‘Radio Times’ welcomes television

John Wyver writes: The Future States conference, about which I have been writing and which continues online until 17 April, is focussed on illustrated magazines in the interwar period. In Britain, much of the academic work on this topic, at least in relation to popular titles, has considered the mainstream illustrated weeklies from mid-1930s on, and most notably Picture Post. But I have long been fascinated by Radio Times, the BBC’s weekly magazine which enjoyed a monopoly for broadcast listings.

From late October 1936, the ‘Television’ edition of Radio Times (which I believe was only around one-fifth of the copies printed each week, and only available in London) also included television listings and features, and these pages (available – albeit with significant gaps – via the invaluable BBC Genome) are an unparalleled source for understanding the early years of the new medium. Today, I want to muse a little about the only two pre-war covers of the magazine that featured television, published on 23 and 30 October 1936.

Having started in September 1923, by the mid-1930s Radio Times was an immensely successful weekly. Since 1933 the editor had been Maurice Gorham, previously art editor for the publication and later, briefly, controller of the television service when it returned after the war. The covers of the magazine in the mid-1930s, which deserve a detailed study in themselves, were a mixture of photographs of radio personalities and topical events as well as illustrations that were almost exclusively traditional in style. Most of the covers were printed in black and white but just occasionally, for example for Christmas or a royal occasion, a full-colour cover was rolled out.

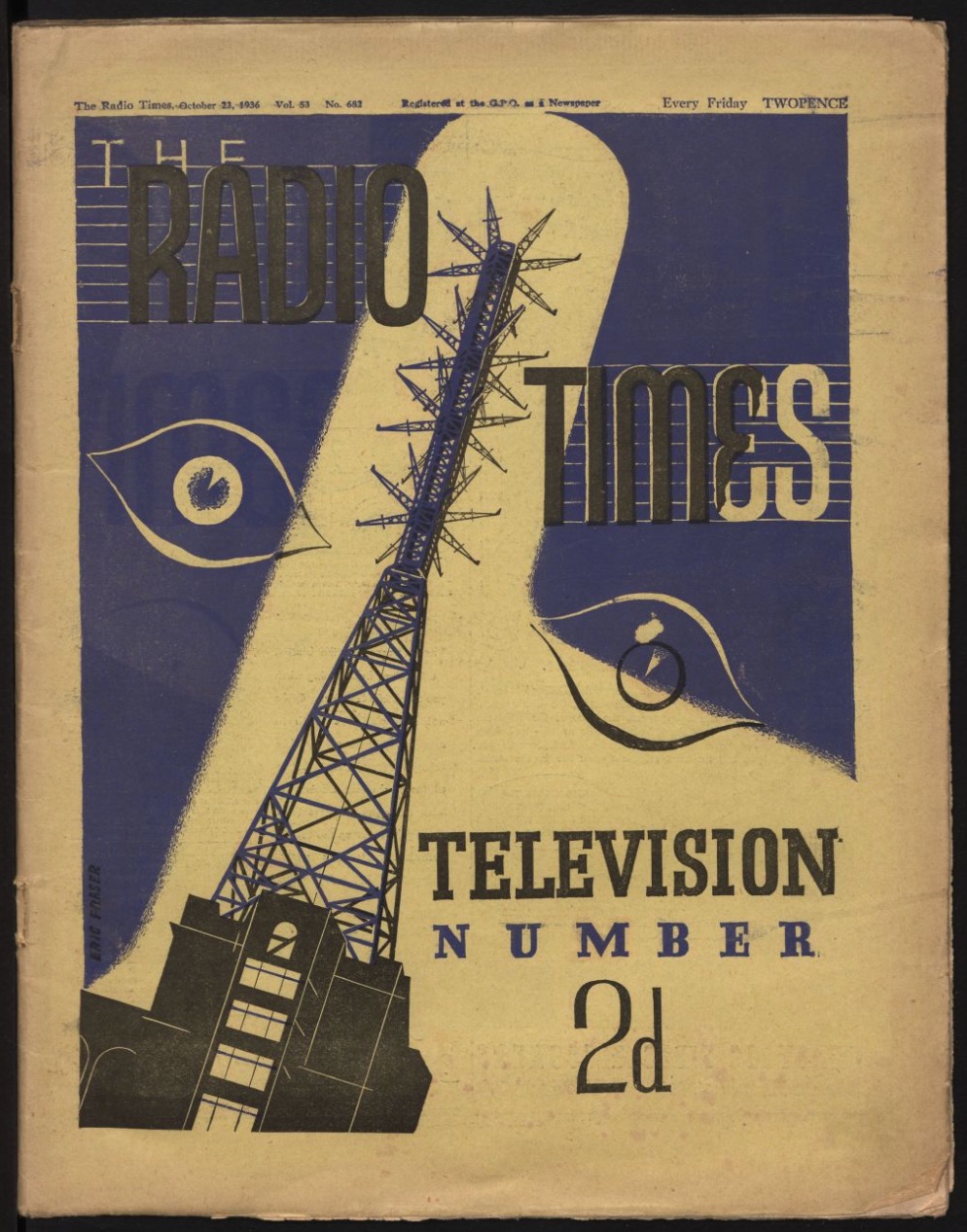

After several years of hosting late-night experimental transmissions by John Logie Baird’s company, the BBC was scheduled to begin regular ‘high definition’ (that is 405-line) transmissions from Alexandra Palace (AP) on 2 November 1936. The anticipated audience was to be in the hundreds or perhaps low thousands, almost all of whom would be within around 40 kilometres of the AP transmitter. Nonetheless there was huge public interest in the idea of television and the start of the BBC’s service was a historic event. So this is how Radio Times chose to mark the occasion, publishing this striking cover the week before programmes began.

The abstract design clearly echoes the advanced look of commercial graphics of the 1930s, examples of which can be seen in the modest online exhibit from the V&A, ‘Printing a New World’. Although this illustration carries no credit, the figure best-known for such work is the American graphic designer Edward McKnight Kauffer, who lived in London from the First World War until 1940. His posters for London Transport are especially celebrated. The angled lay-out and (I would argue, clumsy and uncertain) mix of typographic styles (including the Radio Times banner in eccentric sans-serif lettering; compare below for the usual form) are influenced by the ‘new vision’ forms of the European avant-garde associated with figures including artist László Moholy-Nagy and typographer Jan Tschichold. Their work had contributed to the visual modernism of weekly magazines across Europe, including VU in France.

The dominant element of the illustration is the silhouette of the transmission mast atop the east wing of AP. In 1935 the BBC leased space here for television studios and offices, and the new mast was adopted as a symbol of the new, modern (and in a way, invisible) medium. Indeed, the mast here, along with the design of the cover as a whole, speaks of the modernity of television, and by extension of the BBC as the nation’s broadcaster. The power of the mast, and of the BBC, is also suggested by being seen from below, with the angle conjuring up the dynamism of the corporation looking to the future.

Privileging the process of transmission, what the cover does not illustrate is any sense of the reception of television. There is no trace of a domestic receiver or of individuals or families gathered around a screen. ‘Looking-in’, as watching television was often called then, was an experience that very few Radio Times readers would have had at this point and it had yet to crystallise into a recognisable image. ‘Vision’, however, is strongly present in the wide-open, staring eyes — and is the placing of the mast, along with the white outlining, meant to indicate a human nose?

The eyes of the abstracted viewer, however, seem far from welcoming the reader in to a new world of visual delights. Rather, they are suggestive of surveillance, of a powerful (and perhaps coded female?) figure looking down from AP into the homes of those below. Which, of course, was one of the key fantasies and fears about the new medium of television — that it could look back into the home. All in all, then, the cover seems to me to speak of the ambivalence and uncertainty that the BBC, with its well-established and secure grounding in radio, felt about the upstart medium that it was, somewhat reluctantly, welcoming to the world.

Television also featured on the cover of Radio Times the following week, which is when broadcasts from AP actually began. The elaborate masthead was restored, along with the hopeful – albeit in late 1936, just months into the Spanish Civil War, ever more distant – statement of purpose ‘Nation shall speak peace unto nation’.

Normal service has, to a degree, been resumed. There is a single monochrome photograph of a BBC presenter, announcer Elizabeth Cowell. But again this is television production and not reception, with Cowell shown in the Baird company’s ‘spotlight studio’ at AP. (Baird’s system was being tried out along with a rival production process from EMI-Marconi; the Baird set-up was deeply flawed technically and was decommissioned in February 1937.)

There is, however, still a strong sense of modernity in the formal shapes within the photograph, with the technology and backdrop forming a geometric structure to the image, dwarfing and enclosing the human figure. Elizabeth Cowell herself has a slightly uplifted gaze, staring above and beyond what I take to be the bank of lamps on her left-hand side (the Baird system required intense light for its operation). It is almost as if she, like the mast the previous week, is looking to a brave new world that she believes – or hopes – will be ushered in on television’s ‘magic rays of light’.

Adele Dixon, from the 1936 documentary film Television Comes to London.

After I finished the post I found this great online gallery of ‘The Art of Radio Times’

https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/p01h96nf/p01gz2f9

From which I discover that the illustrator for the ‘Television Number’ was Eric Fraser, who contributed many, many drawings to ‘Radio Times’ over the years. Details of his life and a great selection of his other work can be found online at the Chris Beetles Gallery:

https://www.chrisbeetles.com/artist/27/eric-fraser-fsia

And I stumbled across a short film made for Arena in 1981 with and about Eric Fraser speaking especially about his illustrations for ‘Radio Times’:

https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/p01gwdnn