OTD in early British television – and more

John Wyver writes: Apologies for the blog’s month-long hiatus and the interruption of the daily ‘OTD in early British television’ posts. The last such post was on 25 September, and since then I have been immersed in a month-long process of proofing and indexing and checking the manuscript of Magic Rays of Light: The Early Years of British Television. All of that is now complete, the book goes to the printers next week, and I can re-boot the blog with renewed energy and focus.

Publication by Bloomsbury and the BFI is still scheduled for 8 January, and January will also see a season of screenings linked to the book at BFI Southbank; more details of that anon. I am also organising an international conference about interwar television in early July, and again I will be returning to that in future posts. Indeed, as we are just two months out from publication, I am going to refine the way that these posts will work from now on.

I still intend them to be daily, and for some of them to continue (with numbering) the ‘OTD’ formula that I established over the past year. But I will also use some of the posts to highlight related topics, including readings and events. And I intend to broaden the range of topics to take in some of my other interests: film, performance, the visual arts, archives, digital culture, books and more. So with reflections on stuff I’m watching and stuff I’m reading, the posts will be more eclectic, and in time almost certainly significantly so.

I hope the posts will continue to interest you, especially if you are one of the subscribers who receives them by e-mail. If you are not signed up, and this intrigues you, enter your e-mail address in the box to the right. And if you feel that this isn’t what you want in your In box, unsubscribing is completely straightforward.

Today, apart from noticing that yesterday was the 89th anniversary of the start of of the high definition television service from Alexandra Palace, I am pleased to highlight a richly interesting contribution to the online History of the BBC website by the peerless historian of the corporation, and author of the invaluable The BBC: A People’s History, David Hendy.

David’s delightful essay, The BBC as the Nation’s Clock, explores how the BBC became ‘the nation’s time-keeper’ over the past century, from the first broadcast of the chimes of Big Ben on New Year’s Eve, 1923 onwards. The text is complemented by a wealth of clips and images, and concludes with a question about today’s time of podcasts, on-demand streaming services, box-sets and live 24-hour news:

Is the traditional schedule dead – and with it broadcasting’s long, intimate connection with time?

Well, up to a point, but as David points out,

Perhaps the rhythms of radio and television are still not entirely uncoupled from the rhythms of our own domestic lives. When it’s Tuesday in The Archers, it’s also Tuesday in the real world: the fictional world of Ambridge moves in parallel with our own, across the week, through the year, down the generations.

And some prestige drama series, like Slow Horses on Apple+ and indeed the BBC’s own Riot Women, are currently rowing back from ‘dropping’ all in one go, and returning to the rhythm of weekly treats that we have to wait for.

When this happens we experience something of that delight in anticipation, that sense of occasion, we once enjoyed.

All of which suggests that, for a while longer at least, some of those decades-long ways through which the modern media have shaped our own sense of time – how we arrange our activities, how we move through the world, how we co-ordinate with our fellow beings – can still be discerned, if only in vague, rather ghostly form.

Time and Telecrime

Let me add a footnote to this from my researches for Magic Rays of Light, which links to last weekend’s shift back from daylight saving time to GMT. Television from Alexandra Palace between the wars did its bit to remind viewers of the shifts to and from GMT, including on Saturday 17 April 1937, when Put On Your Clocks was a brief feature with verses composed and read by Olga Katzin and a clockwork model by Peter Hood illustrating Daylight Saving.

Later in the year, on 3 October 1937, Put Your Clocks Back also featured Olga Katzin, this time accompanied by puppets given life by Ann Hogarth (later, creator of Muffin the Mule) and her producer-husband, Jan Bussell. And then on 9 April 1938, Olga Katzin was back again in Clock Summer In, this time with leftist journalist J.F. Horrabin, who was the host of the popular television series News Map.

A year later, the evening when the clocks again went forward featured an edition of the Telecrimes series. There were five pre-war productions in this occasional short-form series, which was the brainchild of insurance clerk Mileson Horton (whose Christian name was actually Denis), and which he developed from his weekly series of ‘Photocrimes’ magazine features.

Published since 1935 by Odhams Press in Weekly Illustrated, each column featured a dozen or so photographs arranged with actors in simple sets, plus a brief explanatory text. The aftermath of a crime was pictured and the reader was supposedly provided with sufficient information to identify the perpetrator. Extending the contemporary fascination with whodunits in this ‘golden age’ of detective fiction, the popular print series was syndicated in the United States and collected in two books.

Translated to television, the idea was conceived to make the most of the medium’s visual potential, although judging from the surviving script and camera plan of the fourth production, The Almost Perfect Murder produced by Stephen Harrison late in the evening of Saturday 15 April 1939, the two-set, four-camera presentation was penny-plain.

A survey of a crime scene by Scotland Yard’s stalwart Inspector Holt (played by J.B. Rowe) was followed by brief interrogations of suspects. Then, to the surprise of the local policeman, the actual murderer revealed himself by fleeing the scene. Holt ordered a train station arrest before a fade to black and a single character caption: ‘?’

Over this, the announcer said, ‘And now ladies and gentlemen, we ask you to make up your own minds, “how did Inspector Holt reach his conclusion?” We will give you the opportunity of studying the evidence for a few moments.’ The scene changed to the victim slumped across his desk before closing, as a recorded ticking was faded up on the soundtrack, on a shot of a clock and a calendar.

After which Holt explained that the crucial clue was that the murderer had not altered a clock with the arrival of British summer-time. And then, the television service did its public information duty by reminding those watching to put their own clocks forward one hour that night.

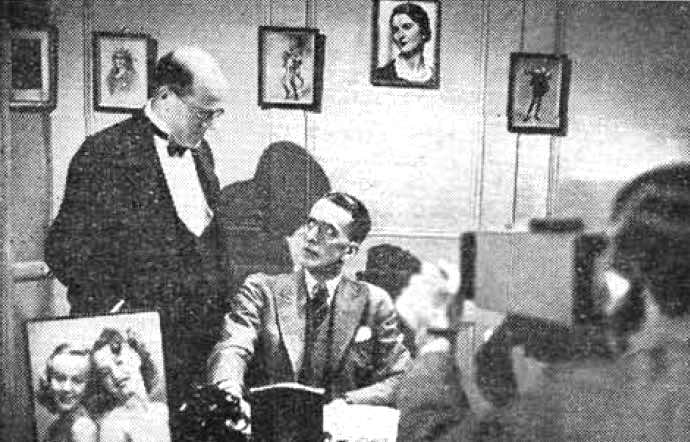

Image: J.B. Rowe as Inspector Holt (seated) in the Telecrime story Backstage Murder.

Leave a Reply