25th July 2025

John Wyver writes: Under the headline ‘Film workers & television: wide effect on entertainment’, the Daily Telegraph on 25 July 1939 carried a fascinating report of a speech made the previous day by Robert Finnigan as the presidential; address to the annual conference in London of the National Association of Theatrical and Kiné Employees. As the paper’s industrial correspondent noted, ‘The conference represents many thousands of workers in all departments of the film trade.’

The paper summed up the speech’s theme as follows:

The Luddites – bands of mechanics who organised riots in 1811-16 – smashed machinery. The modern worker should adapt himself to innovations and co-operate with the employers.

Finnigan was concerned with the development of television and its impact on the film industry, and he announced that the conference would adjourn the following day to see a television demonstration in a West End cinema and hear a technical explanation.

read more »

24th July 2025

John Wyver writes: The evening schedule of Sunday 24 July 1938 was occupied by Shakespeare’s The Tragedy of Julius Caesar (billed under its full name) given in modern dress by a strong company under the direction of the invariably innovative Dallas Bower. Ernest Milton was Caesar and D.A. Clarke-Smith Marcus Antonius, while Sebastian Shaw took the role of Brutus and Anthony Ireland, Cassius. Laura Cowie played Calpurnia, and Carol Goodner, Portia.

Bower set the political drama in an unidentified European state which observers were encouraged to see as a fascist regime. He also worked with designers Peter Bax and Malcolm Baker-Smith to use for the first time their ‘penumbrascope’, which threw abstracted patterns on a cyclorama to suggest a range of settings including cityscapes. In addition, he integrated a number of newsreel scenes, listed as ‘riots’, ‘gunfire’, explosions’ and ‘aeroplanes’.

read more »

23rd July 2025

John Wyver writes: The line-up for the Baird Television transmission at 11am on the morning of Wednesday 23 July 1930 featured, as usual, a trio of entertainers. Scottish (although billed as ‘Scotch’) music hall comedian Tommy Lorne was up first, then baritone Frederick Yule, later to be an ITMA cast member during the war, followed by soprano Elsie Otley.

Each contributed an approximately 10-minute turn, standing in the scanner’s beam in a blacked-out studio so that their head and shoulders, along with their voice, were reproduced on a few hundred tiny, portrait-formatted 30-line screens across the country.

The Covent Garden studio at the time was transmitting a half-hour each weekday morning, along with an additional Friday half-hour at midnight. Broadcasts of this kind, with an occasional OB or drama like The Man with the Flower in his Mouth the previous week, had been offered with synchronous sound and vision for nearly four months now. They would continue until 1 July 1932, after which the BBC took over responsibility.

read more »

22nd July 2025

John Wyver writes: ‘Crisis in television’ was, as you can see, the The Era‘s timeless headline on its weekly edition datelined Thursday 22 July 1937. Nine months after the start of the BBC’s ‘high definition’ service from Alexandra Palace, the well-informed correspondent Kenneth Baily was warning that,

To avoid a first-class broadcasting crisis in this country the Government must quickly decide who is to foot the bill for Television development on a national basis.

The crux of the issue, as ever, was finance.

read more »

21st July 2025

John Wyver writes: Wednesday 21 July 1937 fell in the middle of the last week when the Radio Times Television Supplement was published in the London edition of the listings magazine. At the centre of three pages of detailed programme details was the schedule (below) that promised cartoonist Ernest Mills, a ‘local OB’ of children playing in Alexandra Park (which would be cancelled because of rain), The Dancers of Don, a newsreel, a revue titled Ad Lib, and in the evening singer Marie Eve, and a nautical revue that would become a regular favourite, The Mizzen Cross Trees.

read more »

20th July 2025

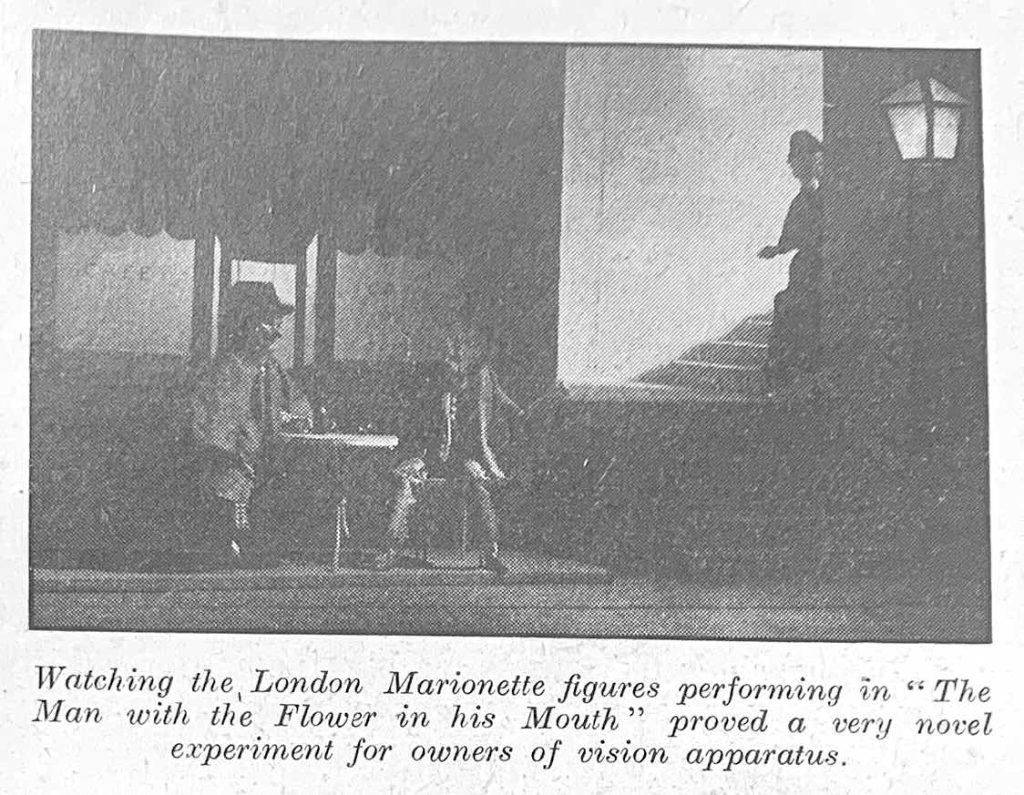

John Wyver writes: On the afternoon of 20 July 1937 the BBC television service mounted a new presentation of Luigi Pirandello‘s oblique modernist dialogue The Man with the Flower in his Mouth. Just over seven years before, as we saw in a recent blog post, this one-act drama had been produced by Lance Sieveking for Baird company. Now Jan Bussell was the producer, working with a cast of William Devlin, Philip Thornley and Genitha Halsey.

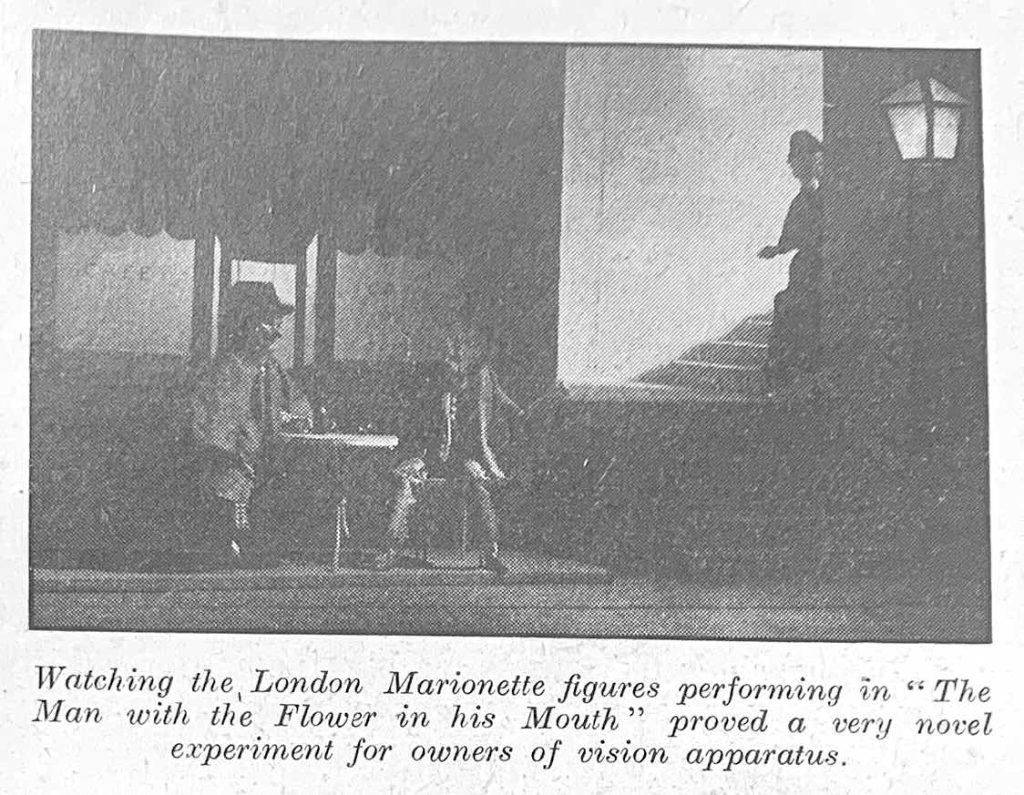

Beyond its sinple staging requirements, the popularity of the Pirandello is hard to account for, especially when we also factor in a third production, like the first for the 30-line service, and also produced by Bussell, but in this case with marionettes (above).

Working with his life partner Ann Hogarth, who was later to give the world Muffin the Mule, Bussell gave The Man… on the morning of Thursday 2 April 1931, when 30-line transmissions were still being produced by the Baird company. As the rare photograph from Television shows, Bussell and Hogarth conjured up a noir-inflected setting for this eccentric puppet Pirandello.

[OTD post no. 215; part of a long-running series leading up to the publication of my book Magic Rays of Light: The Early Years of Television in Britain in January 2026.]

19th July 2025

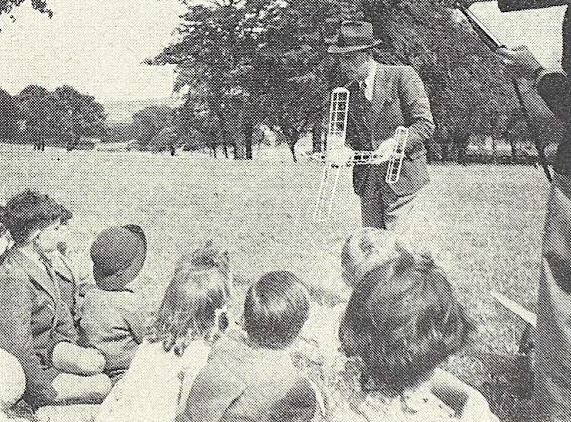

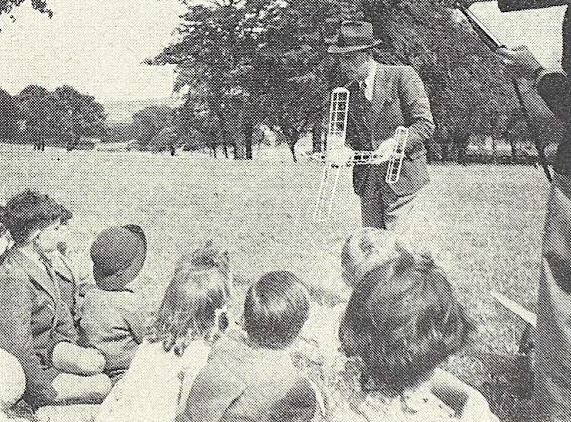

John Wyver writes: More or less from the start of the Alexandra Palace operation viewers wanted director of television Gerald Cock to schedule a regular slot for youngsters. Cock pleaded shortage of resources and airtime, but eventually offered up a first clutch of programmes on the afternoon of Wednesday 19 July 1939.

The Daily Telegraph‘s correspondent the next day declared it ‘an hilarious success’.

Twenty children of BBC employees formed an audience in the studio. and also unknowingly provided part of the entertainment. A camera concealed from them showed pictures of the youngsters, from time to time, intent on the stage and rocking with laughter.

Delightfully, Grace Wyndham Goldie’s verdict was considerably more circumspect:

Television doesn’t yet provide a Children’s Hour. But there crept into last week’s programmes the first of a series which is coyly described as being ‘for the younger viewer’. Now this is important. For the Children’s Hour is one of the triumphant successes of sound broadcasting and the first steps towards a television Children’s Hour are worth watching.

read more »

18th July 2025

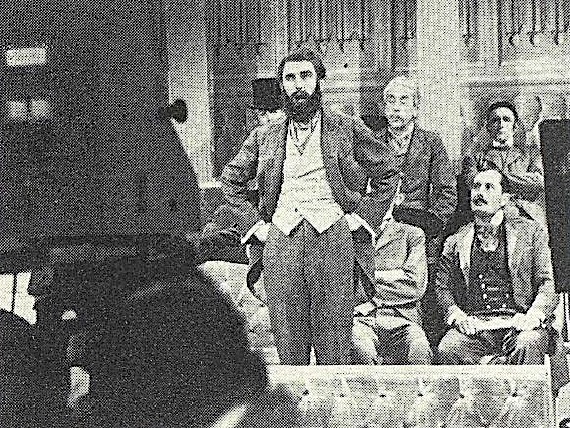

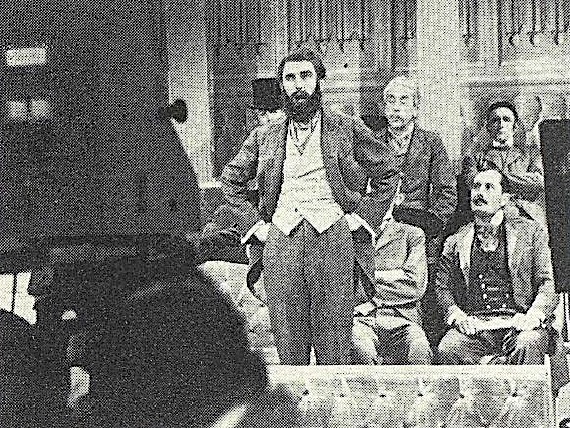

John Wyver writes: On the evening of Tuesday 18 July 1939 Irish playwright and producer Denis Johnston presented The Parnell Commission (above), a reconstruction of the forgery investigation of 1888-89. Johnston had made this as a radio feature some months before, and now he brought together a large cast to act out the judicial inquiry into allegations of crimes by Irish parliamentarian Charles Stewart Parnell which resulted in his vindication.

‘The Scanner’ in Radio Times trailed the transmission in this way:

[A]ll the principal characters… will be made as real to life as possible by being modelled on contemporary Spy cartoons and pictures in the Illustrated London News. You will thus be deprived of Clark Gable, but you will see Parnell with a beard, more or less as he was when The Times printed a letter in 1887 implicating him in the Phcenix Park murders.

Here then is the beginning of the form that would later become identified as ‘drama documentary’.

read more »

17th July 2025

John Wyver writes: The evening of Monday 17 July 1939 saw one of the BBC’s two mobile control rooms back at the Victoria Palace Theatre for a reprise OB of the musical Me and My Girl, first broadcast on 1 May and subject of an earlier blog post. The transmission came at the end of a week in which there had been a major drama each day, indicating how ambitious the Alexandra Palace schedule now was.

Tuesday 11 saw the second playing of a studio staging of Michael Barringer’s mystery play Inquest which had premiered at the Windmill Theatre in 1931. This had been made into a film in the year it was first played, and it appeared again as an hour long ‘quota quickie’ movie, this time directed by Roy Boulting, in December 1939. At AP an 80-minute adaptation, produced by Lanham Titchener, had former silent movie star Mary Glynne and Herbert Lom as the leads, and Lom again took the role of the Coroner in Boulting’s film.

read more »

16th July 2025

John Wyver writes: Noting ‘E.H.R.’s brief review in The Observer on Sunday 16 July 1939 of East End, a programme that was broadcast four days before, allows me both to preserve OTD-ness today while at the same time writing about a really interesting programme that I would have otherwise missed.

Of East End, the critic wrote that it was

an exploration of London’s slums and industrial areas, of which most of us know very little. It was a real gain to knowledge.

East End was a kind of follow-up to Soho, a ‘documentary’ made in the Alexandra Palace studio about which I wrote in April. Producer Andrew Miller Jones and journalist S.E. Reynolds made another attempt at bringing to AP characters from an area of London and presenting them, along with brief film sequences, in a succession of studio settings, a number of which were suggested visually by the penumbrascope. Silk weavers, upholsterers and other inhabitants were interviewed by Mass-Observation co-founder and polymath Tom Harrisson, who we have also met before in this blog.

read more »