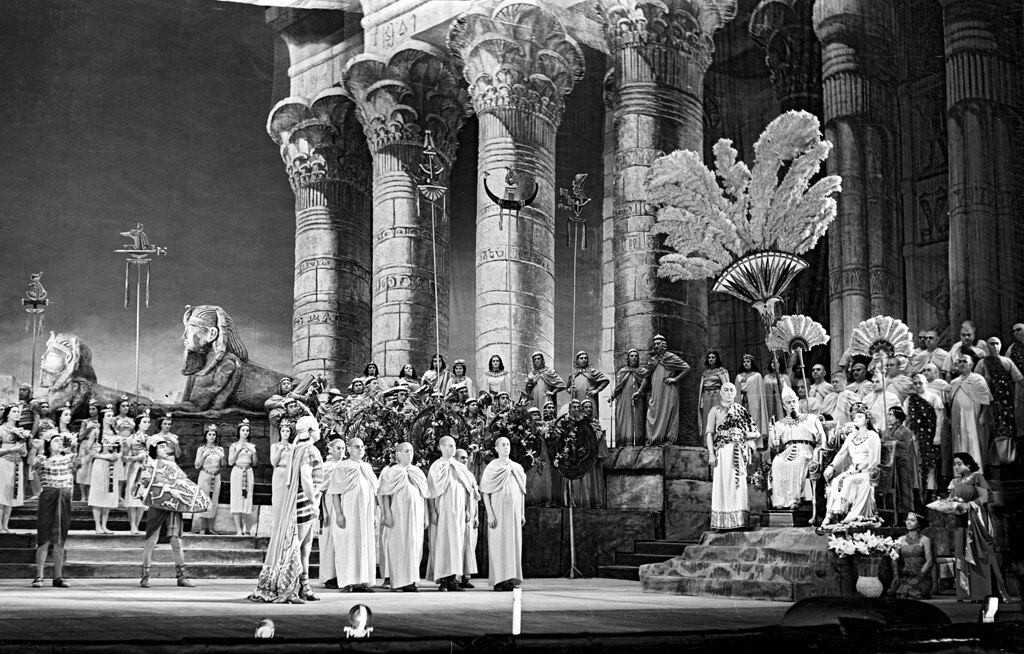

Gwaladys Garside (Amneris), Dorothy Stanton (Aida), Alec John (Radames) and Joseph Satariano (Amonasro), reputable singers all, led the cast of ten and the ever-versatile BBC Television Orchestra under Hyam (‘Bumps’) Greenbaum was augmented by seven additional players. As for the Matania Operatic Company, I’ve found not a single archival trace, so if anyone can give me a lead to who or what they were I would be most grateful. (For the avoidance of doubt, the image is NOT from the television broadcast, but rather – and simply because I liked it – of the Bolshoi Theatre Aida in 1957; more details below.)

As Alexandra Wilson chronicles in her fine book Opera in the Jazz Age: Cultural Politics in 1920s Britain, opera-going in late nineteenth- and early twentieth England was, ‘a genuinely popular and populist activity… [with] opera being performed more and more regularly beyond the West End, usually in English, to a socially mixed audience.’

But in the 1920s, musical theatre and the emerging ballet scene, as well the cinema, radio and sport were seen to be drawing audiences away from live opera, and increasingly the form became associated with elite contexts, most notably Covent Garden and, from the mid-1930s, Glyndebourne. Even so, Wilson argues, ‘[o]pera interacted in new and fruitful ways with precisely the forms of entertainment that might appear to have threatened its popularity, including films, popular music and middlebrow novels.’ This sense of opera as middlebrow and mainstream marked much of early television’s engagement.

At the end of just the second week of transmissions from AP, for example, with the service concerned to demonstrate its ambition and cultural credibility, Dallas Bower oversaw 25 minutes of excerpts from a new British opera. Thanks to the support of the British Music Drama Company, Albert Coates’ Pickwick (billed as Mr Pickwick by the BBC) was a week away from the Covent Garden stage. A celebrated conductor, including of contemporary British music, Coates composed seven operas among a body of compositions described by Groves Music Online as ‘technically proficient rather than imaginative.’

In the first months of the new service’s presentations of opera, the focus was on modestly-scaled English ballad operas. Producer Stephen Thomas explored the Englishness of English music in repertoire and artists that he knew from his earlier work at the Lyric Theatre, Hammersmith. A scene from his staging of Dr Arne’s dramatic pastoral Thomas and Sally, or The Sailor’s Return, can be seen in the BBC Television Demonstration Film (from which the following framgrabs come). Minimal action and basic characterisation play out in front of a crude backcloth, but Joan Collier, Colin Cunningham and noted baritone Dennis Noble are in fine voice.

Comic operas, ballad operas and operettas, both historical and original, featured regularly, and in the summer of 1937 Stephen Thomas extended his presentation of English eighteenth-century repertoire with Isaac Bickerstaffe’s Lionel and Clarissa and The Beggar’s Opera by John Gay. Gay’s perennially popular ballad opera was seen in a production adapted from one by Nigel Playfair, Thomas’ mentor, which had played to great acclaim at the Lyric, Hammersmith in the early 1920s.

Lionel Salter was a member of the BBC’s music staff in these years, and later head of television music, and at the end of his career he penned an invaluable account of the start of television opera. In two delightful articles for Opera magazine in 1977, he recorded his memories of working on opera broadcasts at AP. The singers were at one end of Studio A, before the cameras, while the orchestra was at the other, with an assistant conductor, who was sometimes himself, desperately attempting to pass the beat from the band to the performers.

‘This involved,’ Salter recalled, ‘ his darting from one side to another so as to be always in the singers’ eyelines (at all costs they should not be seen to turn their heads or eyes aside), leaping over cables and other obstacles and remembering camera positions so as not to get into shot – even (as I recall quiote vividly) conducting prone through a fireplace on occasion – all the while casting frantic glances over his shoulder to check unanimity with the conductor.’

As Salter also wrote, ‘The general feeling of mounting confidence [after the Coronation procession OB in May 1937] and increasing technical stability manifested itself operatically in the beginnings of a move out of ballad-opera and eighteenth-century chamber repertory into “proper opera”.’ In June 1937 Stephen Thomas mounted the garden scene from act 3 of Gounod’s Faust and then a 24-minute presentation of act 3 of Verdi’s La Traviata.

Dallas Bower, who along with Thomas was the other AP producer committed to opera, contributed Aida, before early on in 1938 organising one of early television’s folies de grandeur, a presentation of the whole of act 2 of Wagner’s Tristan and Isolde. But that is a tale that will have to wait for its own thread.

Header image: A scene from Giuseppe Verdi’s Aida opera. The USSR Bolshoi Theater (currently the State Academic Opera and Ballet Theater of Russia); RIA Novosti archive, image #855361 / Boris Riabinin / CC-BY-SA 3.0, CC BY-SA 3.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0, via Wikimedia Commons.

Leave a Reply