OTD in early British television: 18 December 1938

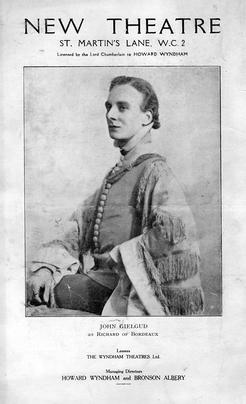

John Wyver writes: There was a sense of increasing confidence at Alexandra Palace at the end of 1938, with sales of receivers finally picking up and programmes becoming both more ambitious and more polished. This was reflected in announcements for a clutch of major drama productions over the Christmas period, including Noel Coward’s Hay Fever on Christmas night, an Edgar Wallace thriller, The Ringer, a re-run of Once in a Lifetime, and on the evening of Sunday 18 December, Gordon Daviot’s Richard of Bordeaux. (The image is a souvenir made by Motley of the original stage production in 1933, from the collection of the V&A; for more see below.)

A historical romance about the relationship of Richard II and his first wife, Queen Anne of Bohemia, this play had been a huge hit in the West End in 1933, and subsequently on tour. Gordon Daviot was a pseudonym for the author Elizabeth MacKintosh, who also wrote under the name of Josephine Tey. Directed by and starring John Gielgud, the production at the New Theatre is credited with transforming the actor into a major star.

In 2003 Samantha Ellis for the Guardian looked back at the critical reception:

Punch‘s critic praised the “startling vividness” of the writing, which gave “the illusion of taking a peep into a past which is made to come alive”. Theatre World‘s critic was impressed that the “characters speak and behave neither like fustian puppets nor bright young imbeciles, but like real flesh-and-blood creations”. In the Daily Telegraph, Sydney W Carroll recorded his “satisfaction that a woman dramatist can exhibit such a masterly insight into male characterisation” and critic after critic praised her use of contemporary dialogue.

Not everyone was convinced by Gwen Ffrangcon-Davies, playing Richard II’s hapless queen. The New Statesman‘s critic felt she was a victim of bad writing – “what an empty little part it is!” – and the Sketch‘s otherwise ecstatic reviewer found her performance to be “somewhat etherealised”.

But the critics were unanimous in falling for Gielgud. He had had good reviews before, but none like these. The New Statesman praised his “attractive and arresting acting”, his “morbid, feline elegance”. Taking his cue from the “ecstatic roars” of the audience, the Daily Express crowned Gielgud “the supreme idol of the pit and the gallery, where most of the intelligent playgoers sit”.

Approaching the television production, tyro drama producer Michael Barry went to meet Gielgud to persuade him to reprise his performance. Preoccupied with the stage at this point, Gielgud was also irritated by a dispute with the BBC over a radio contract, and he declined. ‘I came from the meeting,’ Barry recalled in his delightful memoir From the Palace to the Grove, ‘with the impression of a finely strung violin vibrating.’

Barry was nonetheless pleased that Gwen Ffrangcon-Davies once again took the role of Anne – ‘exquisite’, he hymned – and Andrew Osborn, later the producer of the BBC’s original Maigret series, stepped up to play the title role. John le Mesurier took on the small part of Sir John Montague. The producer was also acute in his analysis of the play, which he described as

written in a scenario form that was much more amenable to the needs of television than most well-made stage plays. The narrative moved forward in continuous sequences of strongly written, short scenes, and I enjoyed working on it.

Writing in The Listener, Grace Wyndham Goldie could hardly contain her enthusiasm:

There were dozens of scenes, scores of fourteenth-century costumes. an enormous cast, Miss Ffrangcon Davies repeating her charming performance as Anne of Bohemia and Mr. Andrew Osborn being most sensitive, finished and moving as Richard. The whole thing was a delight to the eye and a first-rate entertainment. And all this in one’s own sitting-room by turning a switch.

Just think of it. The real thing. For television plays, in spite of their increasingly film-like handling, do succeed in remaining different in quality from film. They must inevitably be different. Even Richard of Bordeaux — though this was extremely film-like in its detail. But in spite of that this was a peak production; the most complicated and complete I have yet seen. And the latest I have seen. This is constantly happening. The latest is the best. In other words, television plays are getting better and better every minute. (29 December 1938)

We’ll return in a future post to what the critic might have meant by ‘film-like handling’, and why she thought this a concern. But when the AP executives opened their end-of-year copy of the weekly, they must have felt that their growing confidence was, in some measure at least, absolutely justified.

Image: This rather fascinating object from the collection of the V&A is a souvenir in the form of a large toy theatre cut-out of Gwen Ffrangcon-Davies as Anne, which was originally paired with one of Gielgud as Richard. The V&A website also notes that

Inscribed on the back of this figure are the names Elizabeth Montgomery (Wilmot), Sophia Harris (known as Sophie) and M. F.. Harris, (Margaret ‘Percy’ Harris) who were sisters. In the early 1930s the three girls formed the theatre design partnership The Motley Theatre Design Group.

Or, simply, Motley. Their designs for Richard of Bordeaux on stage were highly praised, and allowed the young women to launch a successful business that lasted for more than two decades, and included a number of triumphs for the Shakespeare Memorial Theatre in Stratford-upon-Avon. Glen Byam Shaw’s 1955 production of The Merry Wives of Windsor, for which Motley designed sets and costumes, was the first production from Stratford to be televised (in part) via a live outside broadcast.

I’ve found another response to the production which is an interesting complement to GWG’s review. For The Observer, ‘E.H.R.’ wrote that the drama was

‘remarkable for that special quality which belongs to television, and which is not found either in stage or in cinema work. The quality is hard to define, but is due in part to dramatic continuity not interrupted by the falling of curtains and also possibly to a sense of both reality and intimacy. However this special quality arrives it is both good and pleasing.’