13th September 2025

John Wyver writes: Running at 56 minutes when it was first transmitted on Tuesday 13 September 1938, Felicity’s First Season by Charles Terrot has a claim to being the first full-length play written for television. The script, however, preserved on microfiche in the BBC archives, reveals it as theatrical comedy manqué, taking place in two rooms with just a short filmic bridge to indicate a change of scene to Scotland.

According to one critic, ‘the audience was amused and interested throughout’ by the mildly diverting tale of the rivalry for the hand of debutante between an impecunious journalist and a posh boy with a private plane. George More O’Ferrall was the producer entrusted with this fluff. ‘The result,’ the critic concluded, ‘was something between a stage play and a film – that is to say, good television entertainment.’

[OTD post no. 270; part of a long-running series leading up to the publication on 8 January 2026 of my book Magic Rays of Light: The Early Years of Television in Britain, which can now be pre-ordered from Bloomsbury here.]

12th September 2025

John Wyver writes: It’s Tuesday 12 September 1939, and we are a week and two days into the war. Television came off the air on the Friday before Neville Chamberlain’s declaration, but thanks to the excellent work of Andrew S. Martin in his monumental seven-volume Sound & Vision collection, published by Kaleidoscope, we know what the service was planning, at least in outline terms, through to 21 October.

For this Tuesday the service had in mind an OB from a West End theatre, which according to an earlier item by ‘The Scanner’ in Radio Times, was to be from the premiere of I Can Take It, starring Jessie Matthews (above) and her husband Sonnie Hale. Following a successful provincial tour, this had been scheduled to open tonight at the London Coliseum, but the war had led also to its cancellation.

The OB appears to have been planned along the lines of a previous one, in November 1938, from Under Your Hat at the Palace Theatre, which had Leslie Mitchell interviewing celebrity arrivals, interviewing the stars in their dressing rooms, and then transmitting early scenes from the show.

[OTD post no. 269; part of a long-running series leading up to the publication on 8 January 2026 of my book Magic Rays of Light: The Early Years of Television in Britain, which can now be pre-ordered from Bloomsbury here.]

11th September 2025

John Wyver writes: The evening of Wednesday 11 September 1935 saw the final 30-line broadcast from the BBC studio in Portland Place. There had been regular BBC transmissions since August 1932, but now following the Selsdon Report’s recommendation that a high definition service be started, these were discontinued with little fanfare or recognition.

The Selsdon Report on the future of television, published in January 1935, had been only modestly positive about the achievement of the more than 600 30-line presentations, recording that they had ‘a certain value to those interested in Television as an art, and possibly, but to a very minor extent, to those interested in it only as an entertainment.’

The decision of when to close down the transmissions was left to the newly constituted Television Advisory Committee (TAC), which in May acceded to the BBC’s wishes that they be given permission to do this. No public announcement from Selsdon, the TAC or indeed the BBC recognised the extraordinary journey made by the medium since the Baird company’s’s first simultaneous sound and vision broadcast from Long Acre on 31 March 1930.

read more »

10th September 2025

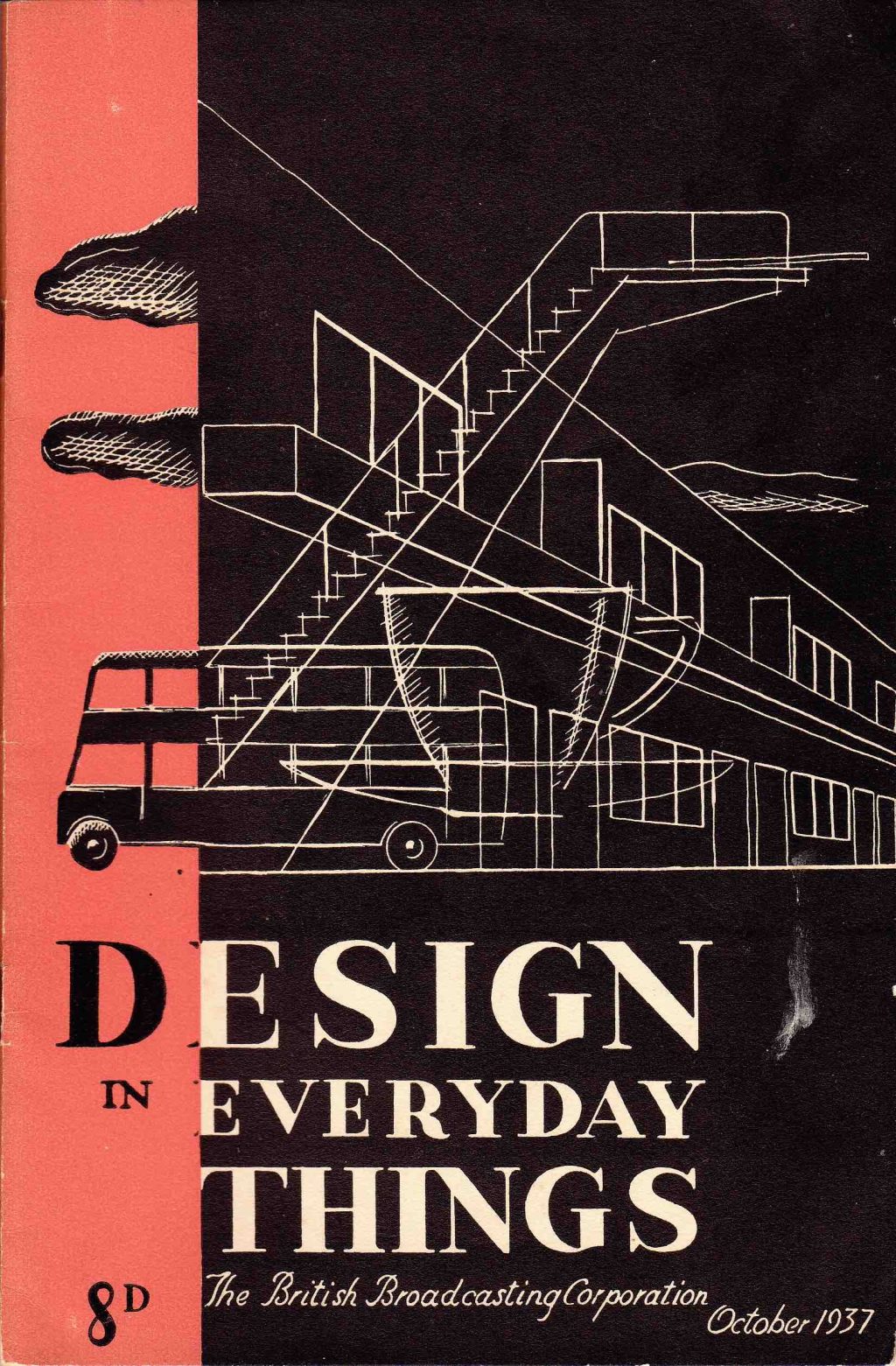

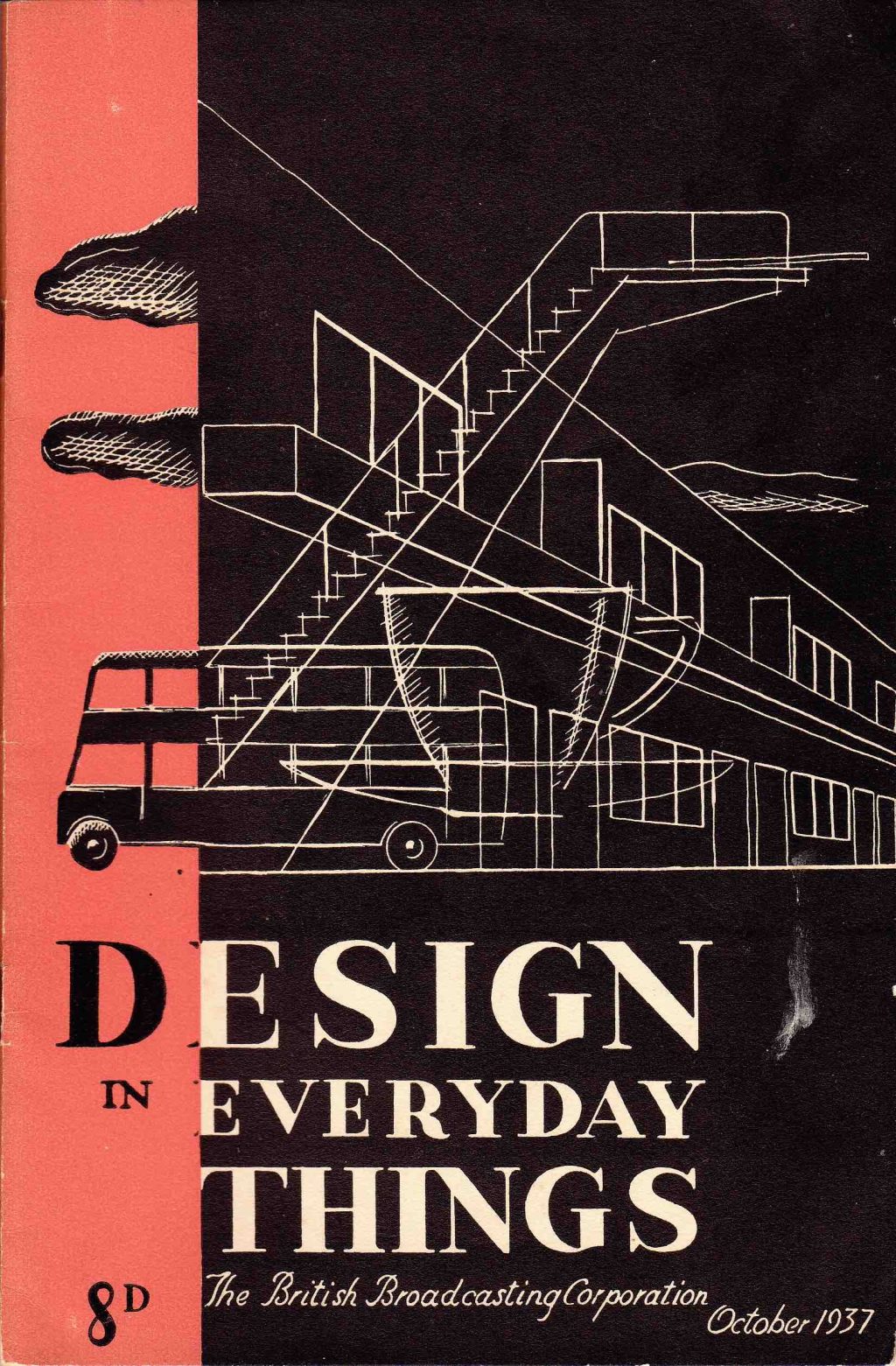

John Wyver writes: The evening schedule on Wednesday 10 September 1937 featured a 9-minute talk by Anthony Bertram titled What is Good Design? The producer was Mary Adams, and the PasB detailed that the broadcast was ‘illustrated by examples of household goods — china, irons, electric light fittings etc.’

As Mary Adams refllected in 1948:

To television may come credit for raising the general level of artistic appreciation, and reviving in the public a warmer climate of understanding. The detection of visual vulgarity by the viewer and his rejection of ugliness in everyday things, might be the beginning of such understanding.

Bertram was an art historian who was a confrere in this crusade. As a National Gallery lecturer, he had begun giving radio talks as early as September 1923, including The History and Meaning of Modern Painting in November that year. Strongly committed to modernism, he authored volumes on Picasso and Matisse, and in 1935 published a book with the Corbusian title of The House: A Machine for Living In.

read more »

9th September 2025

John Wyver writes: As promised yesterday, this is the fascinating text of Grace Wyndham Goldie’s LIstener column, ‘The Drama of Television’, dated 9 September 1936, with her first thoughts about the new medium. As the weekly’s radio drama critic, she had seen a demonstration during the Radiolympia broadcasts arranged ahead of the BBC’s ‘high definition’ service going on air on 2 November 1936.

What is television going to do to radio drama? Change It? Obviously. Revolutionise it? Probably. Kill it altogether? NO. You have only to watch the first television programme put out from Alexandra Palace for this to be perfectly, hearteningly clear.

I had been told that television was too raw for it to be worth bothering about yet; that the small size of the pictures made them difficult to watch and that the things seen flickered so much that a great strain was put upon the eyes. Most of this is nonsense.

read more »

8th September 2025

John Wyver writes: Today and tomorrow I want to highlight two early columns about television by the doyenne of pre-war critics, Grace Wyndham Goldie. And I want to do so by showcasing them in, as it were, reverse order, with the later one, from 8 September 1937 today, and more or less her first words about television, from 9 September 1936, tomorrow.

Tomorrow’s is concerned with first thoughts about the medium itself, whereas this one focuses on a particular production. Before this Wyndham Goldie was steeped in the theatre, having worked with the Liverpool Playhouse and written a book about its history, and in radio drama, writing for several years about the artform that debuted just before television.

read more »

7th September 2025

John Wyver writes: The Wednesday evening of 7 September 1938 featured a 18-minute talk by portraitist and muralist Edward Halliday titled Masterpieces on Your Walls. Using sixteen examples, he discussed ‘the advantages of modern colour reproductions which bring a wide variety of good pictures, old and new, within reach of all but the very poor.’

This was one of a number of programmes by which producer Mary Adams aimed to improve the visual sensibility of the nation (another will be the focus of Wednesday’s post). Halliday’s choice featured Botticelli’s ‘Primavera’, two Van Goghs and still lifes by Cezanne and Braque.

More recent work included a view of Muzzano by Carl [or Karl] Hofer, Paul Nash’s ‘Sussex Landscape’ (possibly ‘Landscape at Iden’, 1929, still available from Tate as a print), ‘Market Cross, Treboul’ (above), a very fine 1930 painting by Christopher Wood, and an ‘Antelope’ by John Skeaping, an artist who appeared in several of Adams’ inter-war broadcasts.

[OTD post no. 264; part of a long-running series leading up to the publication on 8 January 2026 of my book Magic Rays of Light: The Early Years of Television in Britain, which can now be pre-ordered from Bloomsbury here.]

6th September 2025

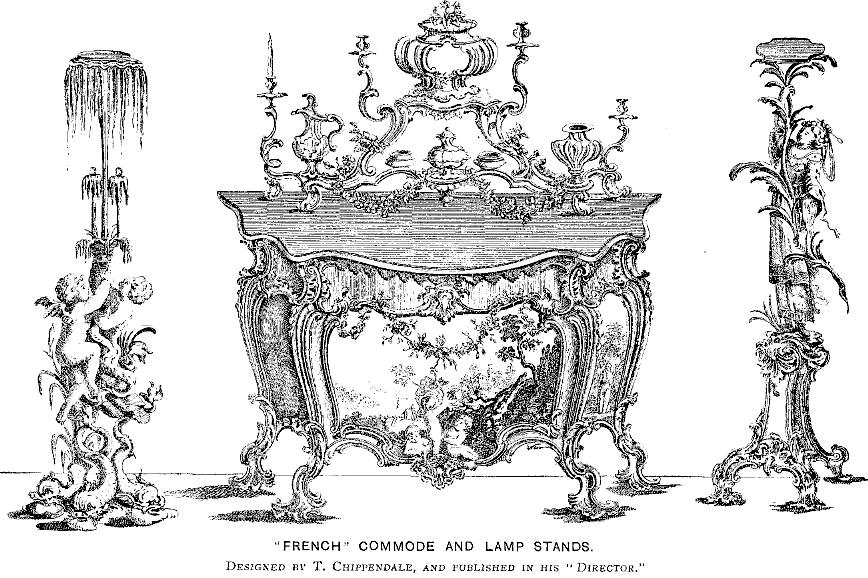

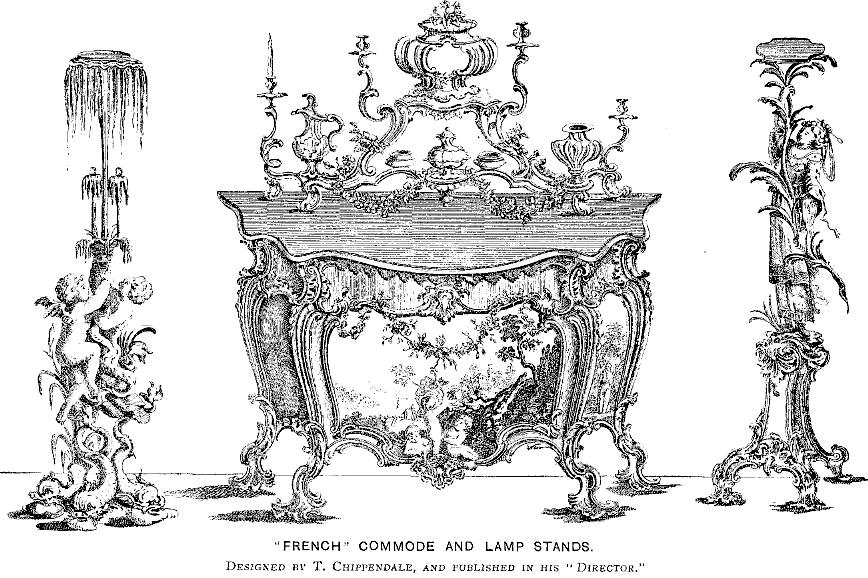

John Wyver writes: Wednesday 6 September 1933 saw the second performance on the 30-line service of Rokoko, a musical comedy programme selected from operettas by Leo Fall, Millocker and Emmerich Kalman. Henrik Ege contributed original dialogue and there were additional numbers by Mark Lubbock. Rokoko had been first played in late July, and it was one of the clearest examples so far of producer Eugene Robb’s ambition for the very basic portrait-format images of which the technology was so far capable.

Of the first broadcast, ‘Spectator’ wrote in Television:

Having secured the engagement of Naima Wifstrand, Sweden’s premier musical comedy actress, the producer determined to present her in an appropriate setting. So they all set to work, costumiers, carpenters, musical arrangers and dialogue writers and Rokoko, billed as the first television musical comedy programme, was the result. If the story was not altogether new, it was piquant, and the presentation was fresh and ingenious in detail.

The show opened with drawings depicting rococo design in its various forms, and the fussy elaboration of the costumes, the twists and curves of the figures and the furniture, emphasised in black and white, carried the looker straight back to the eighteenth century.

read more »

5th September 2025

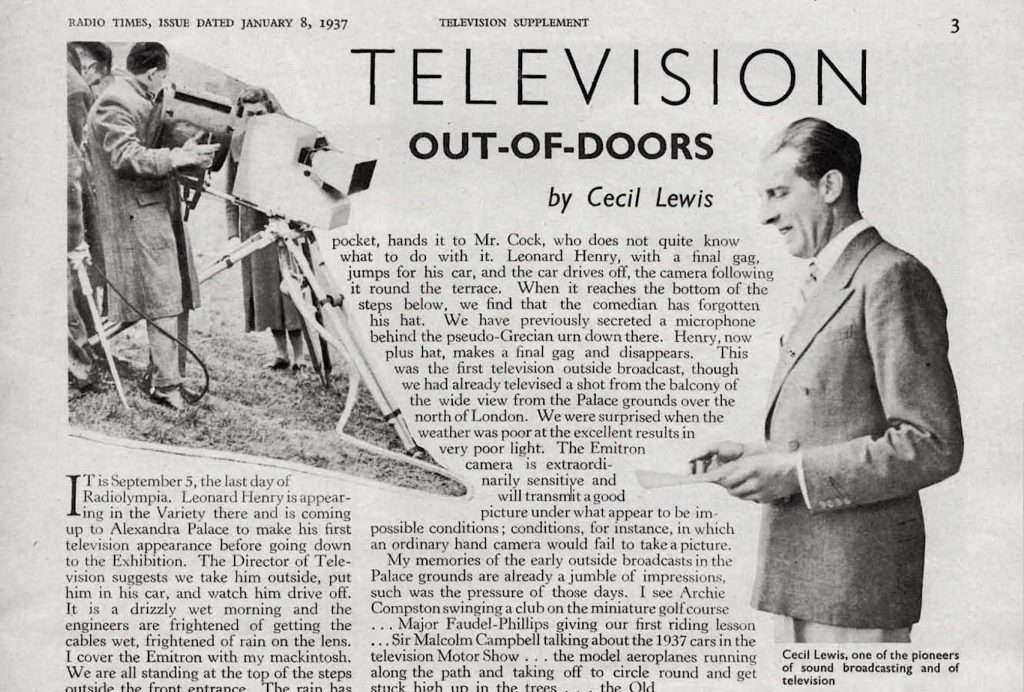

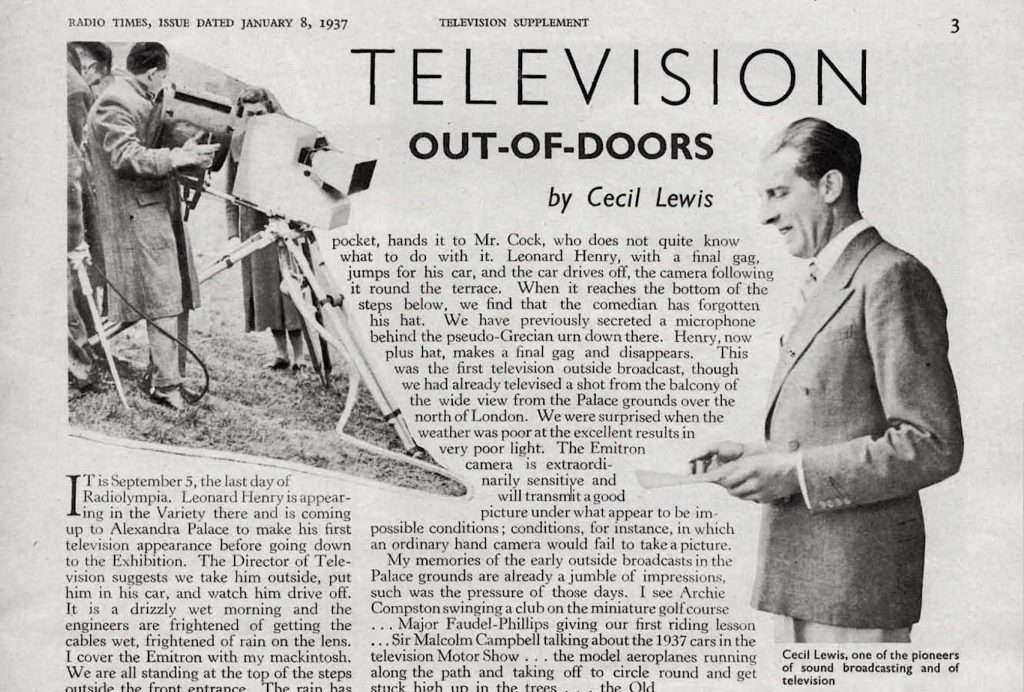

John Wyver writes: One last Radiolympia post, this time from the final day of the 1936 edition, Saturday 5 September. On this day producer Cecil Lewis, a radio pioneer and soon to be tempted to Hollywood to adapt his memoir of being a First World War fighter pilot, pulled together the first ‘local’ outside broadcast at just after midday. He recalled the occasion for Radio Times early in January 1937; this is his account.

It is September 5, the last day of Radiolympia. Leonard Henry is appearing in the Variety there and is coming up to Alexandra Palace to make his first television appearance before going down to the Exhibition. The Director of Television suggests we take him outside, put him in his car, and watch him drive off.

It is a drizzly wet morning and the engineers are frightened of getting the cables wet, frightened of rain on the lens. I cover the Emitron [camera] with my mackintosh. We are all standing at the top of the steps outside the front entrance. The rain has cleared and the sun comes out for a moment. Beginners’ luck.

The camera points up to the door of the building, and Leonard Henry comes out with Mr. Cock. They walk into close-up, and Leonard tells one or two stories, asks if he has passed out, and, producing a learner’s ‘ L ‘ from his pocket, hands it to Mr. Cock, who does not quite know what to do with it. Leonard Henry, with a final gag, jumps for his car, and the car drives off, the camera following it round the terrace.

read more »

4th September 2025

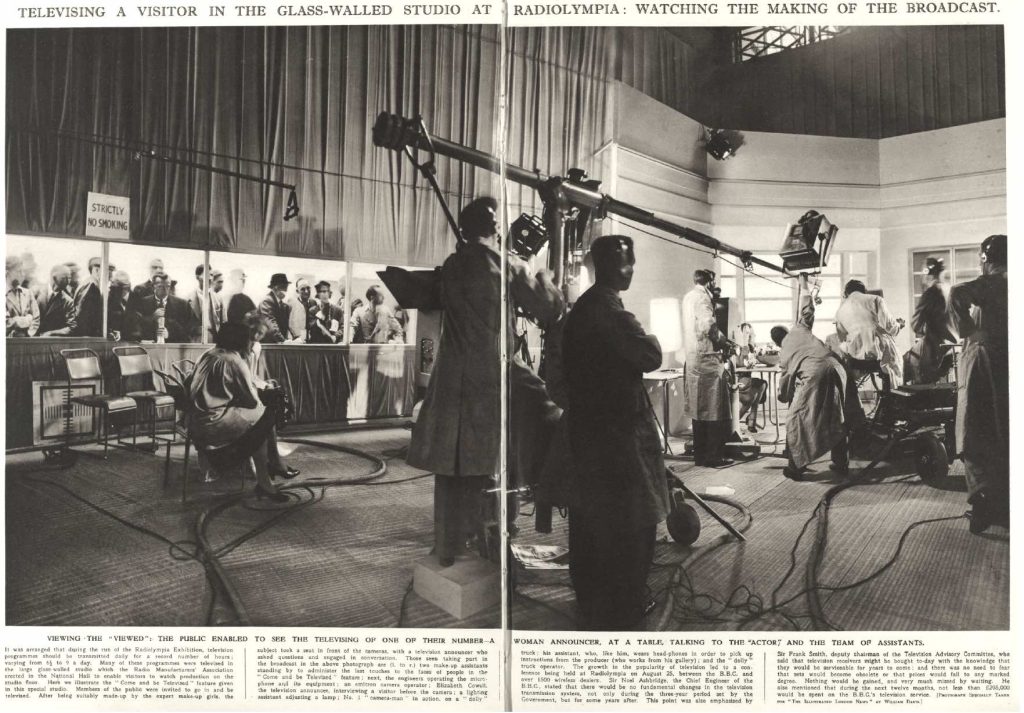

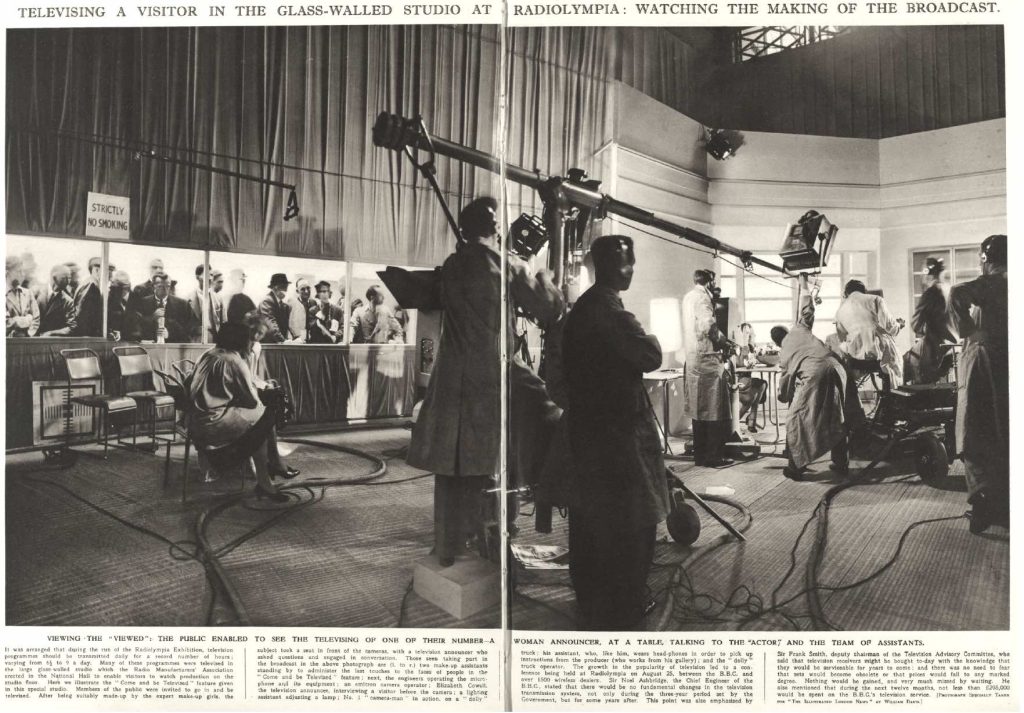

John Wyver writes: Perhaps this is a bit of a stretch but I want an excuse to return to 1938’s Radiolympia which closed ‘yesterday’. So I’m speculating that Sunday 4 September would have been the day when a crew dismantled the BBC’s elaborate Peter Bax-designed glass-walled temporary studio from which the BBC had been televising for some eight hours a day for the duration of the fair. Which gives me licence to feature the above truly remarkable photograph (taken by William Davis) from a spread in the Illustrated London News.

This is the only image I’ve seen which gives a clear sense of the windows, on the left, through which the public looked at the television operation, which were both praised for their transparent modernity. But this set-up was also criticised for excluding Radiolympia attendees from the shows, like Cabaret Cruise (see yesterday) that were broadcast from there.

read more »