OTD in early British television: 26 January 1926

John Wyver writes: This, my friends, is The Big One. Ninety-nine years ago, on the evening of Tuesday 26 January 1926, in rooms above what is now Bar Italia in London’s Soho, John Logie Baird gave the first public presentation of what he called ‘true television’.

Invited guests, along them members of the Royal Institution and their partners, some in full evening dress, climbed the three flights of narrow stone stairs at 22 Frith Street. After waiting in a draughty corridor, they were ushered six at a time into the maverick inventor’s tiny rooms.

Among the witnesses was a Times correspondent, whose three-paragraph story two days later was relegated to two-thirds of the way down a page nine column:

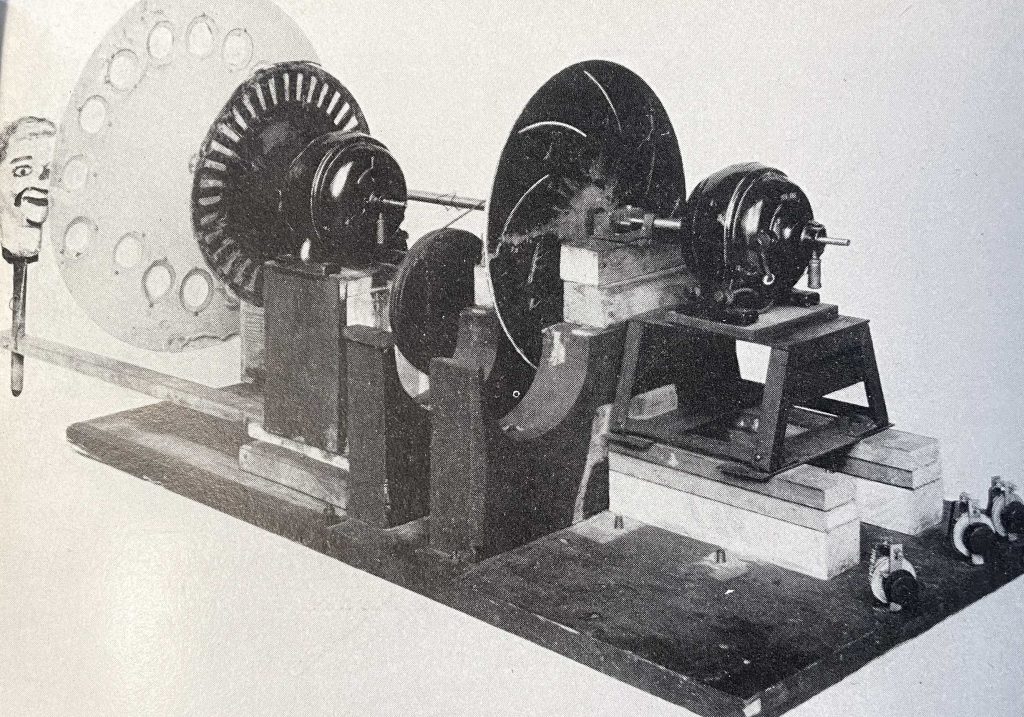

Visitors were shown a transmitting machine consisting of a large wooden revolving disc containing lenses, behind which was a revolving shutter and a light sensitive cell.

Rather more colourfully, Baird recalled that the disc was ‘a most dangerous device, had they known it, liable to burst any minute and hop round the room with showers of broken glass.’ After a sketchy explanation of the workings, The Times’ prosaic first draft of history continued:

First on a receiver in the same room as the transmitter and then on a portable receiver in another room, the visitors were shown recognizable reception of the movements of the dummy head [the puppet “Stooky Bill”] and of a person speaking.

What was already called, on the model of “listening-in” to the wireless, “looking-in” involved peering down a cardboard funnel, at the end of which could be seen, as another journalist detailed,

features [that] came out as rather blurred black lines in an orange light… the change of expression from opening the mouth to smiling and putting out the tongue could be seen.

A hand, a pipe and a notebook being flicked through were similarly recognisable. The images just about fulfilled Baird’s definition of “true television”, being

transmission of an object with all gradations of light, shade and detail so that it is seen on the receiving screen as it appears to the eye of an actual observer.

Baird’s apparatus is precisely described in Antony Kamm and Malcolm Baird’s John Logie Baird: A Life, their excellent biography of the latter author’s father:

[It] incorporated, at the transmitting end, a lensed disc, made of a double layer of cardboard, about two feet in diameter with a double spiral of two sets of eight lenses, revolving three hundred times a minute. The lenses, each about three inches in diameter and secured by three screws, were the same as those used in bicycle lamps. Left to itself, this device divided the image into eight strips.

The final picture of thirty-two [vertical] lines was obtained by passing the light impulses from the transmitting disc through a slotted disc, and then through a further disc, containing a single spiral slot, rotating once every four revolutions of the lensed disc. This multiplied the number of strips by four.

The picture received, via a single disc spiral of 32 holes for display on a ground glass screen, was six and a third centimetres wide by eight and a quarter inches tall. As the inventor later noted, somewhat hopefully, of those who were there on this singular occasion,

The audience were for the most part men of vision and realised in these tiny, flickering images they were witnessing the birth of a great industry.

Image: John Logie Baird’s original mechanical television apparatus, with Stooky Bill just visible on the left, later donated to the Science Museum, London; reproduced from John Swift’s 1950 book Adventure in Vision.

Leave a Reply