OTD in early British television: 19 July 1939

John Wyver writes: More or less from the start of the Alexandra Palace operation viewers wanted director of television Gerald Cock to schedule a regular slot for youngsters. Cock pleaded shortage of resources and airtime, but eventually offered up a first clutch of programmes on the afternoon of Wednesday 19 July 1939.

The Daily Telegraph‘s correspondent the next day declared it ‘an hilarious success’.

Twenty children of BBC employees formed an audience in the studio. and also unknowingly provided part of the entertainment. A camera concealed from them showed pictures of the youngsters, from time to time, intent on the stage and rocking with laughter.

Delightfully, Grace Wyndham Goldie’s verdict was considerably more circumspect:

Television doesn’t yet provide a Children’s Hour. But there crept into last week’s programmes the first of a series which is coyly described as being ‘for the younger viewer’. Now this is important. For the Children’s Hour is one of the triumphant successes of sound broadcasting and the first steps towards a television Children’s Hour are worth watching.

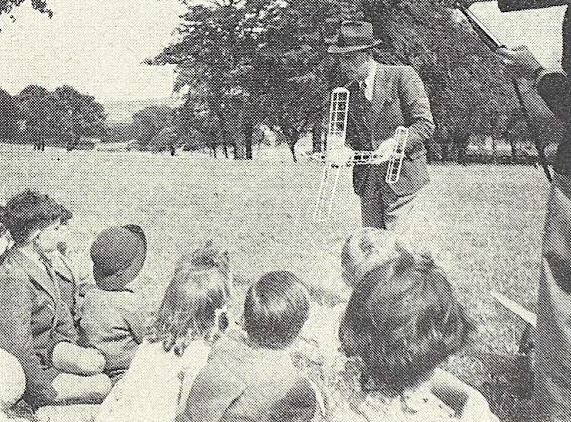

lt began well out of doors with a riding display and a demonstration of model air-craft (above). lt went on well with a Disney Cartoon and a Punch and Judy show. And then came the collapse. There was an ‘Intimate Cabaret’ done before an audience of twenty or thirty children. This audience was, to my mind, a mistake. Television, because it must let us see, cannot make that appeal to the imagination of the individual child which is one of the trump cards of the Children’s Hour from Broadcasting House.

What can it do instead? It can play its own trump card, that direct contact between the performer and the viewer which is peculiarly valuable when the viewers are children whose attention needs to be gripped. And this tremendous asset was thrown away by letting the performers do their turns to an audience in the studio while we, the viewers for whom it was all intended, merely looked on.

And the audience was not even allowed to remain an audience. lt strayed on to the stage; there were competitions; things got more and more out of hand. By the end we had a kind of miniature school treat. Embarrassed children were given pieces of melon to eat and babies’ bottles to suck and were bombarded with awkward questions as to whether they were enjoying themselves.

The position of the comedians was even more embarrassing than that of the children. I am a great admirer of Mr. Leonard Henry and I felt for him. Having a song about Income Tax and Mothers-in-law, he was forced to point out to the uncomprehending children the places where laughter and applause were expected.

Do I seem to be stressing all this? It is, I think, worth stressing. Partly because of its tone, which needs attention. Partly because it was a fine example of that odd attitude of mind which confuses the intimate with the unrehearsed. Intimacy, as we all know, is one of television’s strongest points. We always welcome it. But watching unrehearsed and unpractised people behaving informally is not necessarily the same thing as being intimate. And it may or may not be entertaining. lt is, alas, usually not.

[OTD post no. 214; part of a long-running series leading up to the publication of my book Magic Rays of Light: The Early Years of Television in Britain in January 2026.]

Leave a Reply