6th December 2025

John Wyver writes: My colleagues James Jordan and Eleni Liarou and I are a week or so away from finalising the programme for the symposium about the filmmaker Robert Vas to be held at Birkbeck, University of London, on Friday 27 March. We feel we have a rich programme already, but if anyone wishes to propose a further contribution, there is just one more week to put that forward.

In preparation, I have been watching the final film by Robert Vas that was screened during his lifetime, the 85-minute documentary Silver Spoon, broadcast on BBC2 on 2 January 1978, just over three months before his death on 10 April, at the age of 47. (Two other partially realised projects were completed by colleagues and broadcast after he died.) The film was spottily received by the critics, it was not repeated, and has hardly been seen since.

read more »

4th December 2025

John Wyver writes: I have now been contributing ‘On this day in early British television’ posts for more than a year now. Which means that in addition to amassing a total of 282 original entries, I am now encountering the days that I wrote for twelve months back. So 4 December has a post from 2024 that details the masque that H.D.C. Pepler and producer Stephen Thomas mounted based on Coleridge’s poem The Rime of the Ancient Mariner. This time round I have a new header image, of what I believe to have been the set (above), but the fairly text stands up pretty well:

One of the true eccentricities of performance presented from Alexandra Palace in the later 1930s was the cycle of masques staged by H.D.C. Pepler. On this day, 4 December 1937, mime and mask artist Pepler, working with producer Stephen Thomas, with whom he regularly collaborated, presented a masque based on Coleridge’s poem The Rime of the Ancient Mariner.

Working with an original score by Cyril Clarke, and with the poem read by Dennis Arundell, a cast of ten, including Pepler himself, and some in masks that Pepler had made, mimed and danced with rhythmic movements for a half-hour afternoon show.

You can carry on reading here.

read more »

3rd December 2025

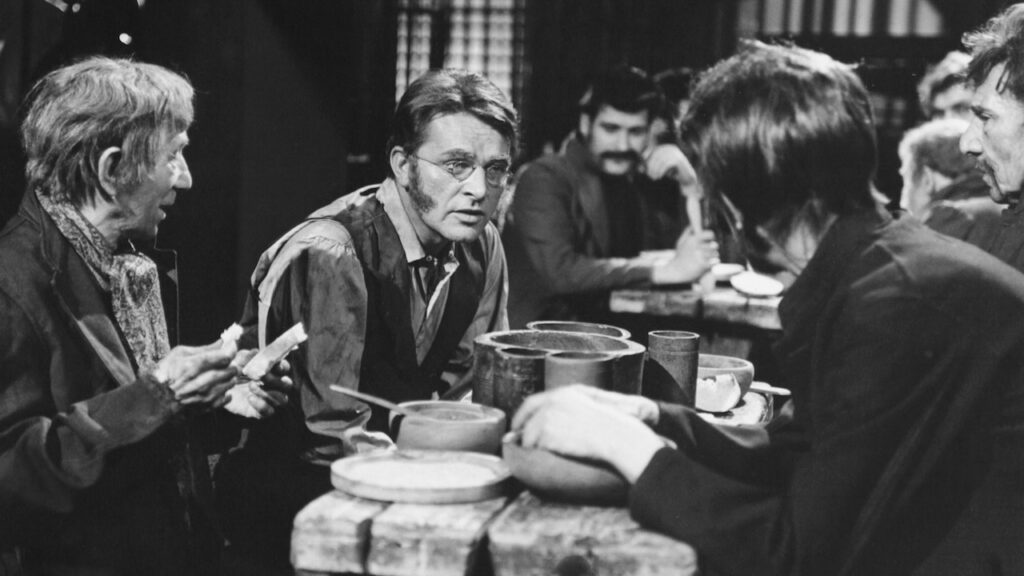

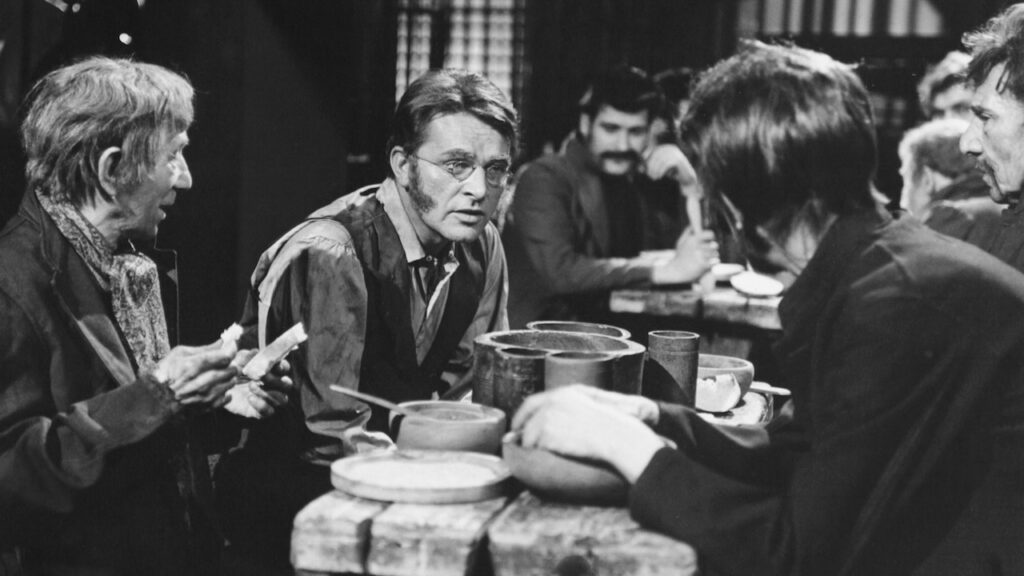

John Wyver writes: This coming Sunday, as part of BFI Southbank’s Muse of Fire: Richard Burton season, which kicked off last night, I am introducing a rare screening of John Osborne’s television play A Subject of Scandal and Concern, produced for the BBC in November 1960. This was recorded in April that year to 2-inch Ampex videotape and simultaneously tele-recorded to 16mm film, but we are projecting in NFT3 a very fine 35mm copy from the collection of the BFI National Archive.

Produced in the studio by Tony Richardson, this was made just a year or so after the release of the director’s film version of Osborne’s Look Back in Anger, in which Burton gave a compelling performance as Jimmy Porter. The television play, which was Osborne’s first for the medium, is a very different animal, being the true story of Victorian social reformer George Holyoake, was who was tried and sentenced to prison for blasphemy [correction made, as below].

I have been digging into the literature about Holyoake and Osborne, tracking down the press coverage of the production, and looking at the BBC production file in the Written Archives Centre at Caversham. Fortuitously it is one of those that has been previously vetted. So I think I have some interesting facts and reflections to share in my introduction, including a note about Burton’s fee of £1,000, which was regarded as astronomical at the time, and next week I plan to share some more of those here.

2nd December 2025

John Wyver writes: Just a reminder that BFI Members’ booking for the BFI Southbank Magic Rays of Light season opens today at midday. Booking for everyone else opens on Thursday at the same time.

You can book for the two programmes of documentaries (and a drama) about early television as well as for three screenings showcasing feature films that envisaged television in weird and wonderful ways before the BBC’s high definition service began at Alexandra Palace in November 1936. All of which is a celebration of the centenary of television and of the publication by Bloomsbury and the BFI on 8 January of my book, Magic Rays of Light: The Early Years of Television in Britain.

Tickets will also be available for the BFI Reuben Library Talk about the book on the evening of Monday 12 January. I’ll be in conversation with BFI curator Lisa Kerrigan, and I’m so pleased she agreed to take part. Here’s the blurb for that:

Magic Rays of Light (Bloomsbury) is a cultural history of television in Britain before the Second World War. John Wyver argues that, contrary to popular memory, this television was extensive, complex and innovative, as well as intimately entangled with the cinema, theatre, music and dance of the time. John Wyver will be in conversation with Lisa Kerrigan, Senior Curator Television, BFI National Archive.

30th November 2025

John Wyver writes: Another collection of articles and a video that have engaged me this week, embracing politics and the visual arts, melodrama, children’s television, PTA and Pynchon, neolithic monuments and a modernist lido, building Jerusalem in post-war Britain, the future of photography, close reading, and the hideousness of the Epstein elite.

Several of the links were suggested by friends and colleagues, for which thanks. I wasn’t sure what image to use this week, so I’ve simply chosen a favourite painting that I encountered in the Manchester Art Gallery earlier in the year: ‘New Street’, 1956, by Harry Kingsley. I am particularly fond of the television aerial.

• Surrealism against fascism: first up, a remarkable and essential essay by Naomi Klein for Equator about Gaza, fascism, Walter Benjamin, Surrealism, André Breton, Zohran Mamdani and much more:

We’re beginning to glimpse what fascism looks like amid the wreckage of history, with all its ironies and absurdities. But an urgent question remains unanswered: what, in that same wreckage, might antifascism look like? We cannot look to the past for easy answers, since the past has changed us in such fundamental ways. But we can look for clues – including to an antifascist movement of artists and philosophers in which Benjamin himself reserved a special kind of hope.

• Tightrope of hope: … and then the new LRB [£; limited free access] also has a rich essay about Surrealism and resistance to fascism, in this case by Hal Foster, who reviews with his characteristic thoughtfulness Surrealism and Anti-fascism: Anthology edited by Karin Althaus, Adrian Djukić, Ara H. Merjian, Matthias Mühling and Stephanie Weber.

read more »

28th November 2025

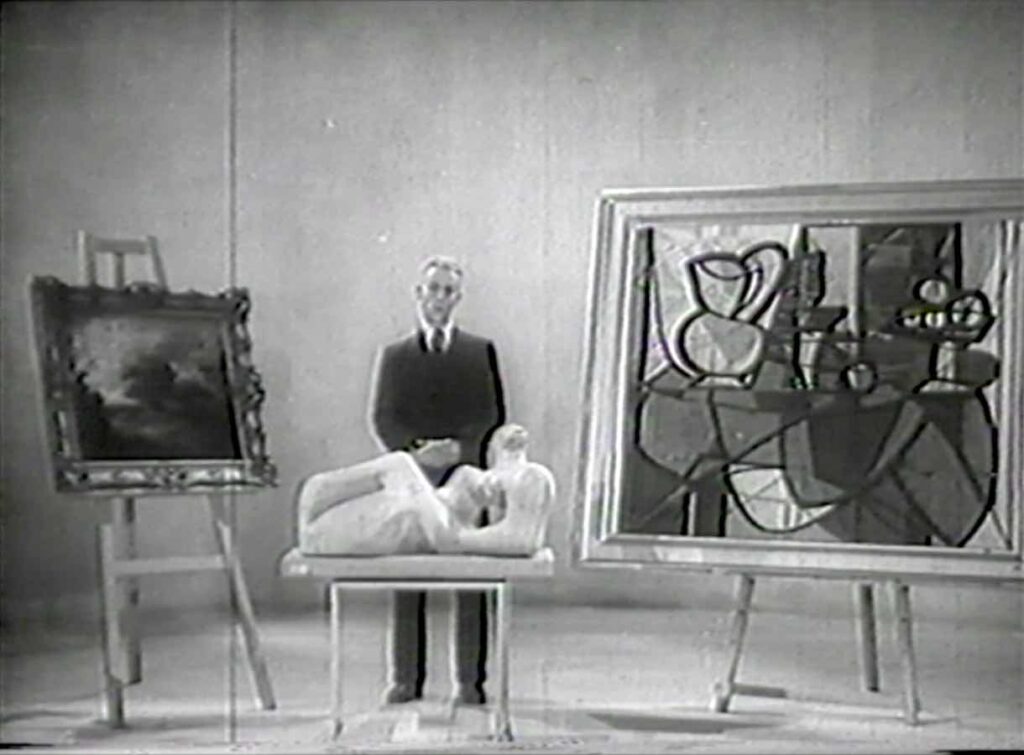

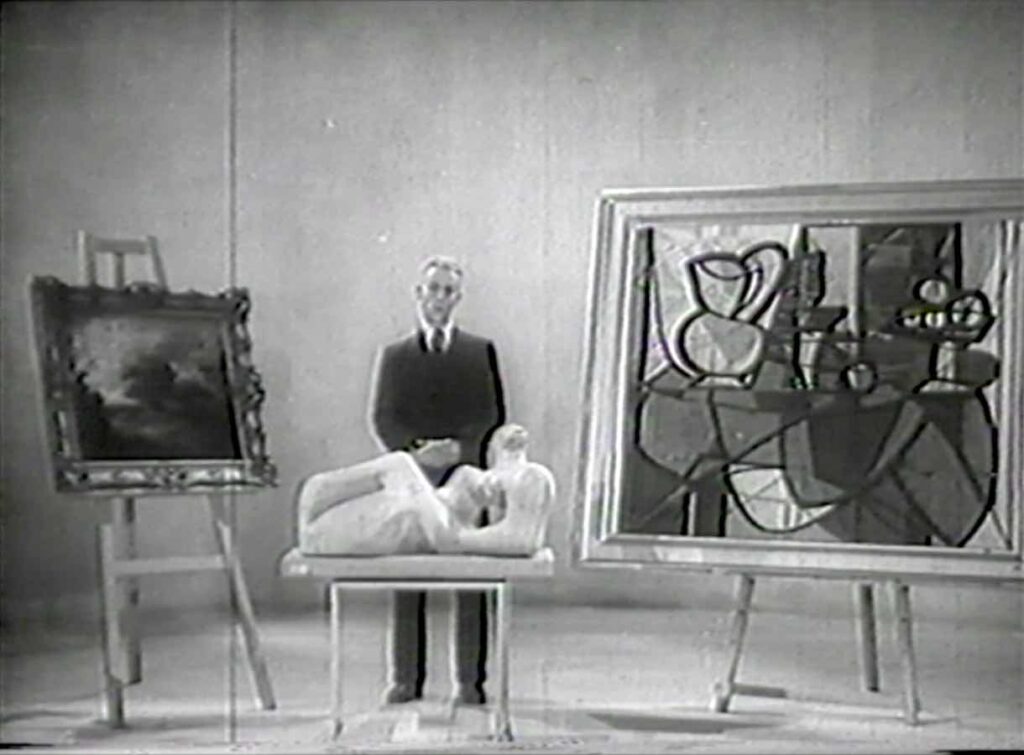

John Wyver writes: Between an appearance by the ventriloquist D’Anselmi and a short programme called The Accompanist Speaks, with pianist Ivor Newton, television’s main offering on the evening of Monday 28 November 1938 was the second edition (above) of the series Guest Night. Host A.G. Street, who was a noted author and farmer as well as a regular broadcaster, and producer Mary Adams gathered together five distinguished figures to discuss houses – ‘what they should look like inside and out, their arrangement in cities, and their place in the country’.

Assembled in a studio set of a well-appointed and comfortable drawing room were Merlin Minshall, Serge Chermayeff, Duncan Miller, John Gloag and Maxwell Fry. Discussion programmes featuring multiple participants were Adams’ innovation and still very much a novelty, and like almost all other Talks programmes of the time, this would have been carefully pre-scripted, here by Michael Spender (who may be the explorer and brother of poet Stephen and artist Humphrey).

read more »

27th November 2025

John Wyver writes: As noted earlier in the week, I have curated a screening season at BFI Southbank in January to tie in with the publication by Bloomsbury and the BFI of Magic Rays of Light: The Early Years of Television in Britain. Two of the programmes, to which I will contribute introductions, are of documentaries from the 1930s and ’40s, together with Jack Rosenthal’s drama about Alexandra Palace, The Fools on the Hill. I will return to the play in another post, and also to the three programmes of 1930s’ feature films, but here I want to highlight the documentaries that will have a rare outing on a big screen.

read more »

26th November 2025

John Wyver writes: ‘What’s language, mummy?’ a small boy asks actor Marina Vlady (above,. top) playing a waking Juliette Jeanson in Jean-Luc Godard’s Wild Palms, the world premiere of which was held at London’s ICA last night.

More accurately, the occasion was the first realisation of the late filmmaker’s ‘proposition’ for an adaptation of William Faulkner’s novel If I Forget Thee, Jerusalem, which was first published in 1939 as The Wild Palms. As Wikipedia says, ‘The book consists of two different stories, told in non-linear fashion in alternating chapters, which contain both parallels and contrasts.’

In his foundational 1967 study Richard Roud reported that Godard envisaged an interlaced showing of his films Made in USA (1966) and Two or Three Things That I Know About Her (1967), ‘first a reel of Made in USA, then a reel of Two or Three Things I Know About Her, then a reel of Made in USA, etc., just as Faulkner mixed two stories in The Wild Palms. That would be his adaptation of the novel.’

And thanks to the ICA cinema team, juggling complex projection and live subtitling, and to Michael Witt, season curator and author of Jean-Luc Godard’s Unmade and Abandoned Projects, newly published by Bloomsbury, the proposition was experienced for the first time, from fine 35mm prints, by a lucky few who filled ICA Cinema 1 for three revelatory hours.

(Michael Witt’s ICA season Jean-Luc Godard: Unmade and Abandoned continues on 9 December with Literary Adaptation 1: Guy de Maupassant, and then into the first months of 2026.)

read more »

25th November 2025

John Wyver writes: After a lengthy hiatus and posts concerned with other matters, we need to return our attention to the pre-war television schedules. So let’s look back 88 years to Thursday 25 November 1937 when the high definition service was just a year and three weeks old. At 15.01 that day, and again at 21.14, the schedule featured short outside broadcasts from the Elstree film studios. This was day three of a four-day visit, following earlier outings that autumn to Pinewood and Denham.

On Thursday afternoon film star Aileen Marson (above), standing in for a billed Elsa Lanchester, accompanied Leslie Mitchell and four pressmen on a tour round a quartet of sets to look at aspects of scenic design. According to the Programme-as-Broadcast form, they saw ‘a snow scene in Russia’, ‘a scene in a Persian market’, ‘an English street scene in pouring rain’, and ‘a London street scene in a fog’. That evening director Albert de Courville and actor Albert Burdon was interviewed by Freddie Grisewood against a background of the final shots of their comedy Oh Boy!.

read more »

24th November 2025

John Wyver writes: Exciting news just released by the British Film Institute: throughout January BFI Southbank has a season of documentaries and early feature films linked to the publication of my monograph Magic Rays of Light: The Early Years of Television in Britain, published by Bloomsbury and the BFI on 8 January.

As regulars here will know, later in the month, on 26 January, we celebrate the centenary of the first public presentation of what John Logie Baird called ‘true television’, at his laboratory above what is now Bar Italia in Frith Street.

Once the BFI brochure for January is out, I’ll post further details of the screening and dates, together with a note about my BFI Reuven Library talk on Monday 12 January, and also booking details. Meanwhile, here is the text from the BFI’s announcement at the end of last week:

… to celebrate the centenary of television, we present the short season Magic Rays of Light: Early Television which looks at the very earliest years of the medium. Curated by John Wyver, author of Magic Rays of Light: The Early Years of Television in Britain, the programme will include Television Arrives!, which features three documentaries made by the BBC to showcase pre-war television from Alexandra Palace and a fourth that marked the service re-opening in June 1946.

Other screenings include The Fools in the Hill (David Giles, 1986, BBC), Jack Rosenthal’s loving, comic recreation of the television service at Alexandra Palace as it prepared for opening night in November 1936, plus dramatic depictions of early television on film including Maurice Elvey’s British sci-fi thriller High Treason (1929), Will Hay playing a lightly disguised Lord Reith in Radio Parade of 1935 (Arthur B. Wood, 1934), the head of the broadcasting organisation NBG occupying an Art Deco premises clearly modelled on the BBC’s New Broadcasting House, and Adrian Brunel and Alfred Hitchcock’s Elstree Calling (1930), a lavish musical film designed as a British version of the Hollywood Revues in which Tommy Handley introduces an array of comedy and musical sketches, linked by acts presented in a television broadcast.