OTD in early British television: 12 May 1937

John Wyver writes: Today’s post is an extract from chapter 7 of Magic Rays of Light: The Early Years of Television in Britain, to be published in January 2026.

On or about 12 May 1937 British television changed. That was certainly the view of those producing the service from AP, and the assessment was shared by many of the estimated 60,000 who, from Ipswich to Brighton, were watching.

From 15.04 to 15.59 on that Wednesday afternoon a live outside broadcast from Hyde Park Corner featured scenes of the waiting crowds and then of the passing Coronation procession on its return journey to Buckingham Palace.

Although it does not enjoy the centrality in popular memory of Elizabeth II’s Coronation 16 years later, the pomp and ceremony that marked George VI’s accession was profoundly significant at the time. And the new medium made its modest contribution as, for the first time (leaving aside earlier test transmissions), viewers could see live pictures from a remote location of a defining occasion of international significance.

For one commentator this was ‘an event that marks an epoch’, while for Television magazine, it was ’impossible to over-emphasise the importance of the successful transmission of the Coronation procession.’ ‘Undoubtedly,’ the journal’s editorial asserted, ‘it marks the commencement of a new era in television and indicates its true sphere of usefulness.’

Six months earlier, at the moment of the launch of Alexandra Palace, the TAC was preoccupied with a deluge of technical matters, contracts and patents, but it paid special attention to two significant broadcasts: the opening day, inevitably, and the Coronation.

At a meeting in mid-December Noel Ashbridge reported that it was doubtful whether permission could be secured for television broadcasting from inside Westminster Abbey. Instead, he proposed, ‘it might be necessary to obtain a “close-up” of the procession for television purposes at some point away from the Abbey.’ Although it was not an argument that would be won in 1937, Lord Selsdon responded that he felt strongly that if cinema newsreels had access to the Abbey then this facility should also be extended to television.

Combining the relatively light infrastructure required for live radio outside broadcasts with the complexities of a studio set-up, a first mobile television unit was commissioned from Marconi-EMI with the Coronation as an immovable deadline. Three substantial vehicles, dressed in distinctive dark green livery, were delivered at the end of April, leaving only ten days for testing.

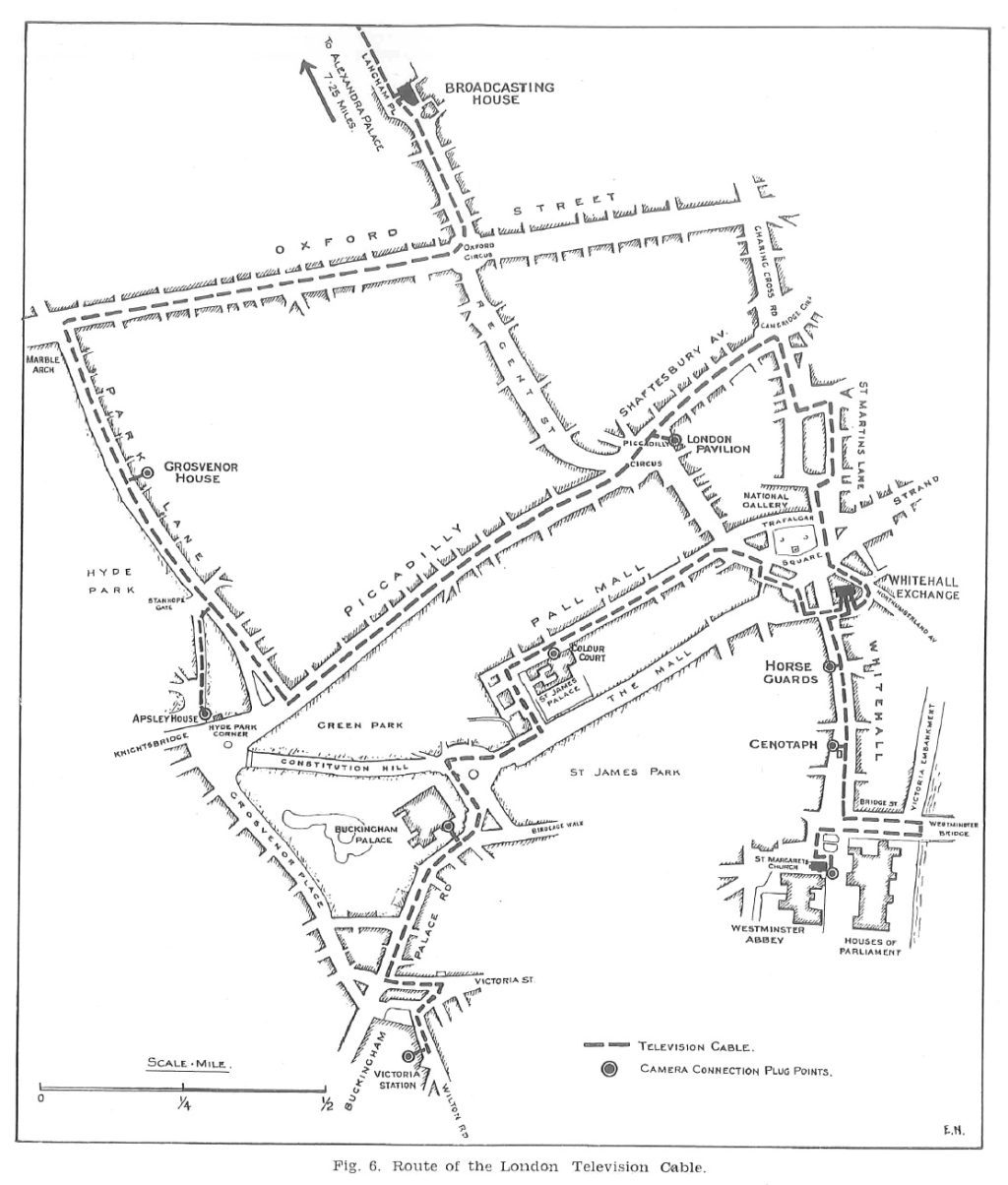

Since standard telephone cables used for OB audio were, apart from across short distances, unsuitable for vision transmission, the key challenge of relaying images back to Alexandra Palace for onward broadcast was met in two ways. An initial solution was the installation in 1935 in existing underground ducts of a ‘balanced-pair’ low-capacitance copper cable of a kind designed in the EMI laboratories, in conjunction with Siemens.

Laid by the Post Office, this linked central London locations with Broadcasting House, with an extension running to AP. The eight-mile circuit eventually ran from BH under Oxford Street to Marble Arch, and then down Park Lane to Hyde Park Corner and the Apsley Gate site from which the images of the Coronation procession were sent.

From there it ran along Piccadilly and up Shaftesbury Avenue to Cambridge Circus, and then down St Martin’s Lane to the Whitehall exchange just south of Trafalgar Square. Here it split, with one line running along Pall Mall and on to Victoria Station, and the other going under Whitehall, past the Cenotaph and ending at Westminster Abbey. It was envisaged that a third link would take the cable through the City but this was never laid.

In the six months before Coronation Day, the schedules were dotted with numerous elements related to the event, including in November a presentation of a 15-foot long Model of the Coronation Procession with 3,000 figures. Visitors from across the Empire arriving for the ceremony were featured on Picture Page.

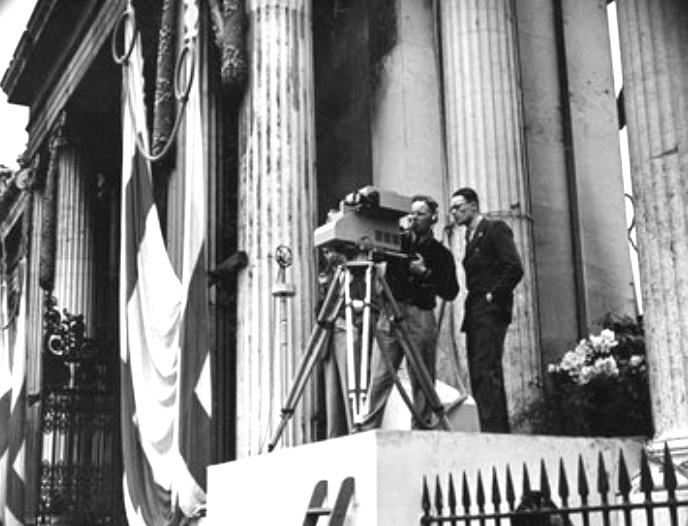

Two days before the main event the first test shots were transmitted from Apsley Gate. This ornate triple-arched structure designed in the 1820s was chosen not only because there were elevated positions as well as a place for a camera on the pavement, but also because the afternoon sun could be behind the cameras, and so that the MCR and stand-by transmitter van could be safely parked close by.

On the morning itself conditions were overcast and there was a blustery rainstorm at lunchtime. Just after three, as John Swift recalled, ‘the screens flickered into life to show the dim, wraithlike figure of a despondent [Freddie] Grisewood [the designated commentator]. He said that conditions were not good, that it was terribly bad luck and all that, and that everybody on location was dreadfully upset.’

In fact, the images were acceptable, although the dim light meant that the telephoto lenses could not be deployed. One camera set on a plinth picked up the marching soldiers and the coaches as they came down East Carriage Drive, and another saw them pass away in the direction of Constitution Hill. The pavement camera panned quickly with each vehicle passing before re-setting to catch the next.

Watching the procession, L. Marsland Gander reported that, ’Such details as the emu’s feathers in the Australians’ slouch hats, and the plumes in the Guards’ bearskins showed plainly on screen.’ He glimpsed the Duchess of Kent, and saw Queen Mary quite distinctly. ‘Then for just brief moment,’ he wrote, ‘I saw the King, wearing his crown, as the coach passed through Apsley Gate.’

Manufacturers and retailers had set up numerous temporary exhibition spaces, Sets were loaned to hospitals, and at Ranelagh polo ground one was installed in a marquee. At the Odeon Cinema, Southgate, a hundred people apparently watched on a single receiver and at the end of the broadcast they ‘stood up and cheered wildly.’ The GPO installed six receivers in Memorial Hall near the company’s headquarters in St. Martin’s le Grand, and there entertained some 800 distinguished visitors.

Today, two fragmentary moving image records offer traces of what the experience was like for those watching. Recognising the significance of the transmission, the Television Service made a 6-minute commemorative film which captured the installation of the television cameras, the crowds on the day, the marching bands and a fleeting glimpse of the monarchs’ coach passing rapidly by.

More remarkable still, and yet frustratingly unclear, are 24 seconds of 16mm footage, comprising six shots, filmed by an employee of the Marconi Company, J.E. Davies, of his television screen showing the procession. Flickering, unfocussed and indistinct, the sequence nonetheless features the royal coach passing by, and just like Marsland Gander nearly 90 years ago it is possible to glimpse the king wearing his crown.

Both of these are featured on the BBC History page, ‘Two Coronations’.

In one of the many press round-ups, Gerald Cock celebrated the distinctiveness of his medium: ‘In my opinion, much of the fascination of television, and to a great extent its future, is bound up with actuality, a virtue which it alone possesses, and which the news reel, with its time-lag, misses.’

And the critic K.P. Hunt concurred, writing that ‘despite the obvious fact that the film was bound to be superior in technique, there was in the latter that lack of actuality which even with its shortcomings only television can give. There is that psychological difference in the knowledge that what is being seen is taking place at the very instant. The possibilities which the success opens up are illimitable.’

‘It is impossible,’ Hunt added, ‘to over-emphasise the importance of the successful transmission of the Coronation procession.’

A personal note: today is my birthday, and while I very much wanted to post this today, I am taking the rest of the week off. Reprises of some of my favourite recent posts will appear here until Saturday, after which normal service will be resumed.

Leave a Reply