OTD in early British television: 2 December 1938

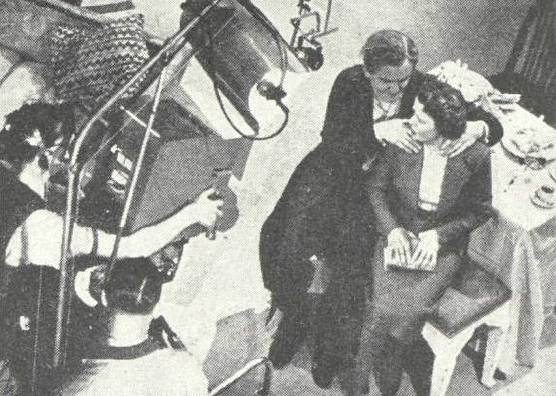

John Wyver writes: ‘First let me say that… Love From a Stranger was, beyond all possible doubt, a winner on the television screen. This play is, as you know, a flesh-creeping affair.’ That’s Grace Wyndham Goldie writing on George More O’Ferrall’s presentation (above) of Frank Vosper’s play adapted from an Agatha Christie short story, first shown on this day, Friday 2 December 1938. The 70-minute drama starring Edna Best and Henry Oscar was played from 9.10pm.

As the service from Alexandra Palace progressed, and as therew was the beginning of pressure to appeal to a broader audience, murder mysteries had multiplied across the schedule. Christie’s one-act play with Hercule Poirot The Wasp’s Nest was given its premiere in June 1937. Scholar of the author’s film and television adaptations Mark Aldridge has characterised it as ‘very well-plotted… but the dialogue and some of the character actions may have struggled to be wholly convincing.’

The writer’s only other pre-war contribution was Vosper’s thriller taken from her ‘Philomel Cottage’. This had been seen on the stage in 1936 and was a successful film in 1937), and now Wyndham Goldie enthused that this version was ‘almost unbearably exciting. The excitement, I grant you, was of a Chamber of Horrors kind. But it was worked up neatly and economically, not by piling on the terrors, but by stressing and emphasising the strong curve of suspense. And it was just this intensity of suspense which made the play so good for television.’ (The Listener, 15 December 1938; also the source of the image.)

‘The acting was masterly,’ Wyndham Goldie felt. ‘Mr. Henry Oscar’s murderer was terrifying because he was credible. And the casting of Miss Edna Best for the victim was a fine stroke. For Miss Best’s gift for being just like everybody’s sister gave the play a reality which doubled its effectiveness. It was as though the centre of all these dreadful doings was that nice little Mrs. Jones up the road.’ Hitchcock aficionados will recall Edna Best as the character Jill Lawrence in the original 1934 film version of his The Man Who Knew Too Much, in which both Frank Vosper and Henry Oscar also appeared.

The television schedules of 1938 and 1939 were packed with crime, murder mysteries and gangster stories, others of which we’ll return to in future OTDs. There was even the Telecrime series that explicitly offered clues for solving a case, and paused the drama while the viewer made up their mind.

Plus ça change, you might think of this plethora. And indeed, on screen at least, murderers are invariably among us. But in my forthcoming Magic Rays of Light: British Television between the Wars I try to develop, drawing on the insights of writers about the literature and theatre of the time, a more nuanced argument about how these plays, which also proliferated on the stage and were echoed by ‘golden age’ crime writing, were in part responses to the trauma of the First World War and the need for reassurance and the reassertion of stability two decades after the dreadful conflict.

Clive Barker has written, in his collection edited with Maggie B. Gale, British Theatre between the Wars 1918-1939, (Cambridge University Press, 2000) of how stage ghosts, horror plays, crime dramas and thrillers of the 1920s and ’30s, all with their ‘illusory portrayals of Death’, became ways for audiences to distance themselves from, and so deal with, ‘the pains of absence created by the mass slaughter of war’. (Barker and Gale’s collection can be ‘borrowed’ virtually here at the wonderful Internet Archive.)

And Alison Light in her brilliant Forever England: Feminity, Literature and Conservatism Between the Wars (London: Routledge, 1991) has suggested that the interwar whodunit, from the pens of Agatha Christie and others, was ‘a literature of convalescence’ which drained away the violence of previous crime fiction, and so became a ‘literature of emotional invalids, shock absorbing and rehabilitating’. Light’s study, which I recommend wholeheartedly, was a key reference throughout the writing of my book.

I’ve been pleased to discover another review of this production, in the Daily Telegraph, 3 December 1938, under the headline ‘Edna Best’s Debut in Television – Horror Play’s Success’:

Edna Best made her television debut last night as the heroine of the horrific

play ‘Love from a Stranger’.· Henry Oscar played the part of the blue-beard

madman. Though some may question the ethics of introducing morbid horror

into the home 1n visual form, none who saw this production can doubt the depth and power of television drama.

The B B.C. had considerably curtailed the last scene. in which Miss Best, conscious of her husband”s murderous intent, tried desperately to stall while the clock ticks on to the appointed hour for the cr1me.

Nevertheless, the producer, Mr G. Moore [sic] O’.Ferrall, built up a tension that

became almost unbearable, and his product1on must be regarded as one of

television’s most notable successes to date.’