14th January 2026

John Wyver writes: The BFI Southbank season continues tomorrow, Thursday 15 January, with an early evening screening in NFT2 of two remarkable programmes. First is a 1970 edition of the BBC2 arts magazine series Review which features a recreation of the 30-line broadcast from 1930 of The Man with the Flower in his Mouth. The original production team are reunited forty years after the original transmission to give a unique insight into the making of early television.

Following this is Jack Rosenthal’s 1986 drama The Fools on the Hill, a loving, comic (and highly inaccurate) imagining of events at Alexandra Palace leading up to the first night of the BBC’s high definition service on 2 November 1936.

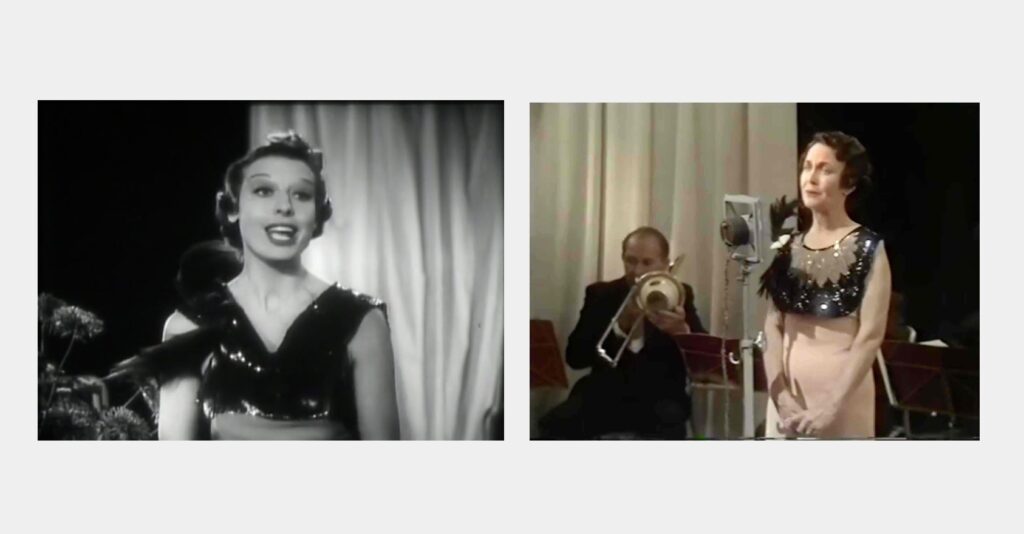

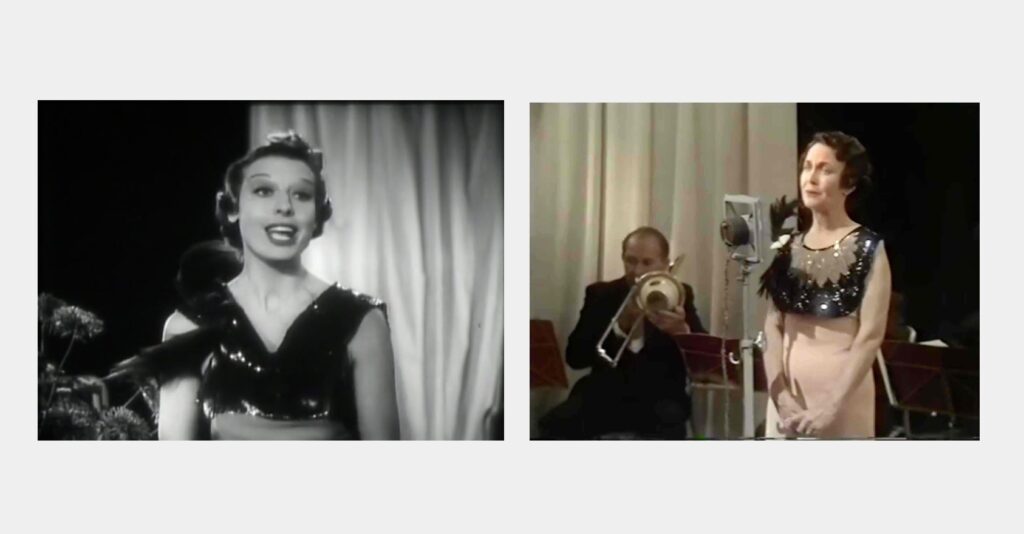

I’ll be providing an introduction and tickets are still available. Meanwhile, following is the text of the programme note that I have written for the evening. And the image above pairs Pat Whitmore as Adele Dixon from The Fools on the Hill with the real deal in Television Comes to London.

read more »

13th January 2026

John Wyver writes: Taking a break from posts about Magic Rays of Light, I am delighted to highlight another article of mine that has just been published in the latest edition of VIEW: Journal of European Television and Culture.

Online and fully open access, issue no 28 collects a rich group of exceptional contributions under the title, ‘With and Against the Grain: Creative Dialogues with Broadcast Archives’. And my essay, which is illustrated with a couple of archive extracts and a number of framegrabs, revisits the 2021 film Coventry Cathedral: Building for a New Britain that I made for BBC Four with Todd MacDonald, Ian Cross and Helen Wheatley.

read more »

12th January 2026

John Wyver writes: Tonight in the Reuben Library at BFI Southbank, I am in conversation with BFI Television Curator Lisa Kerrigan talking about, of course, Magic Rays of Light: The Early Years of British Television, which was published on Thursday. There are still a few tickets left.

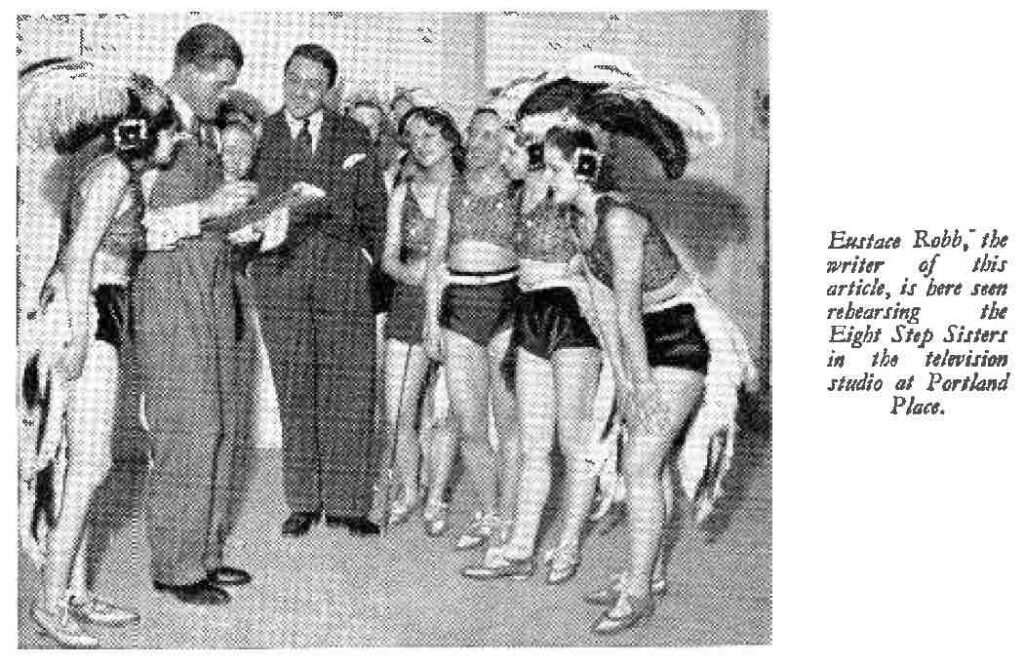

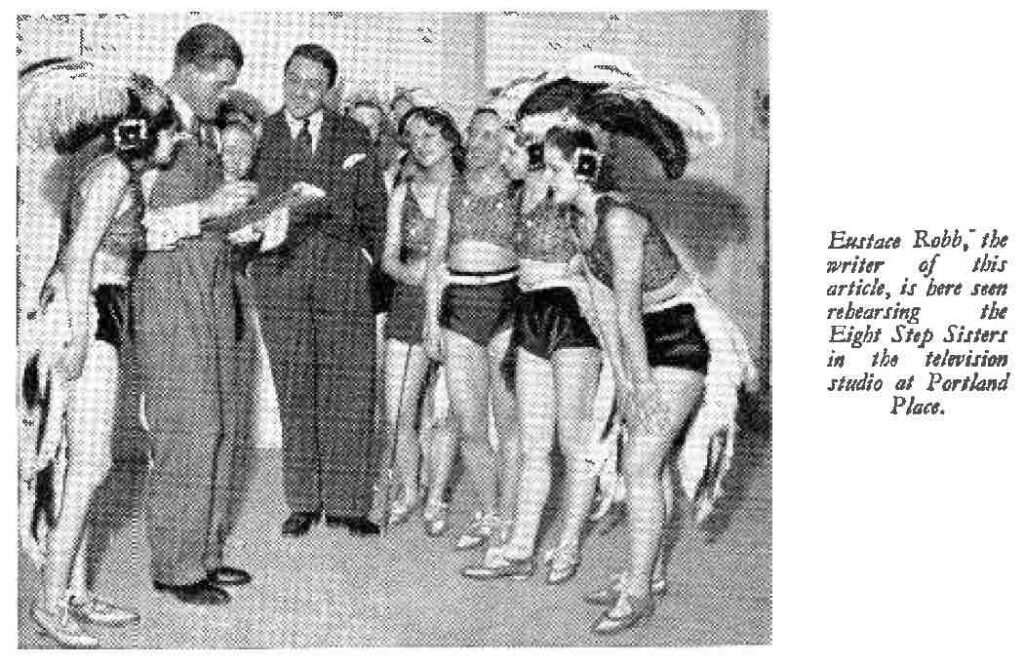

In all of the blog posts I have been contributing about this, I have not yet shared the central arguments of the book, and it is these that I outline here in this extract from the Introduction. Also briefly noted are two of the key characters in the book, critic Grace Wyndham Goldie and 30-line producer Eustace Robb (above). I spend most of the time on the book’s first proposition, and will return to the other four in future posts.

read more »

11th January 2026

John Wyver writes: too much politics today perhaps, but it’s been that kind of a week; otherwise there are a couple of great film links and a terrific AI essay, along with other articles well worth your time. This week’s image is Fernard Léger’s great 1937 mural Le Transport des Forces, which I admired greatly at the Fernand Léger National Museum at Biot this past summer.

• Film Studios in Britain, France, Germany and Italy – Architecture, Innovation, Labour, Politics, 1930-60s: in addition to my Magic Rays of Light, on Thursday Bloomsbury published this substantial and exceptional volume edited by Sarah Street and six other scholars; thrillingly – thanks to funding from the European Research Council – it’s entirely free to download.

• Talking about Wajda…: Michael Brooke’s Substack postings about central and eastern European cinema are already proving to be essential, so do subscribe; this one is especially good, about his experience in creating commentary tracks for Andrzej Wajda’s The War Trilogy; note also that BFI Southbank has a major Wajda retrospective next month.

read more »

8th January 2026

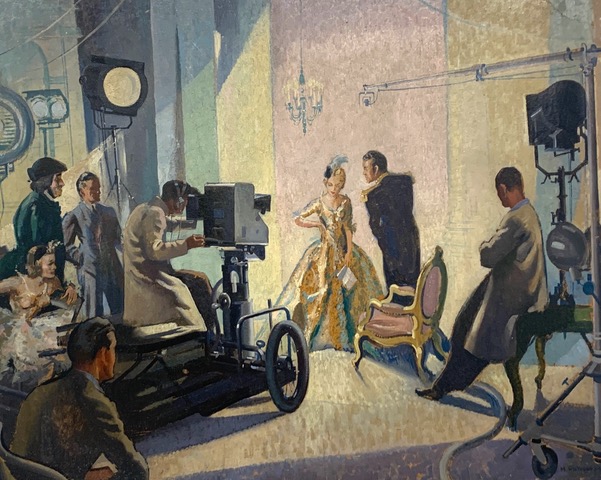

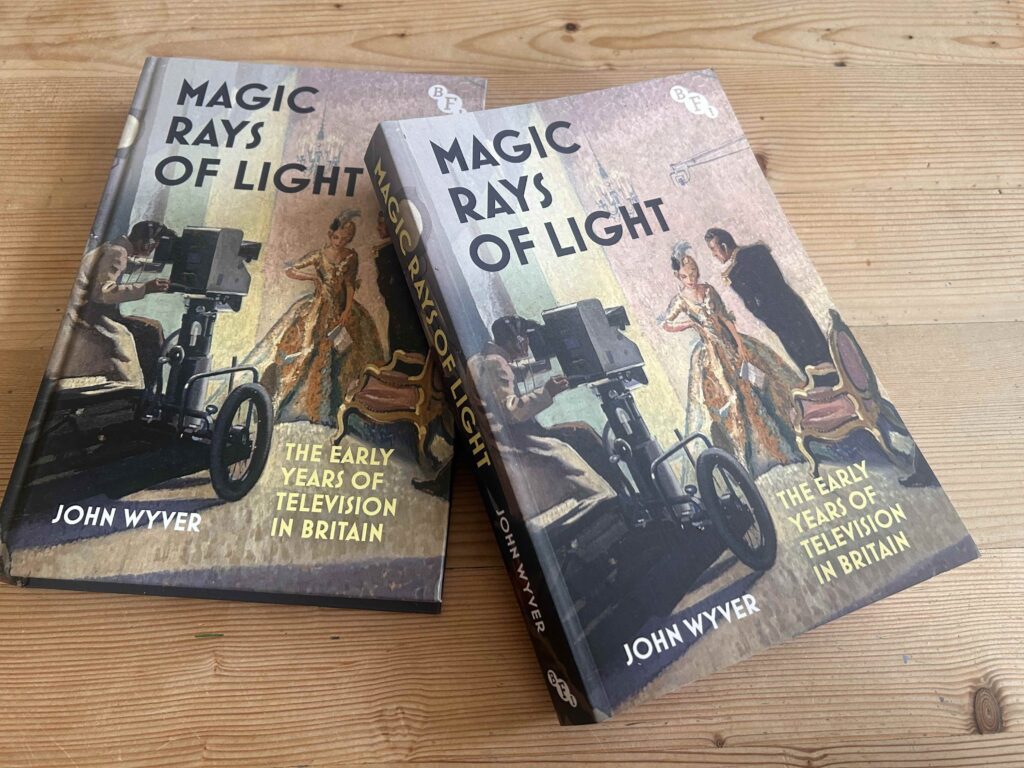

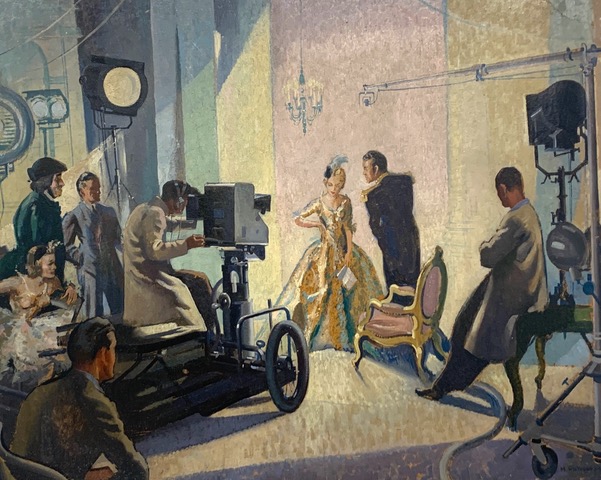

John Wyver writes: Publication day! And just in time, my copies of Magic Rays of Light: The Early Years of Television in Britain arrived yesterday. Unsurprisingly perhaps, I am thrilled. The book feels substantial but not (I hope) intimidating; the photographs have reproduced well; I really like the lay-out, the font and the weight of the paper; and the cover, with a detail of Harry Rutherford’s Starlight, 1937, looks gorgeous.

Tonight we start a season of screenings at BFI Southbank, and on Monday evening in the BFI Reuben Library I am discussing the book with Television Curator Lisa Kerrigan; there are still some tickets available. Today, in part because this is the kind of information that is rarely made public, I thought I would sketch what it has cost me to get to this point.

read more »

7th January 2026

John Wyver writes: The Magic Rays of Light season at BFI Southbank kicks off tomorrow night, Thursday 8, with a programme of four documentaries made for the early television service. On what is also publication day for the book (and when I might finally see a copy), I am introducing the programme and have written the accompanying notes, which I thought, despite it making for a long post, it might be interesting to reproduce here.

If you fancy coming there are still tickets, and you’ll see the muffin man above from Picture Page as well as much, much more, but at the time of writing the website is showing only 9 seats available.

read more »

6th January 2026

John Wyver writes: Just ahead of the publication of Magic Rays of Light on Thursday, and the accompanying BFI Southbank season that starts the same day, I am delighted to share the first news of an international conference, The Cultures of Early Television, to be held at the University of Westminster in July.

With the invaluable support of the British Academy Conference scheme, this two-day conference on 2 and 3 July in central London is intended to initiate a transnational dialogue about television in the years before World War Two.

Marking the centenary later this month of the first public presentation of what John Logie Baird called ‘true television’, the event will explore the imaginaries and achievements of the first years of the medium.

With contributions from a range of distinguished speakers from here and abroad, the programme will feature presentations, discussions and screenings addressed to early television in Britain, the United States, Europe and the Soviet Union.

More news will be made available here, and registration, which is free, will open in the early spring. But to express your interest, e-mail me at [email protected], and I will mail you back when further details are confirmed.

Header image: Starlight, 1937 by Harry Rutherford, a detail of which graces the cover of Magic Rays of Light. The painting, which hangs in the Reading Room of the BBC Written Archives Centre, is of a studio scene at the BBC Television Station at Alexandra Palace; © Estate of Harry Rutherford.

4th January 2026

John Wyver writes: My weekly round-up of stuff that has engaged me over the past seven days begins with a selection with rather less film and television than usual, although both feature, and a perhaps more eclectic range including the Bayeux Tapestry, AI and cricket. Some great music too.

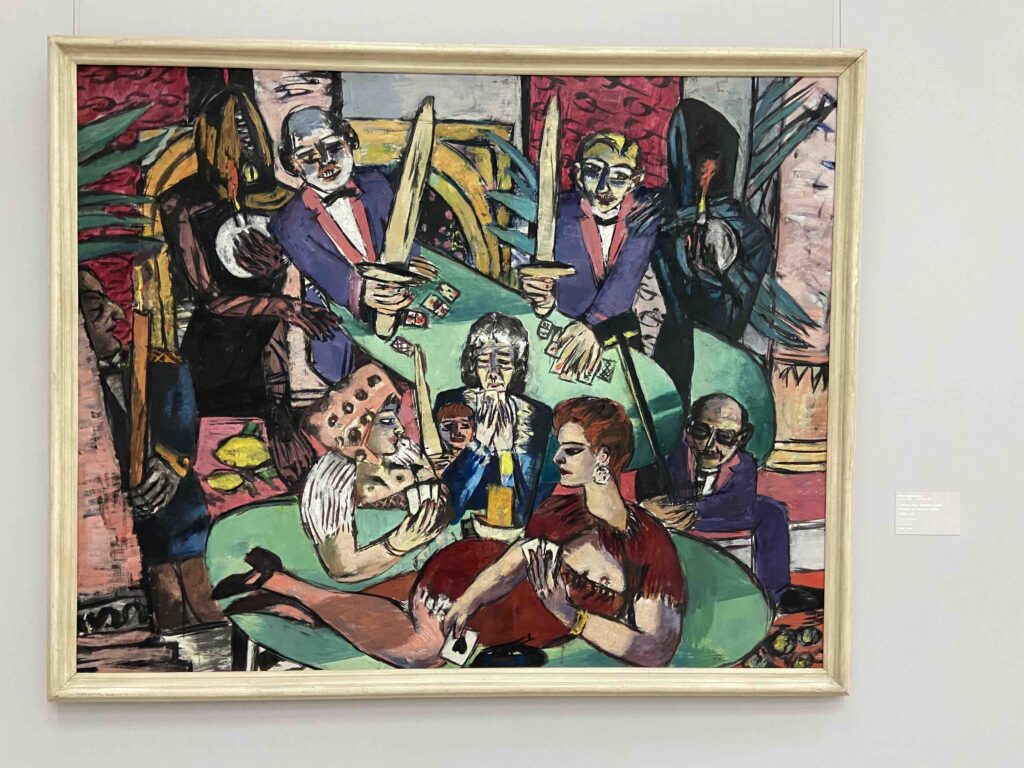

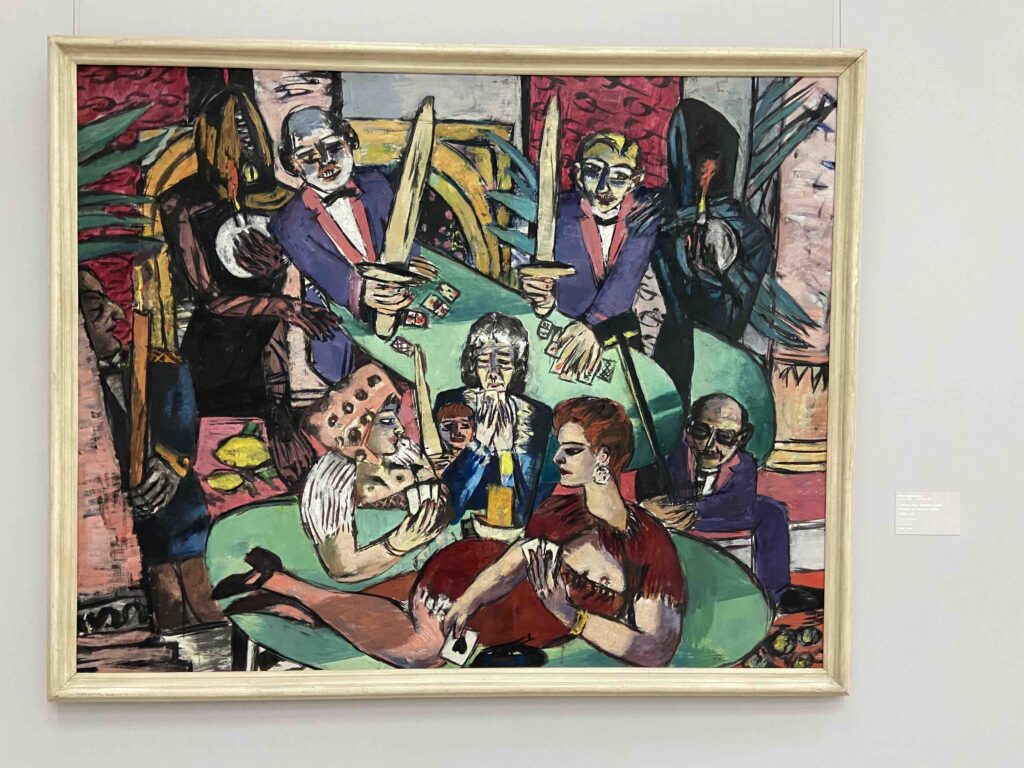

This week’s image above is Max Beckmann’s Dream of Monte Carlo, 1939-43, which I marvelled at in the Neue Stattsgalerie Stuttgart last summer.

• Introduction: I really appreciated critic Michael Brooke’s tale of his journey into central and eastern European film, and the importance of BBC2 and Channel 4 to this, which he posted this week by way of trailing his series of (very) regular posts on the topic, which I am already enjoying; click on the link to find out how to subscribe.

• about that December 28th anniversary: for anyone with an interest in early cinema, Dan Streible’s richly illustrated revisionist reflection on the first commercial, public screening of cinematographic films is a goldmine.

• Soderblog – Seen, Read 2025: filmmaker Steven Soderbergh produces one of the very best end-of-year-lists in his distinctive record of all that he has watched and read during the year, complete with the dates when he did so (along with occasional notes about scripts and filming).

read more »

2nd January 2026

John Wyver writes: With the new year upon us, and with less than a week to go before the first screening, I thought it might be a moment to look at the sales for the BFI Magic Rays of Light Season. As you’ll know, this is linked to next week’s publication of Magic Rays of Light: The Early Years of Television in Britain as a Bloomsbury/BFI hardback, paperback and e-book (all available at a discount via the link from the publisher).

We are screening a number of pre-war documentaries made for the high definition television service from Alexandra Palace, a delightful Jack Rosenthal drama about the service from there, and a selection of rarely-seen feature films from the early 1930s that in different ways imagine how television will be realised (including High Treason, 1929, above).

read more »

30th December 2025

John Wyver writes: Welcome to an eclectic year-end list of the books, exhibitions, films, performances and other stuff (although not much music) that enhanced and enriched my 2025. There are some obvious choices here, but for the most part I have tended towards the perhaps-surprising or marginal or over-looked. The listing in neither a chronology nor a ranking.

Taken together they offer a sense of (some of) what engaged and enthused me during a year when the genocide in Gaza and the trashing of democracy in the States and the war in Ukraine and the disappointments of Labour here, along with all the rest of the hideousness, pressed in upon us in sometimes near-intolerable ways. Essentially a retrospect of responses, there is also an idea or two for viewing or reading or visiting in the new year. And why 54? Why not? Warm best wishes for a better 2026.

As for the painting above, it is Harry Kingsley’s New Street, 1956, in the collection of Manchester Art Gallery…

• Manchester Art Gallery: having almost all of a day free in Manchester in the spring, I decided to spend it with the permanent collection in Whitworth Street, and it was such a pleasure; I devoted extended time to a few works (Stubbs, Valette, Sickert, Wadsworth), and I appreciated the gallery’s focus on its audiences, on context and displays like What is Manchester Art Gallery?, and on concerns about race, empire and decolonisation – I really liked the café too.

• Headingley Test against India: the last few weeks have been desperately dispiriting for any fan of the England cricket team, so it’s worth recalling the glorious chase in June to reach the target of 371 in the final hour.

read more »