OTD in early British television: 23 May 1939

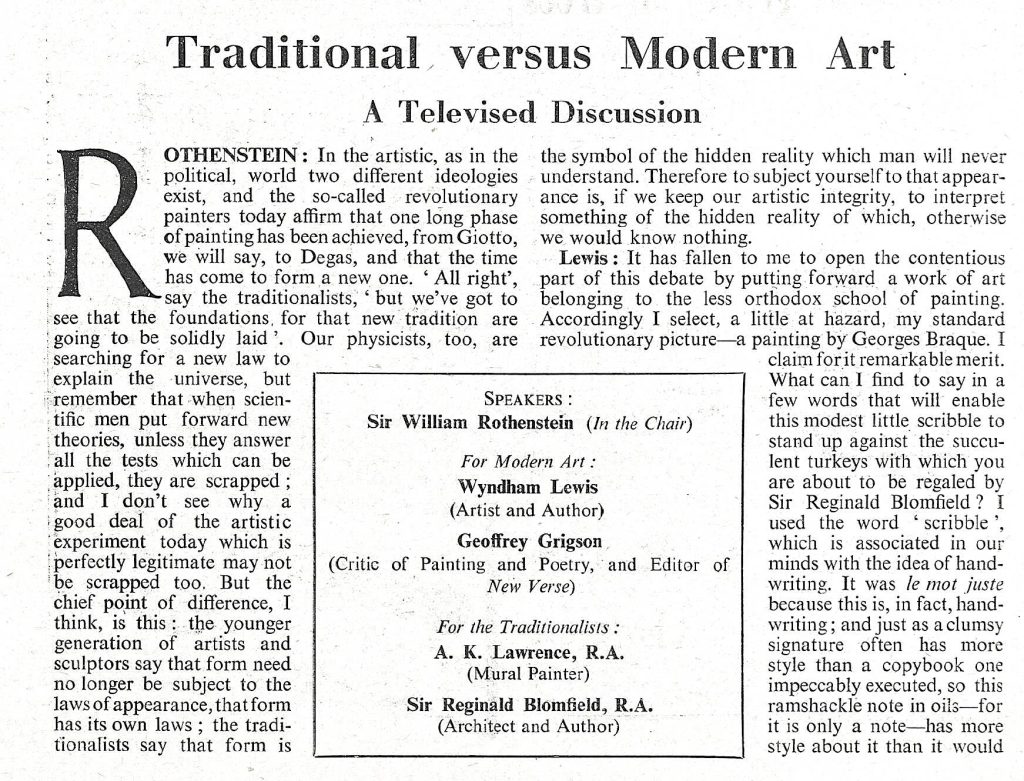

John Wyver writes: Television’s main offering on Tuesday 23 May 1939 was a 45-minute studio debate titled simply Modern Art. As the billing detailed, ‘Sir William Rothenstein took the chair. Mr Wyndham Lewis and Mr Geoffrey Grigson championed ‘unconventional’ modern art and Mr Reginald Blomfield and Mr A.K. Lawrence attacked it and put forward ‘conventional’ modern art.’

By this point in his late sixties, William Rothenstein was a distinguished portraitist and writer on art who from 1920 to 1935 was Principal of the Royal College of Art. Wyndham Lewis was a former enfant terrible and Vorticist, who had only recently returned to painting, while Geoffrey Grigson was known mostly as a poet, although he had exhibited in the 1936 London Surrealist Exhibition.

Reginald Blomfield was a prolific architect, architectural historian and garden designer, and his confrere A.K. Lawrence was a fine figure painter and muralist, as well as a stalwart of the Royal Academy. From this distance, you would have to say that the ‘moderns’ fielded the stronger team.

As can be seen from the photograph, the studio set-up allowed a range of paintings, prints and photographs to be displayed on a kind of magazine rack in front of the speakers (De Chirico’s ‘Death of a Spirit’ is visible.) Among the reproductions shown were artworks by Van Gogh, Cezanne, Picasso, Miro, Magritte and Paul Nash, along with a number of representational works.

More or less uniquely for a pre-war television broadcast, The Listener on 6 June carried a full transcript of the discussion, across 6 pages, including illustrations of paintings by Braque, Brangwyn, Monnington, de Chirico, Paul Klee and Sir David Cameron (the originals of each of which had been displayed in the studio), and sculptures by Hamo Thornycroft (represented in the broadcast by a photograph) and Henry Moore’s ‘Figure’.

After some impeccably neutral words from the chair, Wyndham Lewis began with a forthright defence of a ‘ramshackle note in oils’ by Braque, in which, he claimed, ‘the objects consorting there have an organic existence within the four sides of the frame.’

In reply, Blomfield was rather more literal, worrying that a foreground jug was not standing properly on its base, before launching into a broader attack on the Modernists, Abstractionists and Surrealists and ‘the problems with which they deal are problems for the psychoanalyst and alienist and have no more relationship to art than a jig-saw puzzle.

Blomfield’s response to Braque was ‘The Poulterer’s Shop’ by Frank Brangwyn, which Lewis dismissed as

an advertisement from a Victorian cookery book… there is organisation, but it is of the poster variety. Everything is translated into terms of blob and blotch, coloured like a cheap Eastern carpet.

Lawrence’s riposte was a mammoth mural in St Stephen’s Hall at the Palace of Westminster of ‘The Parliamentary Union of Scotland’ by Walter Thomas Monnington. In later life Monnington embraced abstraction, but this is a precise and smooth realist rendering of an historical event. The painter, according to Lawrence, was

like any other genuine artist – that is to say, whose intellect in his servant and not his master – is not concerned with the attempts to impose a kind of pictorial Esperanto upon mankind.

At which point Grigson spoke eloquently about De Chirico’s ‘Death of a Spirit’:

It’s a romantic arrangement of deep and, I think, very virile colour – deep green and black, brown, orange. If you asked me what it meant – always rather a dangerous question – I should say it is probably a comment on materialism and on the less pleasant and the more insubstantial characteristics of the life surrounding us.

Blomfield next turned the guests’ attentions to sculpture, introducing Hamo Thornycroft’s figure of Cromwell that still stands next to Westminster Hall. Wyndham Lewis dismissed the scultor as ‘a photographer in stone, a very debased type of artist – he is hardly worthy of the name of artist at all.’ To which Blomfield pointed out that the statue was in bronze, not stone.

Lewis introduced a small carving by Henry Moore, which he claimed ‘displays an exquisite understanding of the problem of the object in space’, to which Blomfield, warming to his theme, replied that to him such abstract works

mean nothing at all. The only emotion they excite in me is disgust and contempt. When I look at these polished and rounded lumps of stone they might mean to me either a woman with no clothes on or a suet dumpling.

Seemingly attempting to take a little of the heat out of the exchanges, Grigson brought forward ‘a fairy-tale painting’, Paul Klee’s ‘The Face of a Market Place’, which prompted from Lawrence a lengthy disquisition on the nature of criticism before he admitted that he did not understand the language of the moderns. As he said,

Criticism cannot be directed at these experiments. They are lifeless, intellectual exercises, lacking genuine artistic impulse or feeling, and bear about as much relation to the great stream of art, as the Regent’s Canal does to the Mississippi.

At the close, Rothenstein offered some ameliorative words:

Two good things do not exclude one another… [but] the real difficulty which you who try to follow the problems of modern painting have is the difficulty of distinguishing between an artist who merely chooses a fashion… and an artist who put’s the whole of his integrity into his life’s work…

In conclusion, I should like to say one rather didactic thing: you cannot take shortcuts to the understanding of the more difficult phases of art… the more you know about the beauty of the face of the world and the secrets of the human heart th nearer you will get to the exposition of life itself, which is the business of all artists.

[OTD post no. 157]

Leave a Reply