OTD in early British television: 25 March 1938

John Wyver writes: On the afternoon of Friday 25 March 1938, The Mercury Ballet, by this point also known as Ballet Rambert, gave the second screen performance of the 19-minute Bar Aux Folies-Bergère, choreographed by Ninette de Valois to music by Romantic composer and pianist Emmanuel Chabrier, selected and arranged by Constant Lambert.

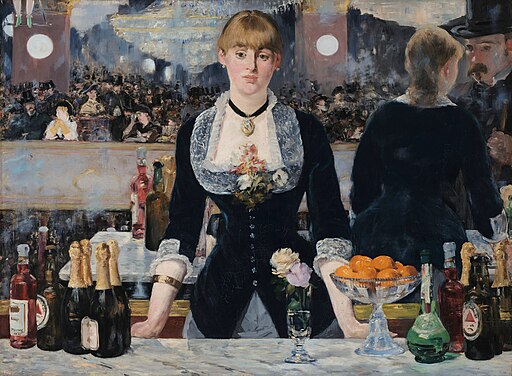

Elizabeth Schooling danced the role of ‘La Fille au Bar’, and others in the cast Celia Franks, Prudence Hyman and Walter Gore. William Chappell created the costumes and setting, which had been made for the tiny stage of the Mercury Theatre and imported into the studio, and which as can be seen from a production photograph aimed to replicate the details of Édouard Manet‘s great and enigmatic 1882 painting Un bar aux Folies Bergère.

As Wikipedia tells us of the work on stage, which was the only piece created by de Valois for the company:

In 1934, it was noticed that Elizabeth Schooling had a very similar appearance to the barmaid in Édouard Manet’s painting Un bar aux Folies Bergère. Marie Rambert’s husband Ashley Dukes suggested there might be a ballet around the picture, also introducing can-can dancers. Bar aux Folies-Bergère was first performed on 15 May 1934 at the Mercury Theatre, Notting Hill, London. Although the role was created by Pearl Argyle, Schooling danced it subsequently….

The curtain opens on the barmaid looking into space then busying herself wiping off bottles and glasses. Adolphe and Gustave enter and orders drinks. A waiter, Valentin, is in love with the barmaid, whom he persuades to come from behind the counter to dance with him. When the can-can dancers appear (entering through the audience, as at the real Folies Bergère) and dance, she retreats behind the bar again. When La Goulue does her turn, Valentin becomes besotted with her, breaking the heart of the barmaid, who, after everyone has left and the cleaner starts her work, finally resumes the pose of Manet’s painting.

Writing in The Listener, ‘G.G.W.’ judged the screen version harshly because with a cast of 14 it ‘failed to take into account the limitations of the small receiver screen.’ Nonetheless the critic enthused about the opening, which began with a shot of Manet’s famous painting on the backcloth and then slowly superimposed on this a dancer

so effectively that it was only just before she began to move that we realised that the change had taken place. This was particularly commendable because it was an example of television doing what only television can.

But from this beginning we went on… for some twenty-five minutes during the greater part of wh1ch time so much was happening at once that the viewer could not see the wood for the trees. This is no reflection whatever upon the quality of Ninette de Valois’ ballet as ballet. Those who have seen it in the flesh at the Mercury Theatre will not need telling how good it is.

And no doubt it was equally enjoyable for those who watched it in the flesh in the studio at Alexandra Palace. But if the producer, as he should, was rehearsing by looking into a receiver instead of watching actually in the studio he will know what a very different thing such a production can be when it is reduced to the scale of the television screen.

What, then, is to be done about it? Obviously ballet is not to be barred from the programmes. Indeed it should be capable of producing some of the very best of them. Neither is the cast of the production to be limited to two or three dancers, but it does seem that though where dancers are few the background may be complicated if the producer so desires, where the dancers arc anything over five or six in number, they must perform against an entirely plain background if we are to be able to see them at all.

Interesting critique of what sounds like an over-ingenious production. And you can see the Mercury Theatre of this period recreated in Vicky’s early audition for Lermontov in The Red Shoes. But not sure I’d call Chabrier ‘romantic’, though he’s definitely Belle Epoque.

Excellent reference, Ian – thanks. As to Chabrier, might I offer this?

https://theromanticmovement.com/emmanuel-chabrier/