OTD in early British television: 12 June 1935

John Wyver writes: As the 30-line service under producer Eustace Robb moved towards its final broadcasts in early September 1935, the offerings became increasingly eclectic and distinctive. On the evening of Wednesday 12 June 1935, a 55-minute transmission was billed as ‘A recital of folk songs and dances from India, Ceylon and Tibet’.

Along with the Sinhalese singer Surya Sena, assisted by Nelun Devi (already the joint subjects of an earlier OTD), this late-night programme also featured the only British television appearance by American dancer Ted Shawn and his all-male company.

Shawn worked from 1914 on with the choreographer Ruth St Denis, to whom he was married, and their personal and professional relationship lasted until the early 1930s. As Wikipedia details,

Together, Shawn and Ruth St. Denis established an eclectic grouping of dance techniques including ballet (done without shoes) and movement that focused less on rigidity and more on the freeing of the upper body.

To add to St. Denis’s mainly eastern influence, Shawn introduced elements of North African, Spanish, American and Amerindian dance, ushering in a new era of modern American dance. Breaking with European traditions, their choreography connected the physical and spiritual, often drawing from ancient, indigenous, and international sources.

In July 1933 Shawn’s new company of all-male dancers gave their first performance at a farm in Massachusetts that would become the site of the hugely significant Jacob’s Pillow Dance Festival. Wikipedia again:

Shawn produced some of his most innovate and controversial choreography to date with this company such as ‘Ponca Indian Dance’, ‘Sinhalese Devil Dance’, ‘Maori War Haka’, ‘Hopi Indian Eagle Dance’, ‘Dyak Spear Dances’, and ‘Kinetic Molpai’. Through these creative works Shawn showcased athletic and masculine movement that soon would gain popularity. The company performed in the United States and Canada, touring more than 750 cities, in addition to international success in London and Havana.

As Janet Rowson Davis noted in her foundational essay ‘Ballet on British television, 1932-1935’ (Dance Chronicle 7:3, 1984-85), the company performed the dances “known properly as ‘Invocation to the Thunderbird’, ‘Ponca Indian Dance’, ‘Fetish’, ‘Turkey in the Straw’, ‘Flamenco Dances’, and ‘Pioneers’ Dance’.”

All of which titles indicate the fundamental questions about cultural appropriation raised by Shawn’s legacy, as well as by the creations of Ruth St Denis. I return to this below, but first some further notes from Rowson Davis. She speculated that as the Shawn company appearance was not trailed in Radio Times, and not indicated by the programme title, it was arranged at the last minute:

[The company] had given three matinees at His Majesty’s Theatre, the third being on June 6. Then, according to [Shawn’s book] One Thousand and One Night Stands, he had an unscheduled week at the Apollo Theatre. This extra week would have offered just the sort of opportunity Eustace Robb would take, to engage a group which he had probably seen and realized would be good on television, and which he would other-wise have had to forego. The performance was late at night, after the company had already given matinee and evening performances in the theatre.

A review in the Daily Telegraph was enthusiastic:

Rarely have I seen so much movement crammed into a forty-five minute television transmission…. Red Indian and Cowboy dances by Ted Shawn and his American Male Ensemble came over well, despite the fact that the costumes had to be stripped of their spangles at the last moment to avoid glare in the television picture.

Rowson Davis further quoted Shawn’s memory:

Shawn himself recalled this television experience in Dance We Must, during a consideration of the future of dance. He described how weird it was to dance in the small darkened studio with thin black-and-white stripes being sent at them by the one revolving instrument [the scanner], which also created the impression that the floor was moving up and down.

And Barton Mumaw, one of the company’s star dancers and Shawn’s life partner from 1931 to 1948, also recorded the experience:

To know directions and keep one’s balance without barging into one another was a formidable test of our ‘group feeling’, and even alone, dancing the solo ‘Fetish’, it was strange and frightening to go into the air in a blinding light and try to gauge a safe and easy landing on an invisible floor. My first experience on the tube rather put me off.

The director-dramaturg Gaven Trinidad tackled questions of cultural appropriation by Shawn and Ruth St Denis in a rich and nuanced 2019 essay, ‘Celebrating historic milestones while critically understanding the past’, posted at Howlround Theatre Commons. His prompt was a 2018 exhibition entitled Dance We Must: Treasures from Jacob’s Pillow, 1906–1940 in Williamstown, Massachusetts, also reviewed here by Gia Kourlas for The New York Times. As Trinidad wrote:

some of the materials, particularly the costumes, were examples of cultural appropriation and white cultural imperialism of its time. The costumes were not simply worn, but were essential in helping create movement, stories, and representations of ideas and peoples that still populate many artistic spheres…

In the exhibition, [the curators] contextualized St. Denis and Shawn’s complicity in racism and colonialism in the earlier half of the twentieth century, when their cultural appropriation was not challenged but was considered politically radical and innovative by certain mainstream white American and European critics and audiences.

Which would have been the case for most of those among the London audiences in 1935, whether in the theatre or watching the 12 June 1935 broadcast. And that Shawn and his company were invited by Eustace Robb is one further indication of the producer’s deep commitment to modern dance in the early 1930s.

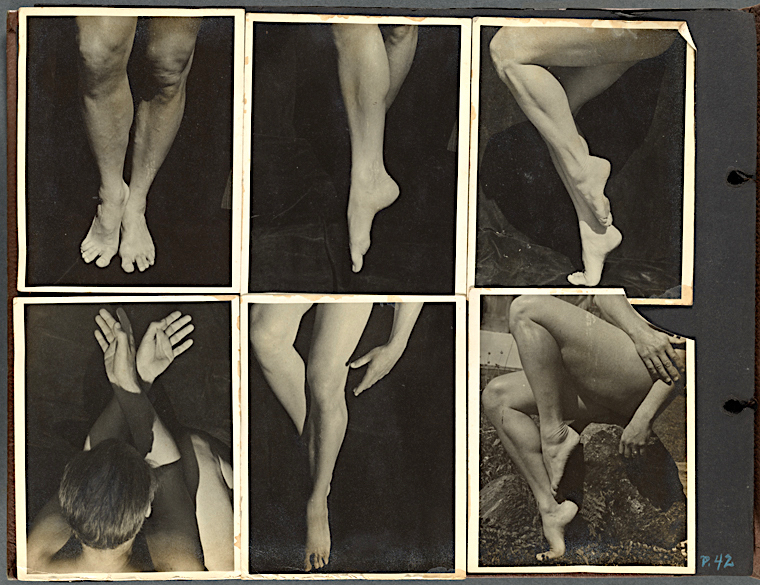

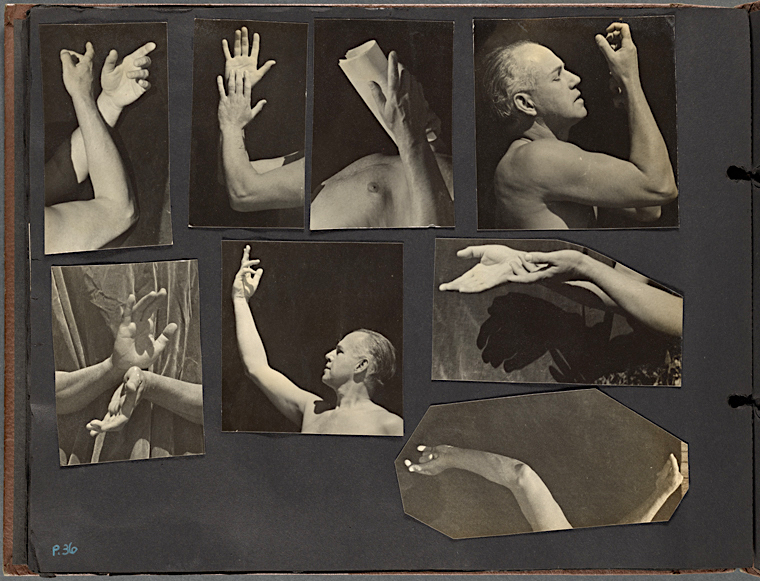

Header image: Five photograph studies of Ted Shawn’s legs and one of his hands; image in the text: Eight photographs of Ted Shawn’s arms and hands, Jerome Robbins Dance Division, The New York Public Library, The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1930 – 1939;

[OTD post no. 177; part of a long-running series leading up to the publication of my book Magic Rays of Light: The Early Years of Television in Britain in January 2026.]

An Edison film of Ruth St Denis, dancing under the name Ruth Dennis, is, I believe, the oldest film held by the BFI National Archive. It dates from around mid-July 1894.

Thanks, Luke – that’s not online, but I have found what appears to Ted Shawn and company filmed performing ‘Kinetic Molpai’ at Jacob’s Pillow in 1935, the year of their sole television appearance:

https://youtu.be/sqWjm7BHEkI?si=ECU1bF0h4nEc44ca