OTD in early British television: 22 February 1933

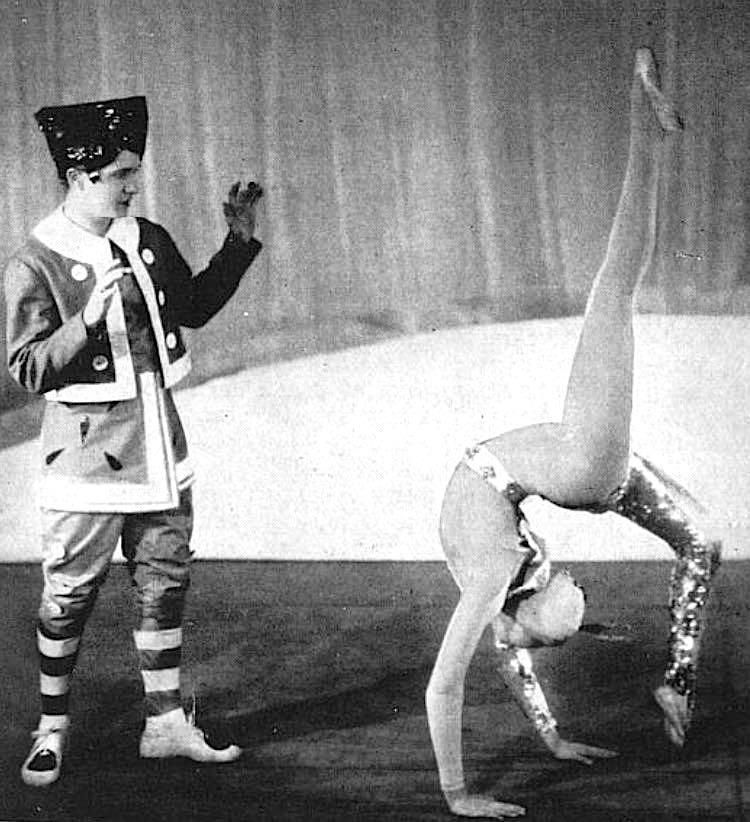

John Wyver writes: Today’s post is a melancholy little tale of a short, vibrant life in which early television played just a small part. The subject is dancer and acrobat Laurie Devine (above, right), who appeared performing ‘various dances’ on the late-night half-hour 30-line transmission from Studio BB at Broadcasting House on Wednesday 22 February 1933.

That Wednesday night was one of at least 40 documented appearances by Ms Devine on 30-line television, on occasions dancing with her brother Tom, and with a final bow on 4 September 1935. When she returned to work in her native Australia in August of the following year, she claimed ‘to have taken part in more television broadcasts than anyone else in the world’. Less than four months later, however, having had to withdraw from a hit revue in Sydney, she was dead from pneumonia.

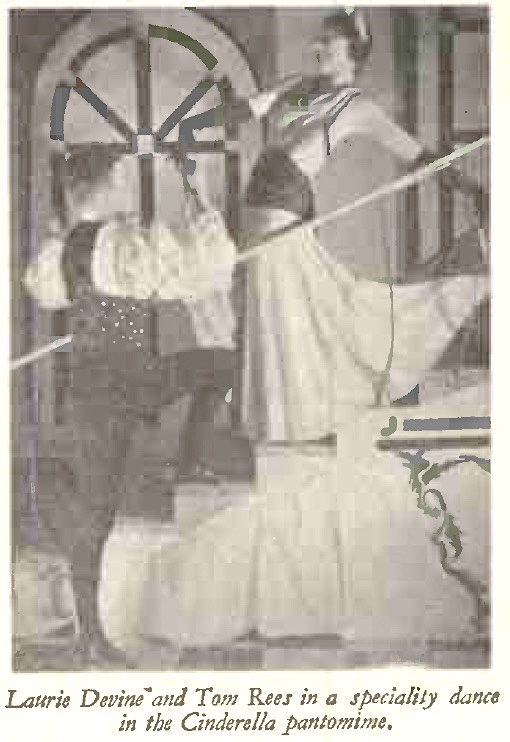

Laurie (sometimes “Lauri”) Devine was the daughter of Australian vaudeville and circus performer Tom Rees, and began her career aas a contortionist. By 1916 she was appearing on stage in London and a decade later was a celebrated cabaret and revue star, often performing with her brother Tom, who often took the family name of Rees. In 1933, she and Tom co-wrote a radio play Stardust and Sawdust, about circus life which was produced for the National Programme in May that year.

She first made an impact in Charles Cochran’s 1925 revue On With the Dance, which was scripted by Noel Coward, and three years later she was headlining Cochran and Coward’s This Year of Grace, a show that Alan Bott for The Sphere hailed as ‘superlative’. The critic was especially taken with one number:

I liked best of all the scene called ‘Dance Little Lady’ [below], in which Lauri Devine appears as a modern young thing swaying in the hard, jazz-mechanical, lifelessly ecstatic fashion of the mushroom nightclubs until she emerges into a revolving group of mirthless automatons wearing Mr. Oliver Messels’s masks of vacant grotesquerie. It is brilliant as satire and brilliant fantasy.

Here she is in another number from the same revue, in this case as the Rhinemaiden Lorelei:

Laurie Devine was noted for her acrobatic and contortionist dancing, and also for performing with grotesque masks, and she carried both features across to her work for television, as can be seen from the remarkable BBC publicity photograph below, which is dated 1932. Framed here by the stanhds of photoelectric cells that picked up reflections of the scanning beam while the performer was in darkness, the bold lines of both the dancer’s body and headgear would have registered well in the low-definition images of the time.

Her first appearance was in August 1932, with ‘interpretations of Italian, Russian and Central European dances’, and she was featured once each month for the rest of the year. In December she took the role of ‘Eastern dancer’ in the 30-line pantomime Dick Whittington. In 1933 she continued to appear regularly; one turn in March that year saw her dancing in masks as Josephine Baker and Greta Garbo. At Christmas both she and Tom had roles in the next panto, Cinderella.

In the March 1934 number of Television, producer Eustace Robb gave a detailed account of collaborating with Laurie Devine on a dance created especially for the screen:

In arranging an entirely original dance, which was being performed by Laurie Devine by television for the first time, I planned the choreography of the dance to introduce her miming in the close-up position.

My reason for this was that, as she was dressed in eighteenth-century costume of the most extravagant period, and was wearing a magnificent white wig, complete with a sailing ship perched on the top of her head – as in the true manner of the bright young things of those days – I wanted the audience to get a good view of these details and of her expression before showing the entire figure with less detail in the long-shot.

With the beginning of her dance she is faded into view – through a caption in the oval form of a dressing table mirror – showing her with small hand movements, powdering and patching her face, and we fade out as she is seen expecting the arrival of her beau. This completes the first section of the number.

We now fade it for a few seconds to the outlines of a window, and as the window fades it gives place to the now distant figure of the dancer in the full splendour of her hoops and draperies. Majestically she sails down the steps, which have now miraculously appeared – placed in position during the fade – to dance the pompous measure of the Pavane before her imaginary beau, and as the music moves from slow measure to quick, with frightened little runs the dancer is seen to fly this way and that until she escapes from our view and her imaginary lover, and the studio is faded out.

Robb’s description gives a strong sense of the complexity and ambition achieved by the 30-line service, as well as the versatility that the studio demanded of performers like Devine. She continued to appear on a more or less monthly basis throughout 1934 and 1935, until the end of the service in September that year.

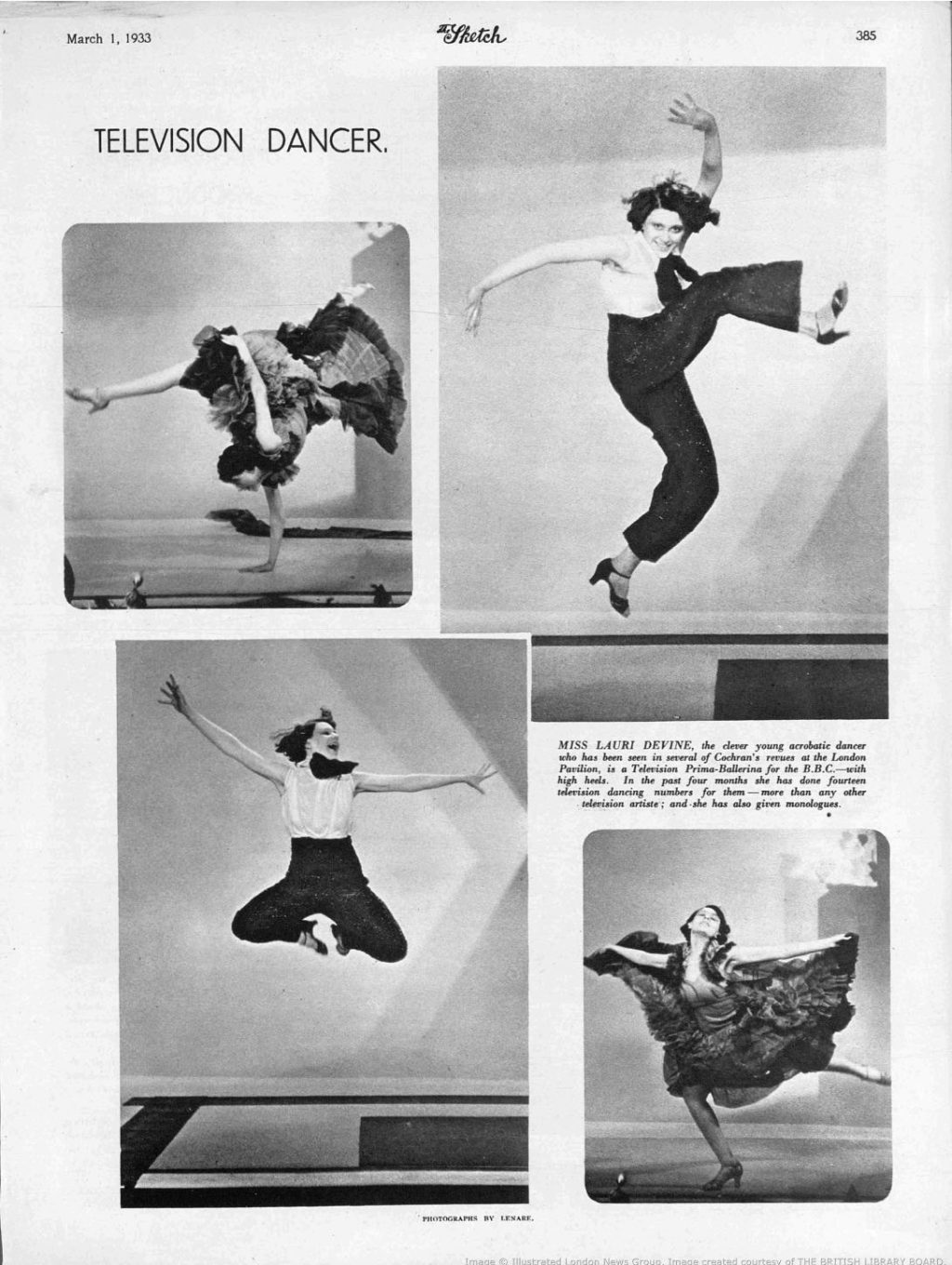

Here’s one final image: a page of photographs by the photographer Lenare from The Sketch, 1 March 1933. (More of society photographer Lenare’s work can be found in the collections of the National Portrait Gallery and the V&A; there’s also a delightful LRB review by Emma Tennant of a book about his work.)

The text reads:

MISS LAURI DEVINE, the clever young acrobatic dancer who has been seen in several of Cochran’s revues at the London Pavilion, is a Television Prima-Ballerina for the B.B.C. – with high heels. In the past four months she has done fourteen television dancing numbers for them – more than any other telerision artiste; and she has also given monologues.

Early in 1936 she must have decided to return to Australia, and sailed on the SS Moreton Bay, landing in Melbourne in August. On her arrival, she spoke with the Shepparton Advertiser (11 August 1936):

Describing a comic make-up which was necessary for television work. Miss Devine said that black and white formed the central colour scheme for appearances. Eyes and lips were blackened, the face painted ‘dead’-white, then lines of blue were placed down the nose, while all dancing had to be modified, and no high kicking was allowed, because of the restricted size of the projection screen. The black has since been modified to blue on the lips and round the eyes.

Before Christmas, following three months suffering from pneumonia, her death was announced as, in the words of Everyones magazine ‘a tragedy of poignant interest’.

Leave a Reply