17th April 2016

Next Saturday, 23 April, I am one of the producers on the Royal Shakespeare Company-BBC collaboration Shakespeare Live! From the RSC. It is going to be a great show, and you can see it at 8.30pm on BBC Two and in cinemas. But it is not leaving me much time to post, apart from this further set of links to stuff that I have found interesting in the past week.

• In excess of the cut – Peter Greenaway’s Eisenstein in Guanajuato: a really good piece by David A. Gerstner for Los Angeles Review of Books on one great director’s take on another (above), released in cinemas and for VOD this week. read more »

10th April 2016

Links to interesting stuff from the past week.

• How offshore firm helped billionaire change the art world for ever: the first of two stories about what the Panama Papers reveal about the high end of the art market, this from the Guardian team…

• The art of secrecy: … and this from the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists – the articles are complementary, and compelling for anyone interested in auctions, galleries and collectors. read more »

9th April 2016

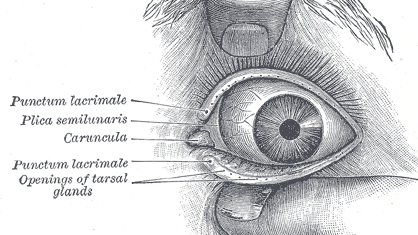

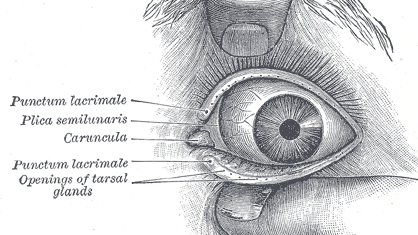

I am fascinated by the history of early experiments towards television, including those made by one of the key pioneers John Logie Baird. One of the strangest tales that I have just been reminded of in my reading today concerns the inventor’s encounter with a human eyeball. Ninety years ago, in the spring of 1926, Baird was struggling to get the photocell technology he was using to achieve sufficient sensitivity to light. As his wife Margaret recorded Baird recalling in her 1974 memoir Television Baird, read more »

8th April 2016

Given the dismal state of television criticism in this country, I guess I should not be surprised that BBC Two’s Inside Obama’s White House has not attracted more thoughtful attention than it appears to have done to date. For the Guardian Mark Lawson wrote a typically thoughtful and well-informed piece about the series and access documentaries and Philip Collins contributed an appropriately enthusiastic piece for Prospect: ‘journalism of the highest calibre’. Daisy Wyatt in the Independent was won over but Christopher Stevens for the Daily Mail dismissed the first episode as ‘dull… no plot, no tension, no good lines’, and I can find little else that engages in any detail with what for me is a really remarkable achievement. read more »

7th April 2016

Some of today’s richest and most stimulating research projects in cinema and media studies have at their heart the tools of data analytics. And Marina Hassapopolou at the NYI Center for the Humanities has just put online a highly informative blog post that is a great introduction to the range and breadth of this cutting-edge work. The works cited in her piece are a good place to begin exploring further, as is the website for an upcoming conference in New York, Transformations I. The sub-title for the conference in mid-April is ‘Cinema and media studies research meets the digital humanities’, and while the full programme is not yet available there is a good reading list and an invaluable listing of relevant research projects, most of which have substantial online presences. I am only barely literate in this field but I intend to try to educate myself further by tackling some of this reading and engaging with a number of the projects over the coming weeks, and I’ll aim to post reflections.

read more »

6th April 2016

So just what seems to be the problem? We have a shiny new web site which, while far from perfect, is a big step on from what was here before. While we were working on how to structure the new site I argued strongly for keeping this blog somewhere near the centre. But now the blog is here I’m not completely certain what or how to post. There are many things I want to share and comment on, and (but?) I do that on Twitter all the time. Then there are things that I want to reflect on at length, had I but world enough and time. Even so, I seem to find time to do that in occasional essays and articles. But so far, apart from faltering steps towards re-starting Sunday links, I am neither sharing nor commenting nor reflecting here with any consistency. As a songsmith who never seemed to suffer from writer’s block once wrote, ‘Why an’ what’s the reason for?’*

read more »

3rd April 2016

Now, with some post-Dublin additions…

• The art of being in the wrong place at the right time – behind the scenes of social media newsgathering: a remarkable reflection by David Crunelle from medium.

• Lost in Trumplandia: the fascination remains despite the horror, the horror, so here’s a very good piece for New Republic by Patricia Lockwood, with some fine photographs by Mark Abramson.

• Julius Caesar, 1908: it’s frustrating that that BFIPlayer has entirely superseded the BFI posting films to Youtube, not least because it prevents embedding, but here is a link to a wonderful silent Vitagraph condensation of Shakespeare’s play.

• Rétrospective Raoul Ruiz: La Cinémathèque française has launched a great tribute to the late much-lamented director (until 30 May), and even if you can’t get to Paris for that, the trailer for it is a thing of beauty.

read more »

29th March 2016

Just released on DVD and Blu-ray by BFI Publishing are two sets of dramatised biographies made by Ken Russell at the BBC in the 1960s. The Great Composers contains Elgar (1962), The Debussy Film (1965) and Delius: Song of Summer (1968), while The Great Passions features Always on Sunday (1965), about the painter Henri Rousseau, Isadora: The Biggest Dancer in the World (1966) and Dante’s Inferno (1967), featuring Oliver Reed (above) as Dante Gabriel Rossetti. The appearance of these films, several of which have not been available on home video before, is hugely welcome, since they are both enormously enjoyable (even if I have reservations about aspects of them) and key documents of British television and pop culture in the 1960s. read more »

27th March 2016

A time there was when very Sunday morning I contributed a list of reading and viewing that I had found interesting during the previous week. To mark this blog rising once again from decrepitude, here is a selection for today. read more »

26th March 2016

One of the most interesting strands of moving image criticism today is the the fast-developing form of the short audio-visual essay. Made possible by the availability of films on DVD and as downloads, by desktop editing systems, by “fair use” copyright provisions as long as the result is for criticism and study, and by film scholars increasingly adept at the techniques of those they study, these essays can be rich and resonant. As is today’s example: Visconti: Art and Ambiguity, made by Pasquale Iannone, a specialist in Italian cinema, for the US-based arthouse streaming service Fandor.

read more »