The language of lockdown 1.

John Wyver writes: Two months or so into lockdown I wonder if, along with so much else, we are seeing a fundamental shift in the screen language of our moving image media. So do I have your attention now?

I am struck by how quickly so much online performance, entertainment and drama has moved away from forms in which single screen images are predominant and on-screen space is constructed through sequential editing of supposedly contiguous shots. Instead, we are seeing the blossoming of innovative screen spaces with multiple images from separate real world or abstract environments proliferating within single frames.

As I’ll go on to explore in what I intend to be a series of posts, key influences here are our enforced use in professional and personal contexts of Zoom and the like, as well as the mainstreaming of super-smart Tik Tok videos. Another contributing factor, of course, are the constraints on conventional media production. Out of this nexus of challenges and opportunities is emerging what we might think of as the screen language of lockdown.

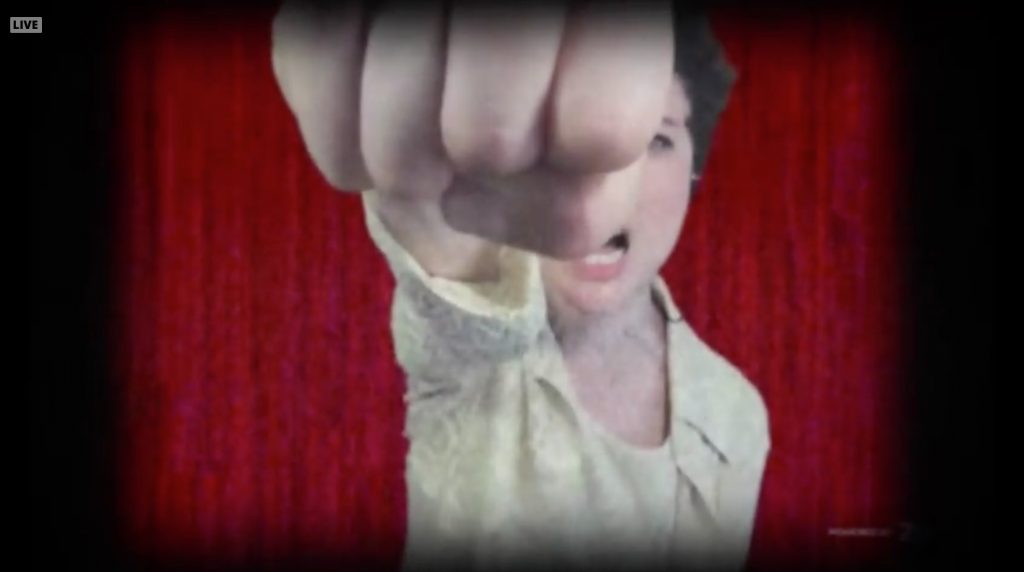

This past weekend saw the premiere of Illuminations’ modest contribution to this language with Unicorn Theatre’s Anansi the Spider Re-spun, episode 1: Brother Anansi and Brother Snake, a screengrab from which is above. Over the past weeks we have been working with the Unicorn’s artistic director Justin Audibert and his brilliant creative team to adapt for the screen the Unicorn’s hit show for 3-8 year olds. Our own Todd MacDonald collaborated as editor and technical director, and as yesterday’s 5-star review from Samuel Nicholls at A Younger Theatre recognised, the result is simply ‘an unbeatably fun and fresh experience’.

The first sense in lockdown I had of something new and different was from watching the socially distanced performance of part of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony from Rotterdams Philharmonisch Orkest. This went online on 20 March, and at the time of writing has clocked up 2.8 million views on YouTube and countless more elsewhere. It remains a heart-warming delight.

Since then, we’ve seen a host of variants, including this beautiful vocal work, 40 Parts for 40 Days, which features Stile Antico singing Thomas Tallis’ Spem in Alium.

Dancers quickly joined their musician colleagues with the Ballet de l’Opéra national de Paris working with director Cedric Klapisch to make the astonishing – and astonishingly beautiful – “Dire merci” (online 16 April). If you haven’t already seen this, do stay to the end…

Among the very finest — and most complex — of these screen space classical performances is the glorious Bolero from The Juilliard School (online 30 April), the making of which is discussed here.

Drama too has embraced the language of split-screen space, with one strategy being the explicit use of Zoom calls as the context in which a narrative is developing. The hilarious Initial Lockdown Meeting from the cast and scriptwriter of W1A is perhaps my favourite example to date:

Theatre companies have also been exploring the screen space of Zoom as a performance arena, as Peter Kirwan has described in his invaluable Bardathon reviews of The Tempest (Creation/Big Telly Theatre) @ Zoom and As You Like It (CtrlAltRepeat) @ YouTube and as Ben Broadribb and Gemma Allred have been documenting so productively at the ‘Action is eloquence’: Re-thinking Shakespeare blog; see especially their jointly authored Lockdown Shakespeare: the state of (the) play.

The most exciting and rewarding use of a live split-screen space that I’ve experienced so far was last Wednesday’s presentation by Theatre for a New Audience and Fisher Centre at Bard of Caryl Churchill’s Mad Forest. Directed for a specially modified version of Zoom by Ashley Tata, this was a gloriously inventive production discussed in The New York Times by Ben Brantley. There were only three live webcasts and – presumably because of copyright restrictions – there is no online recording, but hopefully these screenshots can give a sense of the 1 hour 40 minute show. You can also download the digital programme here.

For further context, see the Mad Forest tumblr page, which features a number of really interesting how-we-made-it videos, and Victoria Mescall’s feature for American Theatre.

There’s much more to say about this Mad Forest – and I very much hope that the production develops and returns – but as I watched, despite (or in large part because of) the technical glitches and the raw aesthetic, I felt that I really was seeing the rapid development of a new form. I had a notion that this was just as I might have felt had I sat in a Nickelodeon around 1908 or crouched before a flickering television broadcast from Alexandra Palace some thirty years later.

Clearly the use of split screen images is far from unprecedented in cinema and television, and my next post will look at some of the precursors. But the contexts in which they have been used have for the most part been limited, as in news and sports broadcasting on television and as somewhat exotic visual spectacles in mainstream movies like Grand Prix (1966) and Scott Pilgrim vs. the World (2010). What we are beginning to see in this new language of lockdown feels different, and the reasons and implications of this I’ll endeavour to tease out in future posts. Needless to say I would welcome discussion of this, as well as additional examples and references to other places where this is being discussed.

You’re definitely onto something there, John, and I’m thinking about it in relation to Mike Figgis’ experimentation with split screens in Miss Julie, Timecode and Hotel, as well as the split screen work that we’re now getting access to from Europe: I’m thinking here in particular of Toneelgroep Amsterdam’s really rather astonishing use of split screens for their recording of The Taming of the Shrew/Temmen van de feeks which is available here: https://www.vpro.nl/speel~WO_VPRO_012300~temmen-van-de-feeks-cultura-toneel-op-2-making-of~.html. Evidently, split screen aesthetic is used in the stage production itself, with its multiple sets, but it’s used creatively in the screen version, too, with some rather brilliant effects to create ‘noise’ both visually and aurally, as when the wedding party guests go wild, Katherine in one quarter of the screen holds her ears, and then the screen changes to just the close-up of her as she’s fighting off the noise. The effect is as if you were pulled into her headspace and away from the people who create the noise, so that the screen audience is associated with her against the people who torment her. So it’s not just used to represent the simultaneous action that is happening on different stages at the same time, but also interpretively. There are lots of other examples there.

The other European production that I’m thinking about in relation to zoom/split-screen aesthetic is Grzegorz Jarzyna’s Macbeth: 2007, precisely because the camera work for the first half of the broadcast carefully avoids creating split-screen effects even if, as becomes obvious when finally a shot of the whole stage clarifies the relationship between spaces, the set was actually made up of at least four distinct spaces: a big hangar-like double-floor space on the left, some narrow corridors in the middle, and on the right a downstairs room leading off into a half-visible offstage room, and upstairs a balcony with multiple video screens. So what you had there was a production that was using split-screen effects as simultaneous action was taking place on different parts of a vast single set, but in the broadcast that was turned into realistic TV-style camera work taking you inside one part of the set after another, with cuts between spaces, as if it was moving between sound stages. It came as a relief to suddenly see the whole set and I’m wondering whether there was an anxiety on the part of the broadcast team about using split screens, since this was recorded *before* the age of Zoom. I suspect that now, they might have taken a different approach as we’re all much more literate in terms of split-screen language.

What interests me in all this is that there is evidently a confluence of stage and screen work here and remediation in both directions: stage work that (like Katie Mitchell’s) uses ‘filmic’ language, conventions, set design and media, and now it’s new broadcast work that is responding to such work in a way that mirrors it and builds on it.

This is all very off-the-top-of-my-head and not properly worked through yet, but I did want to respond to your blog since I’m thinking along similar lines, but in an adjacent part of the field.

Apologies: I think I sent the wrong link for Temmen van de feeks. Here it is: https://www.vpro.nl/speel~VPRO_1134550~temmen-van-de-feeks~.html . Enjoy! (watch out, too, for the three-way split screens and the really disturbing two-way split between Katherine and Petruchio in the aftermath of what I will forever more think of as the ‘weeing scene’).

Thank you John for such an interesting post – and thank you Pascale for such an interesting comment. I’m excited about watching Anansi with my daughter! A very off-the-top-of-my-head comment — I was totally blown away by the Opera de Paris video, and then the Julliard one too. I’m sure a huge part of this is the fact that they’re just so good in terms of their filmmaking. But they also made me wonder if certain art forms really shine in this medium — specifically dance. The Julliard features musicians and actors too, but it was the dancers that really captivated and moved me. Maybe it’s just me…. but it did make me wonder if 1) the sight of the body in motion has particular power in the stasis of lockdown, 2) we are a bit oversaturated with words in the midst of so many Zoom calls, emails, chats, etc., and 3) the formal structure of the multi-windowed screen is at its most powerful when it’s framing something fluid and dynamic.

I think you are onto something, Erin! What is so exciting about the dance examples is that they use a form – videoconferencing – for a different purpose than the one it was designed for and in doing so, they seemed to “bend” the squareness of the screen as a sort of détournement. And that, in turn, is doubled by the formality of dance technique which is “bent” into something more humane by the insight (literally) afforded into the dancers’ homes, lives, family, individuality. For me, the power resided in this tension and in the way that clip remediated the fragmentation of the dance troupe from unified, profoundly disciplined and uniform movement into the individuality and paradoxical freedom of lockdown where every member of the troupe got to be and dance themselves.

Thanks, Erin and John, for pushing me into articulating some of this: it’s helpful to try to explain what I’m seeing, however obscurely.