Earl Cameron and a lost play

John Wyver writes: Back in October 2018 I was fortunate to see Basil Dearden’s 1951 luminous crime drama Pool of London at BFI Southbank. What made the occasion particularly special was a gracious introduction by one of the film’s stars, the great – and now late – Earl Cameron (above). His death at the age of 102 was announced last week, and among the tributes are Brian Baxter’s Guardian obituary and the Tweets in a BBC News story. Pool of London is a truly exceptional post-war British movie, which can be viewed via BFIplayer for a modest fee, and I recommend it warmly.

Coincidentally, on Friday, while working towards a documentary about the BBC1 series Play for Today (1970-84), about which I’ll write (much) more later, I stumbled across a trace of one of Earl Cameron’s later performances. In 1968 the actor took a leading role in a BBC2 production for the Theatre 625 strand of Wind Versus Polygamy, a play I’d not heard of by a writer, Obi Egbuna, of whom I was similarly (shamefully) ignorant. Following up on this sent me down a research rabbit-hole to encounter the Pan-African Players, the British Black Panther Movement and the complexities of the politics of race in late 1960s Britain. From which has come this first element of a two-part post, the conclusion of which will follow later this week.

Wind Versus Polygamy on television and radio

Looking into the productions for the Play for Today strand in its first years, I was surprised to find that in March and April 1971, starting just five months after the series launch on 15 October 1971, seven dramas from other series were repeated with Play for Today titles. In Radio Times these ‘Play for Today: Seven Selected Plays’ were listed as Alan Plater’s No Trams to Lime Street (11 March 1971, links to BBC Genome listings), Mad Jack by Tom Clarke (18 March), Barry Bermange’s Scenes from Family Life (25 March), Wind Versus Polygamy by Obi Egbuna (1 April), Johnny Speight’s Playmates (8 April), Don Shaw’s Sovereign’s Company (15 April) and Season of the Witch (22 April), a tale by Desmond McCarthy and Johnny Byrne with music by Brian Augur and the Trinity.

Sidebar 1: for more on Play for Today, see the long-established British Television Drama web site and the brand new Play for Today at 50 section of the Forgotten Television Drama website. David Rolinson’s introduction at the former and the latter’s overview by John Hill will together give you an excellent introduction to the series, and you can follow them up with Simon Farquhar’s newly published discussion of one of the earliest Plays for Today, The Right Prospectus written by John Osborne.

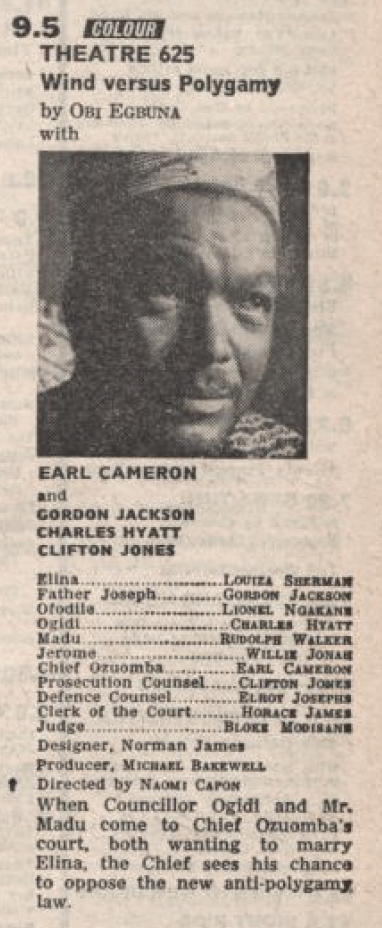

Six of the 1971 repeats are titles that are recognisable from The Wednesday Play (1964-70), the BBC1 strand of single dramas that preceded Play for Today. Egbuna’s Wind Versus Polygamy had also been shown as a drama for The Wednesday Play, on 27 May 1970, but it had originated in the BBC2 series Theatre 625 where it was first transmitted on 15 July 1968. In Radio Times on its first transmission, the play is described as ‘a charming story from Africa’ (11 July 1968, p. 3) and while there is no associated feature, there is a detailed listing with an image of Earl Cameron in the lead role of Ozuomba.

As can be seen from the listing, the cast also included the Trinidadian actor Rudolph Walker, best known now for playing Patrick Trueman in EastEnders since 2001, and and the Jamaican actor and playwright Charles Hyatt, as well as Gordon Jackson, who was later to be celebrated as the butler Angus Hudson in Upstairs, Downstairs. The producer was head of plays Michael Bakewell and it was directed by the stalwart Naomi Capon.

Two years before this television production, the Home Service mounted Charles Lefeaux’s audio production of Wind Versus Polygamy, broadcast on 11 July 1966 (see below). Earl Cameron also took the role of Chief Ozuomba in this vesion. Added to the three television broadcasts (at a time when repeat showings were comparatively rare), this means that Egbuna’s play had a significant presence in BBC drama in these years, which is all the more notable given that it is one of the earliest radio or television plays by a Black writer.

In The Listener David Wade (21 July 1966) was unimpressed by the Home Service production: ‘ the subject was treated in that wooden tractarian style which subordinates character to message. As a result, even so good an actor as Earl Cameron sounded uneasy with his lines.’ I have not yet found a substantial review of the television production, but this is how Elkan Allan described it when previewing the Play for Today repeat (Sunday Times, 28 March 1971):

a gentle tale of changing Africa by Obi Egbuna, who started the British end of the Black Panther movement and received a three year suspended sentence for uttering a document on killing policemen. All this might have made a more gripping play than this wayward comedy.

Which is, of course, a more-than-intriguing taster for where this story is taking us.

Obi Egbuna, playwright

Wind Versus Polygamy was first published as a short novel by Faber and Faber in the autumn of 1964. The reviews were respectable if on occasion patronising; this anonymous notice in The Times (26 November 1964), referencing Harold MacMillan’s 1960 ‘Wind of Change’ speech, is typical:

‘The Wind’… is the ‘Wind of Change’ and the title, weird at first sight, is actually apt enough, since much of a slight little book is concerned with a trial which sees the officialdom of a new African state, representing ‘the wind’, prosecuting a benevolent tribal chief who believes in the old ways and the virtues of polygamy. You must not, says the chief at one point, equate simplicity with primitivity’. Mr Egbuna does his best to avoid the trap.

In a discussion of Igbo novelists (included in European-language Writing in Sub-Saharan Africa, edited by Albert S. Gérard) Alain Severac is more enthusiastic about the book:

Wind Versus Polygamy… diverges markedly from the pattern set by Chinua Achebe and soon to be followed by the majority of Igbo novelists. It is a humorous tract against the enforcement of monogamy among the polygamous Igbos. Egbuna spares us the tediousness which often attends on polemical writing by inventing a tightly-knit plot and enlisting the support of comedy and suspense.

Born in Nigeria in 1938, Obi Benue Egbuna (according to Wikipedia) studied in the United States before moving to London in 1961, where he was to live for twelve years. By early 1966 Wind Versus Polygamy had become a drama and its production by the Pan-African Players was invited to the First World Festival of Negro Arts held in April in Dakar, Senegal. This was a large-scale gathering with more than 2,500 participants from 45 countries, and the United States sent Duke Ellington and the Alvin Ailey dance company. Britain’s contribution was rather more modest, comprising Wind Versus Polygamy and a jazz adaptation of the Passion Play, The Dark Disciples, by the Negro Theatre Workshop.

Sidebar 2: just before the journey to Dakar, a version of The Dark Disciples was broadcast on BBC1 in the religious series Meeting Point. Shown at 6.15pm on Passion Sunday, 3 April 1966, and repeated at 10.45 that evening, The Dark Disciples was shown live from the Church of St Mary-le-Bow in London in a broadcast devised and produced by Christian Simpson. Simpson is a fascinating figure in post-war television whose work deserves to be deeply researched (which I hope one day to undertake).

In a fascinating recent article in Research in African Literatures (50:2, Summer 2019), ‘Culture, Race, and the Welfare State: The British Contribution to the 1966 First World Festival of Black and African Culture’ (frustratingly pay-walled on JStor), Ruth Bush explores the British contribution to the Dakar festival, writing:

Britain’s contribution to Dakar ’66 was symptomatic of a post-war zeitgeist shaped by decolonization, British race relations legislation, and the ongoing sociocultural dynamics of Empire. It involved cultural institutions such as the British Museum, the BBC, and the nascent Arts Council. The British organizing committee for the Dakar festival depended on these pillars of the post-war liberal establishment, providing an unprecedented opportunity for black artists and performers (several of whom were first-generation Windrush migrants from the Caribbean) based in the UK to gain professional recognition, visibility, and connections on the African continent forged through firsthand experience… Dakar ‘66 tackled the… question of how to represent post-imperial Britain on an international, pan-African stage.

Bush concentrates in her article on the work of the Negro Theatre Workshop (NTW) and draws on the papers of the group held at the George Padmore Institute. NTW was founded in 1961 by Pearl Connor-Mogotsi, a central figure in the development of Black arts in Britain, and the company’s productions are referenced in, for example, in Natasha Bonnelame’s ‘Black British theatre: 1950-1979’ online from The British Library, and in Colin Chambers’s online essay ‘Black British Plays Post World War II -1970s’ for the invaluable National Theatre Black Plays Archive. The Archive’s catalogue ‘for the first professional production of every African, Caribbean and Black British play produced in Britain’ does not, however, include Wind Versus Polygamy, seemingly because no London presentation of the Pan-African Players version can be traced and because, apparently, the catalogue doesn’t embrace professional productions for BBC Television.

Ruth Bush notes in her article that the Pan-African Players were ‘a group led by London-based Sierra Leonean playwright Yulisa Amadu Pat Maddy that has left little trace’. Certainly there are no records comparable to the NTW archive, and Colin Chambers writes that Wind Versus Polygamy was the group’s only show. But we know from a Sunday Times diary item (6 March 1966) that the company that went to Dakar included Valerie Murray, Pearl Prescod and… Earl Cameron.

By this point Obi Egbuna had also started to contribute occasional book reviews to the Sunday Times, and he had become increasingly involved in political activism, a journey celebrated by his son, Obi Egbuna Jr., in a 2014 interview in the San Francisco Bay View National Black Newspaper, ‘Looking at the life of freedom fighter Obi Egbuna Sr.’:

My father’s political career started when he came to the U.K. with his heart set on becoming an electrical engineer, and, like the great lawyer Charles Hamilton Houston who taught Thurgood Marshall, realized he must become a social engineer. That concept and approach to struggle for daughters and sons never grows old, because our former colonial and slave masters want us to abandon social science altogether. This means we will never overcome mental enslavement and bondage.

My father realized the ships of our cultural and political armies must sail in the same direction. It started when he became a member of the Universal Colored Peoples Association. He wrote the Black Power Manifesto and after Kwame Ture’s visit to the Dialectics of Liberation conference, the Black Panther Party was officially launched in Britain. This was only three years after my father wrote Wind Versus Polygamy.

I’m going to continue the story of Obi Egbuna in a subsequent post, talking about his activism, arrest and detention for nearly six months without trial, but for the moment let me add three footnotes. The first is this BBC photograph of Egbuna in a radio studio with Peggy Ashcroft (reproduced from the Bay View article). Ashcroft is not listed in Radio Times as being associated with the Home Service production of Wind Versus Polygamy, and the date and occasion of this image are currently unknown (any additional information would be gratefully received).

Obi Egbuna’s papers are held by The New York Public Library Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Manuscripts, Archives and Rare Books Division, and a detailed outline of them is available as a .pdf here. They would appear to be a rich resource that deserves the detailed attention of scholars (including me, perhaps, one day, if I ever cross the Atlantic again…).

And then there has to be a note of deep regret about the fate of the Theatre 625 production of Wind Versus Polygamy. Despite it being recorded by the BBC in colour in 1968, shown again in 1970 and once more in 1971, and thus surviving for some three years, it has no presence in the archive today. The other six plays repeated for Play for Today in 1971 all exist as plays that can watched today – and tomorrow. But at some point, like so many other recordings from the 1960s and early 1970s, this drama featuring Earl Cameron and others speaking Obi Egbuna’s lines was wiped, presumably simply to save shelf space and the cost of a 2-inch videotape. A key fragment of television history and of Black culture in post-war Britain is lost forever.

I think I’m going to keep turning up little snippets of research to extend this post, and so I’ll post a selection in these Comments – while also working on the more substantial follow-up.

One intriguing note is that the production of ‘Wind Versus Polygamy’ that went to Dakar was directed by Yemi Ajibade (1929-2013), a Nigerian playwright, actor and director who from 1966 to 1968 was a friend of fellow student and later filmmaker Horace Ové at what was then the London School of Film Technique, later the London Film School.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Yemi_Ajibade

In 2004 the historian and activist Oku Ekpenyon MBE organised for a plaque to honour the great Ira Aldridge to be displayed inside the Old Vic, where he had played – https://windrushfoundation.com/community-champions/oku-ekpenyon/ . Earl Cameron attended the launch reception and when he spoke he revealed that he had had voice coaching from Ira Aldridge’s daughter. I think this must have been Amanda Aldridge – https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Amanda_Aldridge . It was a wonderful bit of lineage between generations of great actors.

Thanks, Sandy – what an extraordinary historical link.

I imagine that this might come in the second part, but it’s worth mentioning Buchi Emecheta’ s ‘A Kind Of Marriage’ – surely the only other play about Igbo culture produced for British television in the last century – as a companion piece. The thirty minute drama was produced for BBC2’s ‘Centre Play’ anthology series in 1976, directed by Mary Ridge and Anne Head. It was shown at the BFI in 2018 – you wrote an excellent post about the screening – https://www.illuminationsmedia.co.uk/tv-incognita/

Thanks, Billy – and that’s a welcome reminder (which I hadn’t intended to flag in the next post). The BBC Genome entry for ‘A Kind of Marriage’ is here:

https://genome.ch.bbc.co.uk/7725a39de63b46c99e927a1567ae3074