OTD in early British television: 1 August 1930

John Wyver writes: In the weeks just after The Man with the Flower in his Mouth (see earlier post), John Logie Baird’s campaign to extend awareness of the potential of television next took to the stage of the London Coliseum. On Thursday 1 August 1930 Television as part of a variety bill was four nights into the first week of its engagement.

From the start of his work with television, Baird had been fascinated by its large-screen potential, and a roof-top display used for the press and others to see The Man with the Flower in His Mouth had been unveiled one evening a fortnight before the broadcast. ‘Setting for the show was perfect,’ reported Variety. ‘Screen was rigged against the skyline on roof of a pretty tall building, with diminutive electric signs playing below it, and a flaming cloud bank drawn up behind.’

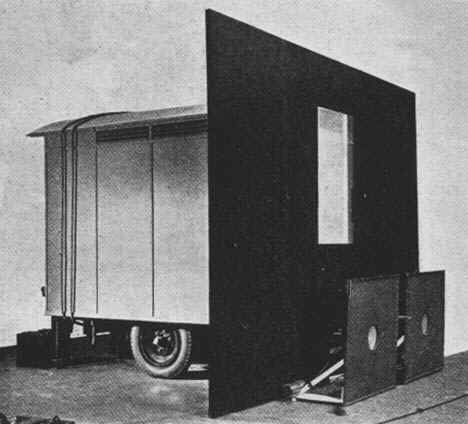

Following the presentation of The Man... to an audience of press and others, the cumbersome display was manoeuvred along from Long Acre to the cavernous theatre in St Martin’s Lane. As a crude screen mounted above two loudspeakers on one end of a black-painted caravan, television became a three-times-a-day novelty act on one of the capital’s most prestigious variety bills. In doing so, television followed early film which had been frequently featured in variety programmes.

What those watching The Man… saw was a matrix of 2,100 incandescent bulbs, organised in 30 vertical lines behind a ground glass screen. Each bulb was separately controlled, much like pixels in a digital display, so that they could switch off or on twelve and a half times a second. All of which, in addition to giving a brightly illuminated moving picture, generated an enormous amount of heat, to the extent that during the Pirandello there was a fear that the apparatus might melt. Fortunately, each turn at the Coliseum was scheduled to be around 10 minutes.

The bill at the Coliseum on the afternoon of Monday 28 July 1930 featured the Allison troupe of acrobatic tumblers, a pair of experts with the diabolo, and virtuoso mouth-organist Eddie Bowers. At a little after 2.15pm adventurer and filmmaker Ratcliffe Holmes stepped before the curtain to explain that this was to be the first time a paying audience witnessed television on a stage.

The tabs parted to reveal the seven-foot-high screen, looking a touch diminutive against the towering proscenium but apparently clearly visible throughout the house. ‘There is a rapid flicker of shadow-lines across [the screen] from right to left,’ described one journalist.

Suddenly the flicker, without stopping, seems to compose into a black-and-white, head-and-shoulder image of the person who is looking into the transmitting apparatus at the studio. It is possible to follow changes of expression… But the image is hardly distinct enough for easy recognition.

From the screen, although seated in Long Acre, Sydney Moseley extolled the wonders of television, actor Irene Vanbrugh said a few words, and retired boxer Billy Wells predicted (correctly) that Young Stribling would beat Phil Scott in the night’s big fight at Wimbledon. Songs followed, including one put over by the loyal Lulu Stanley, who deeply impressed a correspondent for Baird-friendly paper The Era:

‘Hers is so creditable a performance that she deserves to recline (in stone of course) on the pediment of the palace of television which will be built one day in England.’

After which, once the curtains had come together, the Coliseum’s innovative revolving stage moved the caravan on and brought the next act into the light.

Later in the day, the Lord Mayor of London and Oswald Moseley, MP, were televised from the Baird offices to the Coliseum, and over the next fortnight they were followed by numerous public figures of the day, including MPs Ellen Wilkinson, George Lansbury and Minister for Transport Herbert Morrison, as well as Lord Baden-Powell and tennis champion ‘Bunny’ Austin.

Not that the show was all politics and prophecies. During each presentation requests from the stage audience were phoned back to the studio, as one report noted:

Do you mind putting out your tongue?” was asked of Moseley on the first afternoon. ‘“Certainly not,”’ was his reported response. ‘’I think the speaker must be a doctor,” said the spokesman, and out came Mr Moseley’s tongue. The audience could see him laughing.

As this first turn came to a close, Baird’s photograph was displayed on screen, apparently prompting a roar of approval from the packed audience.

In later shows, artists on the same bill as Television went across to Long Acre to sit before the transmitter. American sopranos Helen Yorke and Virginia Johnson imaginatively performed a duet with Helen on stage and her partner on screen. Ray Herbert recalled that comedian George Robey took this intermedial performance style a step further:

He commenced his act in the normal way, but after a short time the television screen lit up displaying Robey as a bride in a talking film [presumably the one Baird had used to demonstrate his ‘tele-talkie’ system]. Leaving the film to entertain the audience he look a taxi to the studio and concluded his turn from there.

Both of the trade magazines for the acting profession, The Era and The Stage, ran detailed reviews of each of the variety bills at the main London houses, and in Television’s second week, both columnists accepted without question the system as a turn, much like British Movietone newsreels, that deserved its place on the bill. Probably only the technical complexity of putting on this show, together with the associated costs, prevented other halls from replicating the idea.

Across the fortnight, press responses to the show were mixed, and can be fairly represented by the judgement of the London correspondent of The Yorkshire Post:

As an entertainment television is at present barely on a technical level even with the earliest moving pictures. But to be able to transmit even these rough images on a scale that makes them visible to a large audience is a definite achievement which may in future years be regarded as a landmark in television development.

The Baird company benefitted from both extensive coverage and the £1,500 profit netted from the booking. Leaving the Coliseum, the system went on a European tour, first to Berlin, where a promising co-venture was developing, then Paris and finally Stockholm.

Yet this form of large-screen technology, with its more than two thousand bulbs, had no future, being as one commentator has described it, ‘a “brute-force”, inelegant, single channel, mechanical system suited only for low-definition television reception.’ Baird and his collaborators dropped development of it after the end of the year.

[OTD post no. 227; part of a long-running series leading up to the publication on 8 January 2026 of my book Magic Rays of Light: The Early Years of Television in Britain, which can now be pre-ordered from Bloomsbury here.]

Leave a Reply