OTD in early British television: 6 July 1937

John Wyver writes: ‘Fashion’ in programmes from pre-war Alexandra Palace invariably meant clothes for women, but there was an outlier on the evening of Tuesday 6 July 1937. Men’s Dress Reform was a 17-minute programme produced by Mary Adams looking at costumes entered for the Coronation competition held under the auspices of the Men’s Dress Reform Party. It is fair to say that it was not a success.

Host Dr J.C. Flugel, author of The Psychology of Clothes, explained that the Men’s Dress Reform Party [MDRP] aimed to promote clothes which were healthy, attractive and practical. The competition was divided into two classes: (a) office, professional or other vocational wear, and (b) ceremonial or evening wear.

As an anonymous television reviewer commented drily in The Listener:

No first prize was awarded because the judges felt that no design reached the required standard…

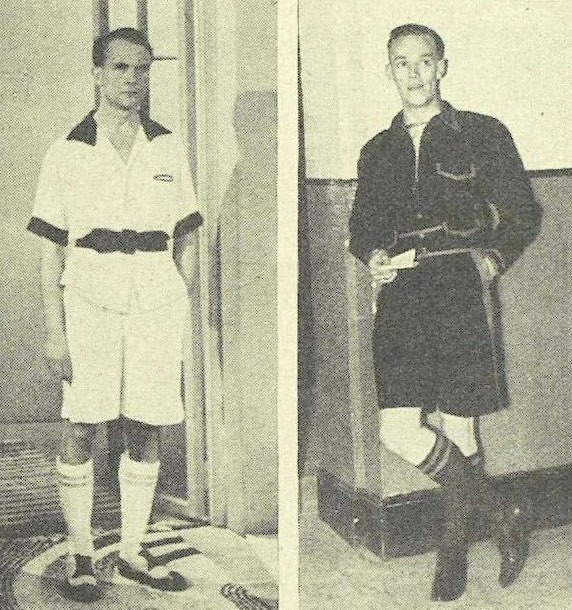

Part of the interest of the costumes no doubt lay in their novel colours, for which we could only take the word of Dr. FIugel and the other commentators, though we were able to judge their curious shapes for ourselves.

This is of course an inevitable limitation of television, but it was fully made up for by the convenience of being able to express our feelings regarding the costumes shown without risk of offending their designers, who were safely at Alexandra Palace several miles away.

The judges themselves admitted that the designs were disappointing. As Mr. Bridgland said, they were not beautiful nor were they practical… Curious stress seems to be laid, by so many reformers of men’s dress, on the value of shorts.

However, even though the designs shown at Alexandra Palace last Tuesday are not likely to have a very profound influence on sartorial taste during the next ten years, they nevertheless provided viewers with an entertaining ten minutes, and plenty of laughter.

Amusing as this clearly was, the MDRP attracted significant attention in the interwar years, and there are a couple of fascinating articles (both pay-walled) about its influence, ‘Better and Brighter Clothes: The Men’s Dress Reform Party, 1929-1940’ by Barbara Burman, and ‘The great male renunciation: men’s dress reform in interwar Britain’ by Joanna Bourke, both in the Journal of Design History, in 1995 and 1996 respectively.

Joanna Bourke writes:

Modernity was a mixed blessing. In 1929, the Men’s Dress Reform Party was established in response to what its founders regarded as the heinous modern age. One of them, John Carl Flugel (a psychologist from University College London), contended that since the end of the eighteenth century men had been progressively ignoring brighter, more elaborate, and more varied forms of masculine ornamentation by ‘making their own tailoring the more austere and ascetic of the arts’.

He called this event ‘The Great Masculine Renunciation’, or the occasion when men ‘abandoned their claim to be considered beautiful’ and ‘henceforth aimed at being only useful’. In the face of inter-war feminism and the denigration of masculinity, the professionals who joined the Men’s Dress Reform Party regarded it as their duty to lobby for the aesthetic liberation of men…

The experience of warfare between 1914 and 1918 was crucial in focusing attention on the bodies of men. Dress reform was necessary not only for the sake of enhancing masculine beauty, but also to prevent the further degeneration of the ‘British race’.

Health and hygiene were high on the agenda of male dress reformers. Although they failed to achieve their more grandiose hopes, they were representative of a broader movement towards freeing men from constraints imposed by the state, employers, and the tailoring trade.

There is also a fascinating (and accessible) 2016 article for The New Inquiry by Autumn Whitefield-Madrano, ‘Men’s fashion, eugenics and cultural capital’:

What’s interesting about the MDRP is its split between a vision that even today seems progressive (a lessened emphasis on traditional masculinity) and a cause that seems abhorrent. Part of the MDRP’s cause revolved around eugenics: If the ‘right’ men were to showcase their appearance, they would be more attractive to the ‘right’ women, and more ‘right’ babies (that is, white babies born into the professional class) would be created…

Eugenics is tied to class, not just race, and the MDRP has an interesting fabric here too. The party claimed to be for people of all classes, but the fact was that most of its members were middle- and upper-class, and that they weren’t advocating for more accessible clothes, but more fashionable ones…

The suit that the MDRP was fighting against was the very thing their grandfathers had fought for: a uniform of sorts that would theoretically allow for meritocracy to flourish, since it was more difficult to display wealth through the suit as opposed to the ruffles of the aristocracy. The ruffles were seen as oppressive; eventually, the suit that replaced it became seen as the same.

Image from The Listener showing (left) one of the runner-up designs, and (right) a design for a telegraph boy’s suit.

[OTD post no. 201; part of a long-running series leading up to the publication of my book Magic Rays of Light: The Early Years of Television in Britain in January 2026.]

Leave a Reply