OTD in early British television: 6 September 1933

John Wyver writes: Wednesday 6 September 1933 saw the second performance on the 30-line service of Rokoko, a musical comedy programme selected from operettas by Leo Fall, Millocker and Emmerich Kalman. Henrik Ege contributed original dialogue and there were additional numbers by Mark Lubbock. Rokoko had been first played in late July, and it was one of the clearest examples so far of producer Eugene Robb’s ambition for the very basic portrait-format images of which the technology was so far capable.

Of the first broadcast, ‘Spectator’ wrote in Television:

Having secured the engagement of Naima Wifstrand, Sweden’s premier musical comedy actress, the producer determined to present her in an appropriate setting. So they all set to work, costumiers, carpenters, musical arrangers and dialogue writers and Rokoko, billed as the first television musical comedy programme, was the result. If the story was not altogether new, it was piquant, and the presentation was fresh and ingenious in detail.

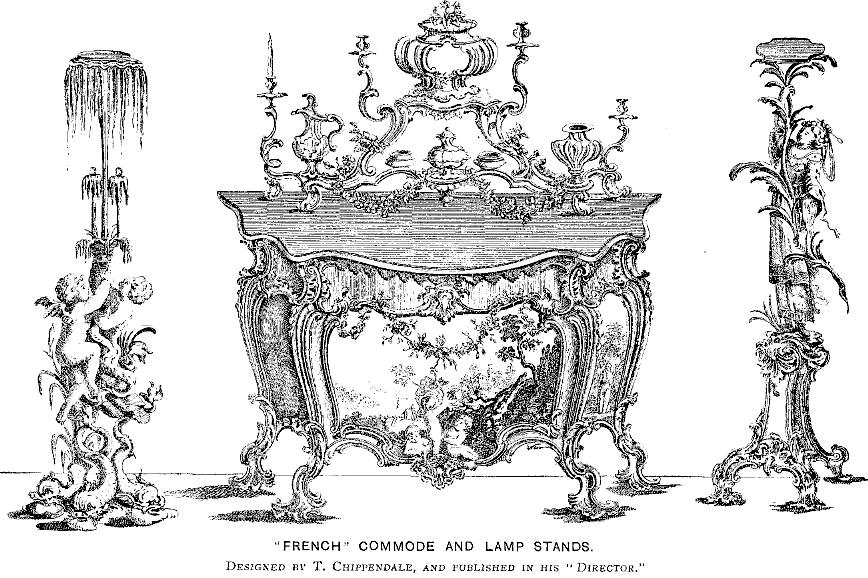

The show opened with drawings depicting rococo design in its various forms, and the fussy elaboration of the costumes, the twists and curves of the figures and the furniture, emphasised in black and white, carried the looker straight back to the eighteenth century.

This is where television scores; dialogue lasting a quarter of an hour would scarcely take a listener in spirit to the same point, but add a picture and the years dissolve in a moment. In this way action is speeded up, and with the aid of a “Televisor” a theme may be developed in half an hour that a producer could not otherwise attempt to present to the microphone in less than sixty minutes.

George Mozart played Bobo, the comic count chamberlain, in just the right vein, and with a laughable lack of delicacy conveyed the Empress’s wishes to the Prince that he should make love to the new arrival at the court in the interests of another form of alliance which Austria wished at the time to contract with France.

The reluctance of the Prince was painful to behold, and we learned with sadness that his heart was elsewhere engaged, but later when the visitor was seen to be the fair Pompadour, he put his country first and proved a keen and rapid worker. In the end news came that the treaty was signed, but not before we had seen some delightful period dancing, minuets and waltzes by Laurie Devine [link is to an OTD post back in February] and Tom Rees.

Personality as displayed by Naima Wifstrand eludes definition, but it is present in full measure, and there is “throb’ in her lively sensitive voice. A great actress though she certainly is, I thought it unfair to ask her to play and sing three characters in half an hour.

Her costumes, deportment and speech were perfect as the Empress Maria Theresa, Madame du Barry and the Pompadour, but the singing voice was inevitably that of Naima Wifstrand, at its best, I thought, in the waltz song from De Kaisirin which has yet to be produced in this country.

Something tells me that we shall see the staircase again; it took a fortnight to build, stands six feet high and is twelve feet long. An artist making a descent emerges from distant vision to the semi-extended position in which her feet are lost to the picture.

The scanner accentuates the perspective and the effect is impressive. Only palaces and grand houses have such stairs, so we may confidently expect to see more high life, and perhaps it will be used for tap dancing and tumbling acts. Stairways form a favourite setting for spectacular scenes on the stage, and musical comedy actresses are practised in taking graceful steps up and down. It is part of the training.

As a newly-built element of studio furniture, the staircase did indeed become a fixture in broadcasts over subsequent months. ‘Spectator’ continued:

John Hendrick gave a very capable interpretation of Prince August Franz von Baldringen, and it would be captious to complain of the anachronism without which it would have been impossible to assemble such a distinguished company, all in the prime of life.

It is a pretty device to bring inanimate objects to life, as when the Prince produced a locket containing a miniature of Madame du Barry, who thereupon appeared before the screen and sang for us.

The second time around, in September, ‘Spectator’ was watching again, and this time was more concerned with technical improvements in the studio in the six or so weeks between the broadcasts:

Clearer distant and semi-extended pictures [that is, long-shots showing a full figure] have been obtained by using more photo-electric cells, which are suspended above the heads of the artists. In the past the engineers have relied upon banks of cells mounted on mobile and adjustable stands, which, with the microphone support, restrict movement.

The new cells hang overhead from the balcony at about ten feet from the ground and from the end of a pole projecting like the bowsprit of a ship over the centre of the studio. In this position the cells offer no distraction or impediment to the artists. Close-up work is not affected by this new arrangement. I wonder whether lookers [that is, viewers] have had better results with other pictures?

In the receiver at Broadcasting House I saw. the dancers in Rokoko much more clearly than in the earlier performance given before the additional cells were fitted, and I thought that the sound in this transmission was also improved.

A programme usually runs more smoothly on its second broadcast and this fanciful and rather complicated production proved to be no excep-tion. John Hendrik is a fine singer and Naima Wifstrand, who had travelled specially from Sweden for the show, repeated her earlier success.

Image: Rococo design for commode and lamp stands by Thomas Chippendale (1753 – 1754); not used in the broadcast.

[OTD post no. 263; part of a long-running series leading up to the publication on 8 January 2026 of my book Magic Rays of Light: The Early Years of Television in Britain, which can now be pre-ordered from Bloomsbury here.]

Leave a Reply