OTD in early British television: 12 August 1939

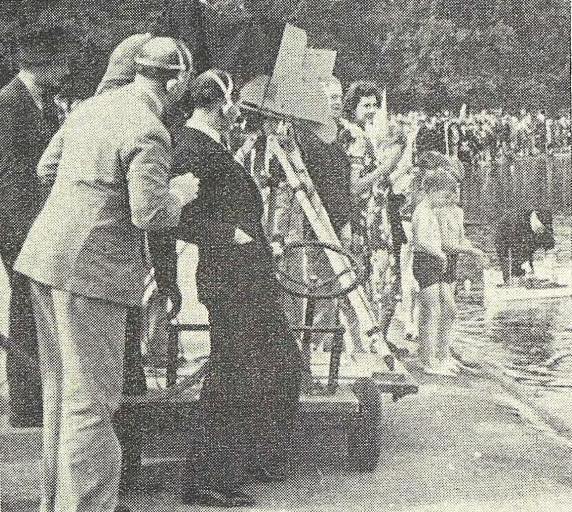

John Wyver writes: The afternoon of Saturday 12 August 1939, three weeks before the declaration of war, saw one of the BBC’s mobile control units in Kensington Gardens for a leisurely hour-long outside broadcast from the edges of the Round Pond. Four commentators – Elizabeth Cowell, Edward Halliday, J.C. Smith and H.B. Tucker – were on hand to talk to model aeroplane and boat enthusiasts, as well as those fishing for tiddlers.

The broadcast prompted one of Grace Wyndham Goldie’s finest Listener columns, which I reproduce here in full:

Last Saturday, we had a highly amusing programme about Kensington Gardens. It was one of those valuable experiments in actuality, Television Surveys. lt began with a ‘close shot ‘ of Mr Halliday who was telling Miss Cowell about Kensington Palace. The gardens, he said, were permeated (for him) with the spirit of Queen Victoria; the southern Wren front was better architecturally than the eastern Kent front; and so on. Miss Cowell appeared enthralled. And then, taking his arm, began to stroll forwards.

Immediately it was clear that these activities had collected vast crowds of people. In the distance park-keepers could be seen marshalling and controlling them. But there were curious little oases which were uncontrolled and unmarshalled. Here was a nurse-maid with a prettily-dressed child: over there two small boys were sitting on the grass and fingering a toy yacht: in the middle distance was a collection of perambulators.

What could this mean? It was soon clear. For the stroll of the commentators took them towards the nurse-maid and we were in the middle of the First Interview. The Second Interview was with the boys of the yacht, and we were beginning to move over to the perambulators when, suddenly, a little half-naked figure thrust itself into the foreground of the picture.

It was a typical London urchin of the parks: his bathing drawers were held up precariously by one hand: he was shrill, talkative, inquisitive and totally unselfconscious. He got in the way. He shouted: ‘I’ve got one like that at home’. He screamed: ‘Oo ! Miss, look over there!’ He was joined by a friend who was equally unselfconscious and whose bathing drawers were even more precarious. And from the moment they appeared the programme, which until then had been as dead as mutton, sprang into life.

Things were bound to get better, I admit, even without the help of this pair for as soon as we could watch model aeroplanes flying and model boats sailing on the Round Pond there were a hundred things to grip our attention. But it is worth while stressing the immediately enlivening effect of the urchins on the programme all the same.

Because here, in miniature, is one of the great, pressing, and important problems which faces every producer of an actuality programme. He wants to concentrate into a limited time the typical flavour of a place. And behold! as soon as the television vans arrive the place is no longer typical, since crowds collect and have to be controlled, otherwise the programme is impossible. That is problem one.

Then he cannot, any more than a film producer can, leave people and incidents entirely to chance; for they may chance to be both dull and untypical. He must, then, select. But he cannot do what the film producer does – make his selection in the cutting room after the pictures are taken. So he must make his selection beforehand and ‘plant’ suitable people for us to meet.

That is problem two, and the result may easily be what it was at the beginning of Saturday’s programme, highly embarrassing, since the unfortunate commentators have to maintain an elaborate pretence that all these encounters are accidental when we viewers can very well see that they are nothing of the kind.

What, then, is he to do? There are, I suggest, only two ways out of the dilemma. One, the most difficult, is to use more art in concealing the selection. The second, and I believe much the more acceptable, would be to drop the pretence.

Commentators could tell viewers at the beginning of the programme, for example, that various people who were met in the morning in the gardens had been asked to be present in the afternoon but that it was hoped that other people of interest would appear on their own.

The distinction in any case will be obvious to viewers. And if it is admitted, they will not feel that they are being deceived. That, surely, is of the utmost importance. For the strength of Television actuality is that it does make us feel that we are seeing for ourselves, and that the thing we are seeing is not faked. And once this tremendous asset is thrown away a television version of real life tends to look only more clumsy than the ‘real life’ of the films.

[OTD post no. 238; part of a long-running series leading up to the publication on 8 January 2026 of my book Magic Rays of Light: The Early Years of Television in Britain, which can now be pre-ordered from Bloomsbury here.]

Leave a Reply