15th June 2025

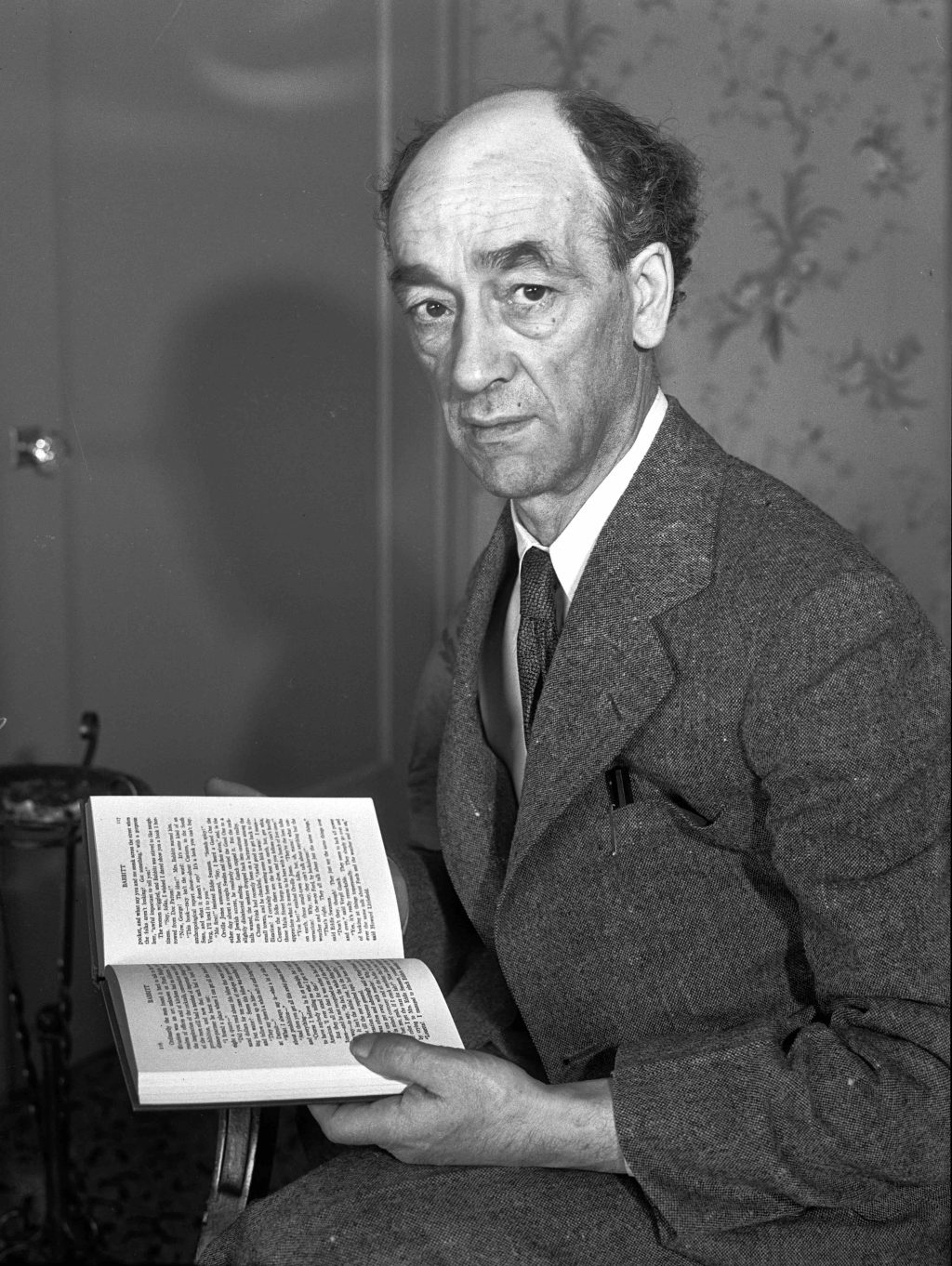

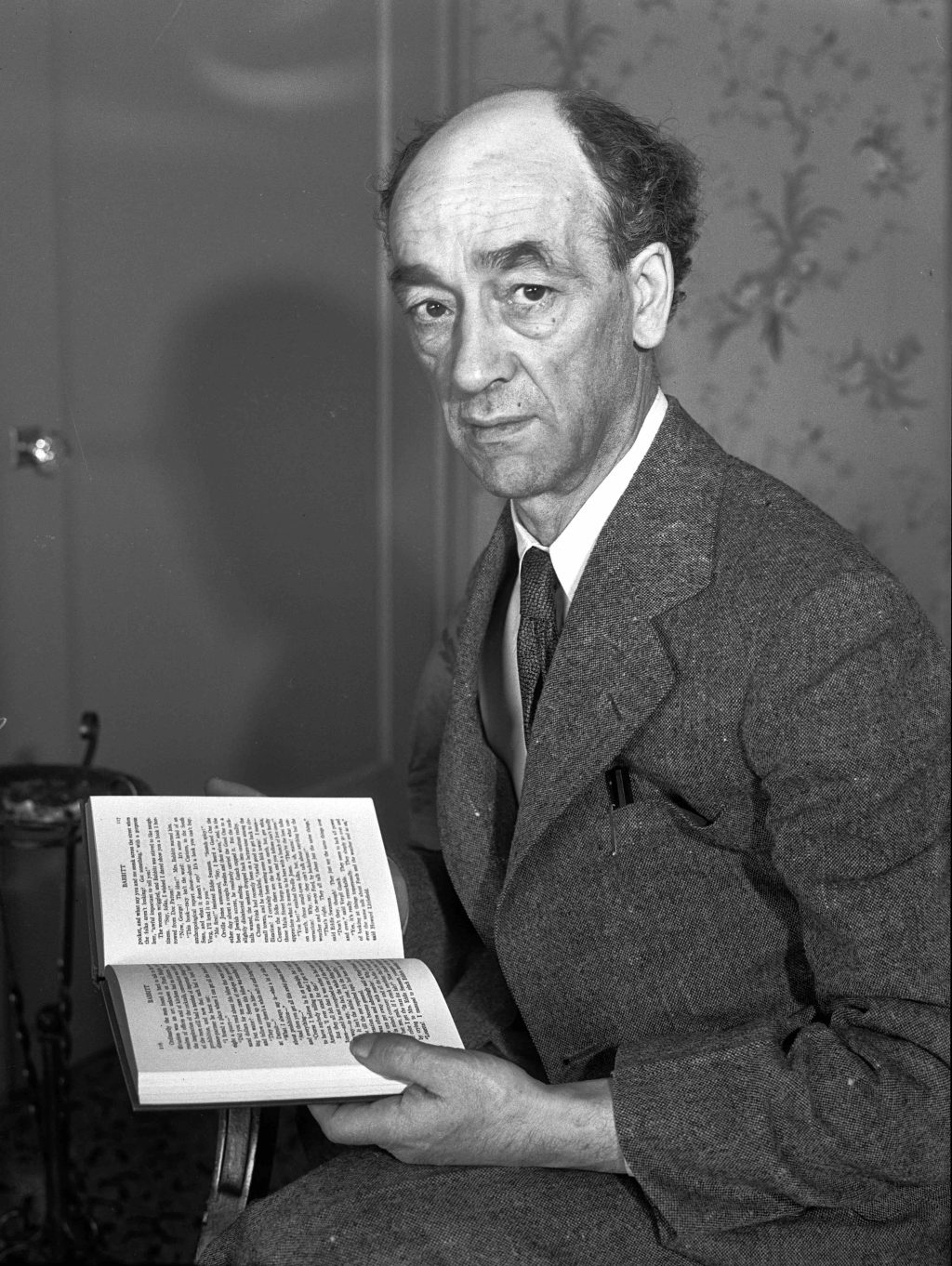

John Wyver writes: There are notes about pre-war television broadcasts when a historian looking back can only respond with an exclamation of something like ‘WTF’. One of those has to be a 12-minute studio talk on the evening of Tuesday 15 June 1937 about ‘The Future of Television’ given by the Irish writer James Stephens (above).

Talks producer Mary Adams was only two months into her job when she started this series in April with Megan Lloyd George in the studio. Gerald Barry, editor of the News Chronicle, had contributed his thoughts, as had the writer S.P.B. Mais. But what was she thinking of when she booked the Irish mystical poet Stephens?

A committed Irish Republican, author of the influential account of the 1916 Easter Rising, Insurrection in Dublin, Stephens became a close friend of James Joyce. At one point, when he was concerned that he might not be able to complete what became Finnegan’s Wake, Joyce apparently proposed that he should collaborate on it with Stephens.

Stephens made a number of radio broadcasts in the late 1920s and early 1930s speaking about poetry, but there appears to be little in his biography that suggests he had interesting views about television. Frustratingly, we have no script of what he offered, apart from the fact that he concluded with a recitation of five of his poems including ‘The Main Deep’ and ‘The Voice of God’. Which in 12 minutes cannot have left much time for tackling the future of the medium on which he was speaking.

Image: Portrait of James Stephens in 1935 by Los Angeles Times – licenced CC BY 4.0. (Forgive the large size – I just think it’s a great photograph.)

[OTD post no. 180; part of a long-running series leading up to the publication of my book Magic Rays of Light: The Early Years of Television in Britain in January 2026.]

14th June 2025

John Wyver writes: Monday 14 June saw two studio performances of the second part of James Elroy Flecker’s Hassan, following on from the previous Tuesday’s opener. The staging was the next recognised television drama landmark after the December 1936 presentation of Murder in the Cathedral, and was hailed as a major step forward for the fledgling art.

Drama producer George More O’Ferrall, who had handled Murder…, was sufficiently confident to attempt a lavish studio presentation, including incidental music by Delius composed for the play’s premiere in 1923 and played here by the BBC Television Orchestra.

read more »

13th June 2025

John Wyver writes: For the best part of an hour on the afternoon of Monday 13 June 1938, Alexandra Palace offered an OB from Northolt, just over a dozen miles away. The occasion was the running of the Northolt Pony Derby, one of the few horse races not under the control of the Jockey Club and as a consequence available to television. Only for the Epsom Derby were rights otherwise granted to television.

The story of the Northolt race course and of interwar pony racing is laid out in a fascinating and beautifully illustrated online history written in 2017 with, as far as I can see, no byline. As the writer explains,

Pony racing had been in existence for centuries in various parts of the country, but was not well regulated and had a serious reputation for cheating and corruption. In an attempt to organize and gain respect for the sport, the Pony Turf Club (PTC) was formed in 1923 and was subsequently recognized by various bodies as a legitimate regulated sport.

The intent of the PTC was not only to provide venues for smaller horses to race, but also to satisfy the racing and betting needs of those with more ‘limited means’. This meant admission fees that were significantly less than those at established horse racing venues, but with facilities of a much higher standard, in an attempt to attract more female supporters.

read more »

12th June 2025

John Wyver writes: As the 30-line service under producer Eustace Robb moved towards its final broadcasts in early September 1935, the offerings became increasingly eclectic and distinctive. On the evening of Wednesday 12 June 1935, a 55-minute transmission was billed as ‘A recital of folk songs and dances from India, Ceylon and Tibet’.

Along with the Sinhalese singer Surya Sena, assisted by Nelun Devi (already the joint subjects of an earlier OTD), this late-night programme also featured the only British television appearance by American dancer Ted Shawn and his all-male company.

read more »

11th June 2025

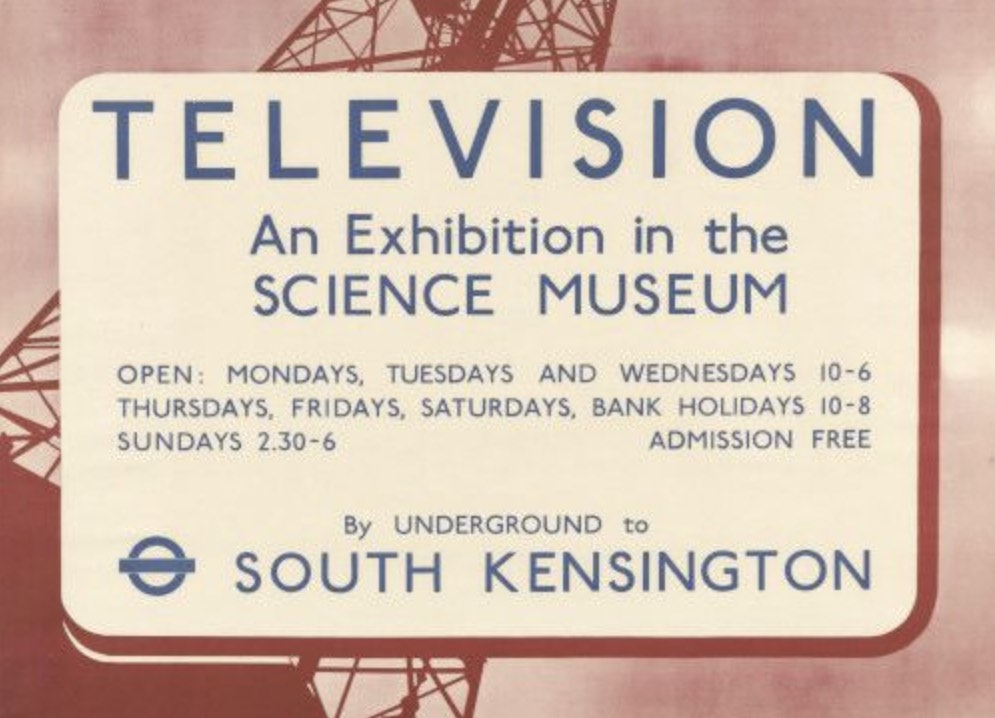

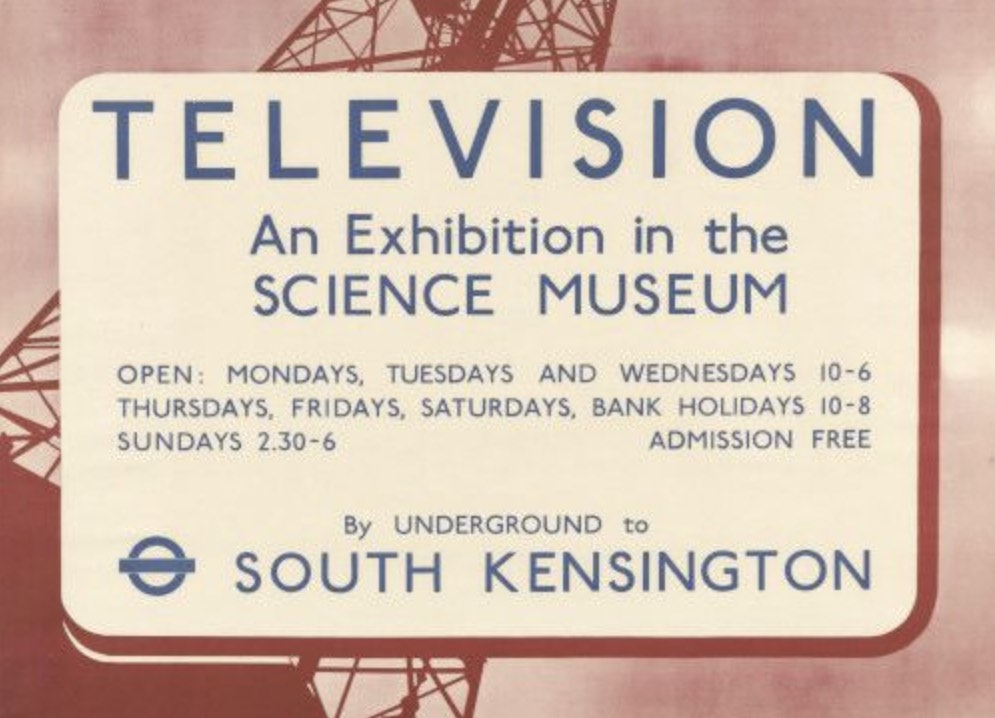

John Wyver writes: Friday 11 June 1937 saw the nation’s broadsheets carry news of the opening the previous day of an exhibition of television at London’s Science Museum in South Kensington. Television in the summer of 1937 was still a more common spectacle in department stores and pubs than in homes. And it was extended as a public form in this hugely popular presentation.

As the Manchester Guardian reported:

The BBC, the leading manufacturers, and the science museum have organised the exhibition, and its objects are to illustrate the general principles underlying technicalities and to foster appreciation of television as a home entertainment.

In fact, the Science Museum offered a last hurrah for showcasing television’s origin in the workshop and its identity as a technological wonder. In future exhibitions, such as Radiolympia later in the year and in the 1938 Ideal Home Exhibition, it would be celebrated more as a medium and as an element of domestic modernity.

read more »

10th June 2025

John Wyver writes: On the evening of Friday 10 June 1938, studio A at Alexandra Palace hosted artist couple John Piper and Myfanwy Evans presenting A Trip to the Seaside, a short talk about ‘things seen during a recent visit to the seaside’. Included were paintings and drawings by Piper and by their friends Paul Nash and Edward Wadsworth, as well as poetic extracts from Max Beerbohm’s ‘The seaside in winter’, John Meade Faulkner’s ‘Moonfleet’ and, perhaps inevitably, ‘Dover beach’ by Matthew Arnold.

John Piper had been a regular AP presenter in the first months of the service, introducing paintings and sculptures borrowed from London’s commercial galleries. Myfanwy Evans had also appeared on screen before, just once in July 1937, when she recounted a bicycle journey through the Chilterns, which was also illustrated with photographs and articles found along the way.

read more »

9th June 2025

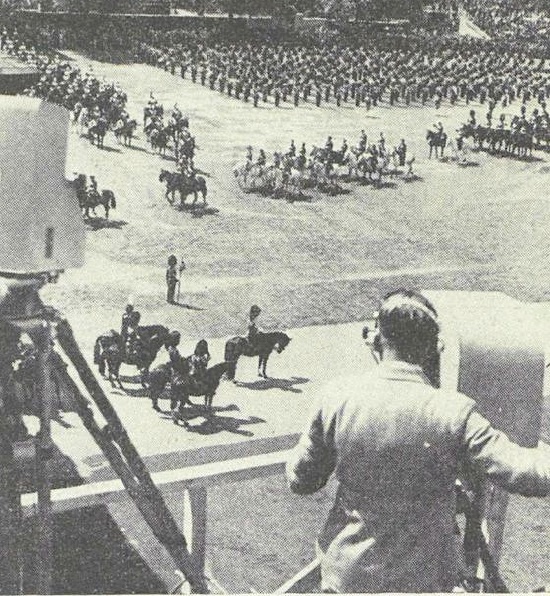

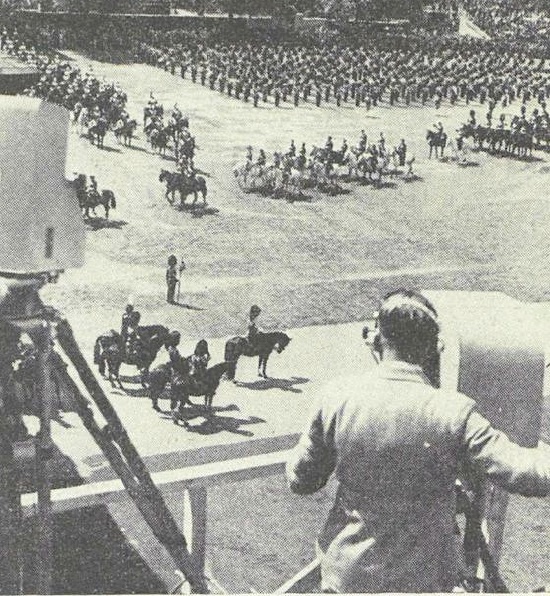

John Wyver writes: On the morning of Thursday 9 June 1938 the BBC’s mobile control room provided an 80-minute outside broadcast from Whitehall of the King’s Birthday Parade, otherwise known as Trooping the Colour.

This was just over a year after the first remote OB of the Coronation procession in May 1937, and the novelty, as well as the reverence for the monarchy, are apparent in the detailed description by Peter Purbeck writing for The Listener.

Purbeck’s words below about the predictability of the event and the importance of this for the OB producer make for an interesting contrast with Grace Wyndham Goldie’s description of the OB from the Theatrical Garden Party of a year later, which was highlighted in a post here a few days ago.

read more »

8th June 2025

John Wyver writes: Under the bare title of A.R.P., a 14-minute studio programme on the evening of Wednesday 8 June was ‘a demonstration of the use of gas masks’. Sandwiched between a newsreel and the cartoon film Mother Goose Melodies, this had been ‘arranged in co-operation with the Home Office’ and appears to have been the first public information broadcast preparing lookers-in for the anticipated international conflict.

We know little about the broasdcast, apart from that it featured the splendidly named Flight Lieut. Eardly-Wilmot, Mrs Caillard, and Messrs Bowen, Thistle and Radcliffe, and that use was made of two British Movietonews film extracts, ‘Airplanes’ and ‘A.R.P. work street sequence’.

Later in June, the Flight Lieutenant and Mrs Caillard returned to AP to demonstrate how to gas-proof a room, and in October there was a spectacular broadcast showing recommended methods of dealing with an incendiary bomb.

Image: ‘Fitting Anti-gas Clothing’ by Jane Stanton, date unknown; a Sergeant of the Women’s Royal Army Corps helps to fit a gas mask to a recruit; from the collections of the Imperial War Museums. Scanned and released on the IWM Non Commercial Licence. Photographs or artworks created by a member of the forces during their active service duties are covered by Crown Copyright provisions. Faithful reproductions may be reused under that licence, which is considered expired 50 years after creation date.

[OTD post no. 173; part of a long-running series leading up to the publication of my book Magic Rays of Light: The Early Years of Television in Britain in January 2026.]

7th June 2025

John Wyver writes: Seven months after the start of the schedule from Alexandra Palace, on Monday 7 June television’s offerings were a typical mix of, in the afternoon between 3pm and 4pm, a local OB, a newsreel and an upscale variety line-up, followed by an evening hour from 9pm of a short studio feature, a recital, another newsreel, and the BBC Dance Orchestra in concert.

There was no sense of building a schedule across either session, and no links between the disparate elements. By this point there were perhaps a few hundred operational receivers across London, many of which were in dealers’ showrooms, and the twice daily priority for the over-worked, resources-starved AP producers was simply to get something, anything, onto the airwaves.

read more »

6th June 2025

John Wyver writes: For the best part of an hour on the afternoon of Tuesday 6 June 1939 lookers-in were taken off to the gardens of the Ranelagh Club for the annual Theatrical Garden Party. Among those who were observed and encountered were Noel Coward, Ivor Novello (above, with Leslie Mitchell), Diana Wynyard and playwright Clemence Dane.

Also making appearances were Telegraph journalist L. Marsland Gander; Mrs Smithers, recorded as ‘a member of the public’; ‘a lady viewer’; and Euphan MacLaren’s children. No, me neither, but Ms MacLaren apparently ran a stage school for young people , but it’s unclear if the children were offspring or pupils.

read more »